GeographyCaseStudy.Com

Detailed resources for pre-university Geography students

Case study: Ecotourism in Kenya

By Matt Burdett, 27 January 2018

On this page, we look at ecotourism in Kenya as one case study of sustainable tourism in one low-income country.

Ecotourism in Kenya

Kenya has a wide range of ecotourism activities, including cultural (indigenous peoples) and environmental (hiking and adventure tourism, and wildlife safaris). For example (Kenya Travel Tips, 2018):

- About 7.5% of the country is designated for wildlife conservation

- There are 23 National Parks and 28 National Reserves, plus six marine reserves

- Wide range of wildlife including lions, elephants, zebras and over 1070 bird species

- 536 kilometers of coastline, which is largely sandy beaches

- Six World Heritage Sites

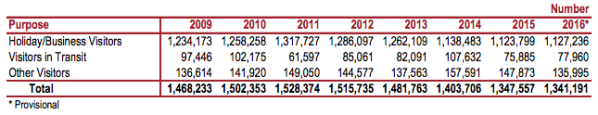

Tourism is a major industry in Kenya. However, it is very difficult to ascertain detailed figures on ecotourism, although there are some figures about tourism in general. The Kenya National Bureau of Statistics collects detailed information about tourism. The number of international visitors has been largely stable for several years there has been a slight decrease:

- Reported Visitor Departures by Purpose, 2009 – 2016. Source: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2017.

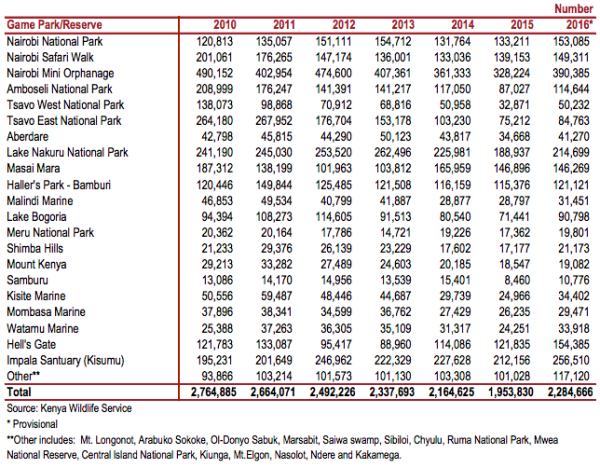

The number of tourists visiting the Game Parks and National Reserves actually decreased during the same period, as shown below. This corresponds with the slight decrease in overall holiday visitors during the same period, but it is not evenly distributed among the parks with some, such as the Nairobi National Park, experiencing an increase.

These visitors contribute an estimated US$1 billion per year to the Kenyan economy, which is roughly 10% of gross domestic product. Tourism is the biggest industry in Kenya, employing 9.3% of workers (Kenya Tourism Board, 2016).

National scale ecotourism

Responsibility for tourism in Kenya is under the Kenya Tourist Board. It has a sustainability committee which works on four principles (Kenya Tourism Board, 2016):

- Environmental conservation

- Education and empowerment

- Social responsibility

- Culture and heritage preservation

The Kenya Tourist Board introduced an ‘Eco-rating Scheme’ in 2002 for accommodation providers (such as hotels) and in 2015 this was expanded to tour operators with the ‘Travel Life’ rating scheme. There are now over 100 eco-rated facilities in Kenya. There are also annual awards given for the most sustainable practices.

These advances are in line with Vision 2030, Kenya’s national development plan. Tourism is the lead sector in the plan to achieve a transformation of the national economy (Kenya Tourism Board, 2016).

Kenya’s plans for tourism rely on five pillars to avoid greenwashing . ‘Greenwashing’ is a term “used to describe the act of misleading consumers regarding the environmental practices of a company or the environmental benefits of a product or service” (Greenpeace, n.d.). The five pillars are:

- Pillar 1 – Leveraging the Might of Giants / Benchmarking. This means that Kenya looks abroad at similar policies to learn lessons, such as looking at Ecotourism Australia, and CAST in the Caribbean

- Pillar 2 – Broad & Inclusive Sustainability Guidelines. Reference to the Sustainable Development Goals.

- Pillar 3 – Education & Specialization. Includes support for three major tourism conferences held annually in Kenya.

- Pillar 4 – Recognition of Champions. Eco-rating Schemes and other awards.

- Pillar 5- Partnership / Integration. Includes stakeholder agreement and recognition.

Local scale sustainable tourism: The Maasai Mara National Reserve

- Maasai Mara National Reserve, Kenya. Source: Key45, 2003.

The Maasai Mara National Reserve was first established in 1961. Since then it has earned a reputation as one of the best ecotourism destinations in the world. Ecotourism is encouraged by tour companies and accommodation providers.

Cottars Safari Service

Cottars is one of the oldest tourism companies in Kenya, having been first registered in 1919. It is an award winning ecotourism company that makes efforts to be sustainable. It operates in the area around the Maasai Mara National Reserve.

- When visitors come to the area and use Cottars, they are expressly charged a lease fee for wildlife conservation. Some of this revenue is shared with local communities and also used to help develop the 6,000 acre Olderikesi Wildlife Conservancy on the edge of the Reserve as a way to expand the area under conservation.

- Cottars employs accredited guides to ensure they are in harmony with the environment and culture of the area; many of these guides are from the local area.

- Tourists are encouraged to bring a few items with them from their home country that can support local people, such as school supplies for the Olpalagilagi Primary School for a total of 200 students.

- Cottars takes tourists to visit the local Maasai villages which helps to provide a market for traditional products such as beads, which helps local people economically.

- Financial and legal support was provided to local communities to fight for land rights, resulting in the legal ownership of the Olderkesi Group Ranch in 2010.

- Combines with groups such as Bridging the Gap; a bridge was built across the Sand River, preventing an average of six deaths per year and allowing local people to access social amenities.

(Sources: Cottars, 2015; Cottars.com, 2012)

Olarro Lodge

- Olarro Lodge, Kenya. Source: Sunsafaris.com

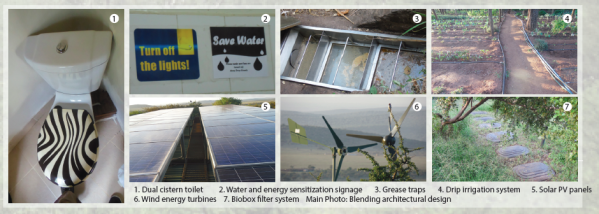

Olarro Lodge is a rural hotel about halfway between Nairobi and Lake Victoria, near the border with Tanzania. In January 2015, it won the coveted Gold Eco-rating Certification from Ecotourism Kenya. It is about 5 km from the Maasai Mara nature reserve, and is within the Olarro Conservancy. The conservancy is a 7,500 acre area which is owned by around 150 local Maasai landowners. To ensure the principles of ecotourism are successfully implemented, the Lodge has made several alterations to be more sustainable.

- Solar power is produced on-site with 150 solar panels

- Two wind turbines add to the electrical supply

- Water is heated with 17 solar water heaters, which can heat around 600 liters of water each

- Signage encourages visitors to save electricity

- Energy saving light bulbs are found throughout the hotel

- Water is sourced from a natural spring within the conservancy, and rainwater is harvested from rooftops of the buildings and stored in three 100,000 litre underground tanks

- Waste water is treated on-site and used to provide irrigation for the hotel’s lawns

- Guests are encouraged to behave more sustainably by being educated about these features on their arrival

- Olarro Lodge, Kenya. Source: Karanja and Shabanji, 2015.

Cottars, C., 2015. Cottars Strive for Excellence in Sustainable Tourism. In Naturals Magazine number 06. https://ecotourismkenya.org/resource-centre/downloads/#toggle-id-7 Accessed 27 January 2018.

Cottars.com, 2012. Cottar’s Conservation, Community, Culture & Commerce. http://www.cottars.com/conservation-community Accessed 27 January 2018.

Greenpeace, n.d. Greenwashing. https://stopgreenwash.org/history Accessed 27 January 2018.

Karanja and Shabanji, 2015. Replicable Best Practices At Olarro Lodge. In Naturals Magazine number 06. https://ecotourismkenya.org/resource-centre/downloads/#toggle-id-7 Accessed 27 January 2018.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2017. Statistical Abstract 2017. https://www.knbs.or.ke/publications/ Accessed 27 January 2018.

Kenya Tourism Board, 2016. Sustainable Tourism Report 2016 http://ktb.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/KTB-Sustainable-Tourism-Report-2016.pdf Accessed 27 January 2018.

Kenya Travel Tips, 2018. Tourism in Kenya. https://www.kenyatraveltips.com/tourism-in-kenya/ Accessed 27 January 2018.

Key45, 2003. Gnus and zebras in the Maasai Mara park reserve in Kenya. Wildebeest and zebra migration in Maasai Mara. Sourced from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GnusAndZebrasInMaraMaasai.jpg Accessed 27 January 2018.

Sunsafaris.com, n.d. https://www.sunsafaris.com/safari/kenya/Maasai-mara/olarro-lodge.html Accessed 27 January 2018.

Case study: Ecotourism in Kenya: Learning activities

- Why is Kenya a suitable destination for ecotourism? [4]

- Outline the changes in tourism numbers in Kenya in recent years. [3]

- Outline the national approach taken to ecotourism in Kenya. [5]

- Suggest how the Maasai Mara National Reserve can be considered in keeping with ecotourism principles. [6]

- Do you consider tourists to the Olarro Lodge are ecotourists? Explain your answer. [4]

- Overall, do you think ecotourism can bring benefits to people in Kenya? Why? [8]

Other tasks

Conduct research into another remote tourist destination that offers ecotourism, such as the Kuna Yala of Panama. Compare the efforts made by both destinations and suggest which is the more sustainable form of ecotourism.

Share this:

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, promoting sustainable festival events tourism: a case study of lamu kenya.

Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes

ISSN : 1755-4217

Article publication date: 14 June 2011

Tourism has been a key force in promoting festival growth and expansion. Towns, villages and cities are increasingly keen to share their culture, environment and spending opportunities with visitors by the promotion of festivals. One such festival is held annually in Lamu Old Town, a world heritage site in Kenya. The purpose of the paper is to highlight the importance of hosting sustainable events in Kenya.

Design/methodology/approach

The subject scope is on maintaining sustainable events within local communities with an aim of improving the local economy.

Results suggest that although festivals may have the potential to provide opportunities for sustainable local economic development, such opportunities frequently remain unexploited. For these reasons, festivals' engagement with tourism forces in Lamu need to be carefully managed, both in the interests of sustaining festivals and of promoting sustainable approaches to tourism development.

Practical implications

In addition to their cultural and social values, cultural festivals have emerged as an instrument for tourism development, tourism seasonality expansion, city image improvement and boosting regional economies. Therefore, the implications will be to invest in festivals development and community engagement and present the tourist with authentic experiences.

Originality/value

This article is valuable to policy makers as not enough research has been done on the importance of this festival and the need to provide a significant role to the local people in Lamu in communicating their identity, history and cultural practices.

- Sustainability

- Sustainable development

Okech, R.N. (2011), "Promoting sustainable festival events tourism: a case study of Lamu Kenya", Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes , Vol. 3 No. 3, pp. 193-202. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554211111142158

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2011, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

- Programmes Consumer Information for SCP Sustainable Buildings and Construction Sustainable Food Systems Sustainable Lifestyles & Education Sustainable Public Procurement Sustainable Tourism

- Network Members Directory Organisations

Case Study Ecotourism Kenya - Guidelines for Providing Product Sustainability Information

- Published on July 1, 2019

Actors involved:

Programme(s):, share your work on sustainable consumption and production, you might also be interested in.

Communicating Product Sustainability Information related to Chemicals

Consumer information for scp.

Consumer Information Online Conference: Turning Information Into Action

Sustainable tourism, sustainable buildings and construction, sustainable lifestyles & education, sustainable public procurement, sustainable food systems.

Consumer Information online conference - TURNING INFORMATION INTO ACTION

Select a language.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Suistainability in Kenya's Tourism

Related Papers

Annals of Tourism Research

Peter Dieke

Harold Goodwin

Patrick Mamimine

Human activities are damaging world heritage sites threatening sustainable tourism development. The study explored the extent to which human activities are affecting sustainable tourism development at cultural heritage sites the case of Great Zimbabwe. Quantitative data was collected using a questionnaire following convenient sampling technique. Using means, standard deviation and variance, results reveal that there are 16 human activities that are affecting sustainable tourism development. Upon factoring 7 factors emerged which are pollution, societal crime and conflict, defacing, hunting, landscape degradation, vandalism and environmental pressure. A linear regression model reveals that human activities are negatively affecting sustainable tourism development at heritage sites with 4 factors significant at p<0.1. However, human factors only explain 14% (Adjusted R 2 =0.14) of sustainability problems at heritage sites. The study concluded that human activities are in indeed affe...

Tourism Policy, Planning at National, Regional and Local Level (based on slides by Dr. Johan Afendi bin Ibrahim)

Journal of Tourism & Hospitality

Moses Okello

Pacific Journal of Science and Technology. 15(1):458-483

Medani Bhandari

Cavagnaro, E., Staffieri, S and Ngesa, F. (2015). Looking from a local lens: Inbound tour operators and sustainable tourism in Kenya, Research in Hospitality Management, 5(2) pp.135-145

Elena Cavagnaro

Few empirical studies on sustainable tourism take into account the perspective of developing countries’ actors. This is even the case in debates about the need to adapt sustainability’s definitions to the context of developing countries. The present study aims at giving a voice to developing countries’ actors by describing how inbound tour operators (ITOs) in Kenya conceive sustainable tourism and their role in promoting it. ITOs were reached through the two official Kenyan category associations for tour operators and through Ecotourism Kenya. Both a survey and in-depth interviews were used to gather data. Results suggest that Kenyan ITOs are familiar with the current definition of sustainability as being constituted of an economic, a social and an environmental dimension. Contrary to expectations, respondents weight their responsibility towards the natural environment at least as highly as their social responsibility. In the end, it is the business long-term survival that dictates this choice: respondents are aware that tourists expect to find in Kenya a flourishing natural environment. Kenyan ITOs are on the whole keenly aware of their role in promoting sustainability to tourist, staff and the community. They experience as a major challenge the lack of institutional pressure from the government. Though this is a common complaint of organisations in developing countries, it is interesting in a Kenyan context where the Government has deployed several policy initiatives on sustainable tourism. A major limitation of this study is the limited sample. Only category associations’ members were sampled, leaving ITOs that operate in the informal economy unheard.

Kent akademisi

Elif GÜNDÜZ

Tourism Management Perspectives

Haushila Prasad

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Adina Filip

Contemporary Tourism Reviews

Recent Trends in Management and Commerce

Sathiyaraj Chinnasamy , Manjula Selvam , Sowmiya Soundharaj

Maximiliano E. Korstanje

Md. Betab Hossen

Joseph Mwaniki

Tourism Planning & Development

Fuchaka Waswa

Routledge Journals, Taylor and Francis

Kate Rivett-Carnac

Journal of Leisure Research

Mike Ellerbrock

Vilson Barroso Magalhães

Dynamiques environnementales

bernard Calas

Ralf C Buckley

Alline Storni

C. Michael Hall

Yidnekachew Habtamu

Jarkko Saarinen

Díaz, P. (Ed.). 2014. Tourism as a Tool for Development. Southampton, UK & Billerica, USA: WIT Press.

Pablo Díaz Rodríguez

Tourism Review

Steven Pike

Ashraf Al Deen

Gudeta Bilisa

Mugadu Yairo

Joesef Karim

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Tourism and socio-economic development in developing countries: A case study of Mombasa Resort in Kenya

| Type | Journal Article - Journal of sustainable tourism |

| Title | Tourism and socio-economic development in developing countries: A case study of Mombasa Resort in Kenya |

| Author(s) | |

| Volume | 15 |

| Issue | 6 |

| Publication (Day/Month/Year) | 2007 |

| Page numbers | 735-748 |

| URL | |

| Abstract |

| » |

- UoN Digital Repository Home

- Theses and Dissertations

- Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, Law, Business Mgt (FoA&SS / FoL / FBM)

The Role of “mice” Tourism in Promoting Sustainable Development in Africa: a Case Study of Kenya

Usage rights, collections.

- Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences, Law, Business Mgt (FoA&SS / FoL / FBM) [24486]

The following license files are associated with this item:

- Creative Commons

Tourism Case Study: Kenya

Tourism in kenya.

Kenya is in East Africa. In 2000, its GNI per capita was $800. In 2019, it was $1,200. Kenya used tourism to help grow it to develop.

How did the Kenyan government boost tourism?

- The Kenya Tourist Board created a website and campaign called 'Magical Kenya', which advertises Kenya's beaches, safari parks, golf, and white water rafting internationlly.

- In 2009, the Kenyan Minister for Tourism halved visa fees for adults and removed them for children.

Advantages of Kenya's growth in tourism

- Tourism is now 15% of Kenya's exports and has created 1.1 million jobs in Kenya.

- Tourism is worth 8.8% of Kenya's GNI.

- Sustainable hunting and sustainable forestry can be supported by the fees that tourists pay to enter Kenyan national parks, like the Maasai Mara National Park.

- Kenya's HDI has risen from 0.467 in 1990 to 0.579 in 2018.

Disadvantages of Kenya's growth in tourism

- Although tourism accounts for 8.8% of Kenya's GNI, this has been falling since 2015.

- Tourists' preferences can be very short-term. Investing in manufacturing is more likely to be certain and long-lasting than investing in tourism. There is almost a fashion element to people's travel preferences.

- The awareness campaigns about Kenya's wildlife may have led to increases in poaching. In 2018, the Kenyan government proposed imposing the death penalty for poachers.

1 Geography Skills

1.1 Mapping

1.1.1 Map Making

1.1.2 OS Maps

1.1.3 Grid References

1.1.4 Contour Lines

1.1.5 Symbols, Scale and Distance

1.1.6 Directions on Maps

1.1.7 Describing Routes

1.1.8 Map Projections

1.1.9 Aerial & Satellite Images

1.1.10 Using Maps to Make Decisions

1.2 Geographical Information Systems

1.2.1 Geographical Information Systems

1.2.2 How do Geographical Information Systems Work?

1.2.3 Using Geographical Information Systems

1.2.4 End of Topic Test - Geography Skills

2 Geology of the UK

2.1 The UK's Rocks

2.1.1 The UK's Main Rock Types

2.1.2 The UK's Landscape

2.1.3 Using Rocks

2.1.4 Weathering

2.2 Case Study: The Peak District

2.2.1 The Peak District

2.2.2 Limestone Landforms

2.2.3 Quarrying

3 Geography of the World

3.1 Geography of America & Europe

3.1.1 North America

3.1.2 South America

3.1.3 Europe

3.1.4 The European Union

3.1.5 The Continents

3.1.6 The Oceans

3.1.7 Longitude

3.1.8 Latitude

3.1.9 End of Topic Test - Geography of the World

4 Development

4.1 Development

4.1.1 Classifying Development

4.1.3 Evaluation of GDP

4.1.4 The Human Development Index

4.1.5 Population Structure

4.1.6 Developing Countries

4.1.7 Emerging Countries

4.1.8 Developed Countries

4.1.9 Comparing Development

4.2 Uneven Development

4.2.1 Consequences of Uneven Development

4.2.2 Physical Factors Affecting Development

4.2.3 Historic Factors Affecting Development

4.2.4 Human & Social Factors Affecting Development

4.2.5 Breaking Out of the Poverty Cycle

4.3 Case Study: Democratic Republic of Congo

4.3.1 The DRC: An Overview

4.3.2 Political & Social Factors Affecting Development

4.3.3 Environmental Factors Affecting the DRC

4.3.4 The DRC: Aid

4.3.5 The Pros & Cons of Aid in DRC

4.3.6 Top-Down vs Bottom-Up in DRC

4.3.7 The DRC: Comparison with the UK

4.3.8 The DRC: Against Malaria Foundation

4.4 Case Study: Nigeria

4.4.1 The Importance & Development of Nigeria

4.4.2 Nigeria's Relationships with the Rest of the World

4.4.3 Urban Growth in Lagos

4.4.4 Population Growth in Lagos

4.4.5 Factors influencing Nigeria's Growth

4.4.6 Nigeria: Comparison with the UK

5 Weather & Climate

5.1 Weather

5.1.1 Weather & Climate

5.1.2 Components of Weather

5.1.3 Temperature

5.1.4 Sunshine, Humidity & Air Pressure

5.1.5 Cloud Cover

5.1.6 Precipitation

5.1.7 Convectional Precipitation

5.1.8 Frontal Precipitation

5.1.9 Relief or Orographic Precipitation

5.1.10 Wind

5.1.11 Extreme Wind

5.1.12 Recording the Weather

5.1.13 Extreme Weather

5.2 Climate

5.2.1 Climate of the British Isles

5.2.2 Comparing Weather & Climate London

5.2.3 Climate of the Tropical Rainforest

5.2.4 End of Topic Test - Weather & Climate

5.3 Tropical Storms

5.3.1 Formation of Tropical Storms

5.3.2 Features of Tropical Storms

5.3.3 The Structure of Tropical Storms

5.3.4 Tropical Storms Case Study: Katrina Effects

5.3.5 Tropical Storms Case Study: Katrina Responses

6 The World of Work

6.1 Tourism

6.1.1 Landscapes

6.1.2 The Growth of Tourism

6.1.3 Benefits of Tourism

6.1.4 Economic Costs of Tourism

6.1.5 Social, Cultural & Environmental Costs of Tourism

6.1.6 Tourism Case Study: Blackpool

6.1.7 Ecotourism

6.1.8 Tourism Case Study: Kenya

7 Natural Resources

7.1.1 What are Rocks?

7.1.2 Types of Rock

7.1.4 The Rock Cycle - Weathering

7.1.5 The Rock Cycle - Erosion

7.1.6 What is Soil?

7.1.7 Soil Profiles

7.1.8 Water

7.1.9 Global Water Demand

7.2 Fossil Fuels

7.2.1 Introduction to Fossil Fuels

7.2.2 Fossil Fuels

7.2.3 The Global Energy Supply

7.2.5 What is Peak Oil?

7.2.6 End of Topic Test - Natural Resources

8.1 River Processes & Landforms

8.1.1 Overview of Rivers

8.1.2 The Bradshaw Model

8.1.3 Erosion

8.1.4 Sediment Transport

8.1.5 River Deposition

8.1.6 River Profiles: Long Profiles

8.1.7 River Profiles: Cross Profiles

8.1.8 Waterfalls & Gorges

8.1.9 Interlocking Spurs

8.1.10 Meanders

8.1.11 Floodplains

8.1.12 Levees

8.1.13 Case Study: River Tees

8.2 Rivers & Flooding

8.2.1 Flood Risk Factors

8.2.2 Flood Management: Hard Engineering

8.2.3 Flood Management: Soft Engineering

8.2.4 Flooding Case Study: Boscastle

8.2.5 Flooding Case Study: Consequences of Boscastle

8.2.6 Flooding Case Study: Responses to Boscastle

8.2.7 Flooding Case Study: Bangladesh

8.2.8 End of Topic Test - Rivers

8.2.9 Rivers Case Study: The Nile

8.2.10 Rivers Case Study: The Mississippi

9.1 Formation of Coastal Landforms

9.1.1 Weathering

9.1.2 Erosion

9.1.3 Headlands & Bays

9.1.4 Caves, Arches & Stacks

9.1.5 Wave-Cut Platforms & Cliffs

9.1.6 Waves

9.1.7 Longshore Drift

9.1.8 Coastal Deposition

9.1.9 Spits, Bars & Sand Dunes

9.2 Coast Management

9.2.1 Management Strategies for Coastal Erosion

9.2.2 Case Study: The Holderness Coast

9.2.3 Case Study: Lyme Regis

9.2.4 End of Topic Test - Coasts

10 Glaciers

10.1 Overview of Glaciers & How They Work

10.1.1 Distribution of Glaciers

10.1.2 Types of Glaciers

10.1.3 The Last Ice Age

10.1.4 Formation & Movement of Glaciers

10.1.5 Shaping of Landscapes by Glaciers

10.1.6 Glacial Landforms Created by Erosion

10.1.7 Glacial Till & Outwash Plain

10.1.8 Moraines

10.1.9 Drumlins & Erratics

10.1.10 End of Topic Tests - Glaciers

10.1.11 Tourism in Glacial Landscapes

10.1.12 Strategies for Coping with Tourists

10.1.13 Case Study - Lake District: Tourism

10.1.14 Case Study - Lake District: Management

11 Tectonics

11.1 Continental Drift & Plate Tectonics

11.1.1 The Theory of Plate Tectonics

11.1.2 The Structure of the Earth

11.1.3 Tectonic Plates

11.1.4 Plate Margins

11.2 Volcanoes

11.2.1 Volcanoes & Their Products

11.2.2 The Development of Volcanoes

11.2.3 Living Near Volcanoes

11.3 Earthquakes

11.3.1 Overview of Earthquakes

11.3.2 Consequences of Earthquakes

11.3.3 Case Study: Christchurch, New Zealand Earthquake

11.4 Tsunamis

11.4.1 Formation of Tsunamis

11.4.2 Case Study: Japan 2010 Tsunami

11.5 Managing the Risk of Volcanoes & Earthquakes

11.5.1 Coping With Earthquakes & Volcanoes

11.5.2 End of Topic Test - Tectonics

12 Climate Change

12.1 The Causes & Consequences of Climate Change

12.1.1 Evidence for Climate Change

12.1.2 Natural Causes of Climate Change

12.1.3 Human Causes of Climate Change

12.1.4 The Greenhouse Effect

12.1.5 Effects of Climate Change on the Environment

12.1.6 Effects of Climate Change on People

12.1.7 Climate Change Predictions

12.1.8 Uncertainty About Future Climate Change

12.1.9 Mitigating Against Climate Change

12.1.10 Adapting to Climate Change

12.1.11 Case Study: Bangladesh

13 Global Population & Inequality

13.1 Global Populations

13.1.1 World Population

13.1.2 Population Structure

13.1.3 Ageing Populations

13.1.4 Youthful Populations

13.1.5 Population Control

13.1.6 Mexico to USA Migration

13.1.7 End of Topic Test - Development & Population

14 Urbanisation

14.1 Urbanisation

14.1.1 Rural Characterisitcs

14.1.2 Urban Characteristics

14.1.3 Urbanisation Growth

14.1.4 The Land Use Model

14.1.5 Rural-Urban Pull Factors

14.1.6 Rural-Urban Push Factors

14.1.7 The Impacts of Migration

14.1.8 Challenges of Urban Areas in Developed Countries

14.1.9 Challenges of Urban Areas in Developing Countries

14.1.10 Urban Sustainability

14.1.11 Case Study: China's Urbanisation

14.1.12 Major UK Cities

14.1.13 Urbanisation in the UK

14.1.14 End of Topic Test- Urbanisation

14.1.15 End of Topic Test - Urban Issues

15 Ecosystems

15.1 The Major Biomes

15.1.1 Distribution of Major Biomes

15.1.2 What Affects the Distribution of Biomes?

15.1.3 Biome Features: Tropical Forests

15.1.4 Biome Features: Temperate Forests

15.1.5 Biome Features: Tundra

15.1.6 Biome Features: Deserts

15.1.7 Biome Features: Tropical Grasslands

15.1.8 Biome Features: Temperate Grasslands

15.2 Case Study: The Amazon Rainforest

15.2.1 Interdependence of Rainforest Ecosystems

15.2.2 Nutrient Cycling in Tropical Rainforests

15.2.3 Deforestation in the Amazon

15.2.4 Impacts of Deforestation in the Amazon

15.2.5 Protecting the Amazon

15.2.6 Adaptations of Plants to Rainforests

15.2.7 Adaptations of Animals to Rainforests

16 Life in an Emerging Country

16.1 Case Studies

16.1.1 Mumbai: Opportunities

16.1.2 Mumbai: Challenges

17 Analysis of Africa

17.1 Africa

17.1.1 Desert Biomes in Africa

17.1.2 The Semi-Desert Biome

17.1.3 The Savanna Biome

17.1.4 Overview of Tropical Rainforests

17.1.5 Colonisation History

17.1.6 Population Distribution in Africa

17.1.7 Economic Resources in Africa

17.1.8 Urbanisation in Africa

17.1.9 Africa's Location

17.1.10 Physical Geography of Africa

17.1.11 Desertification in Africa

17.1.12 Reducing the Risk of Desertification

17.1.13 Case Study: The Sahara Desert - Opportunities

17.1.14 Case Study: The Sahara Desert - Development

18 Analysis of India

18.1 India - Physical Geography

18.1.1 Geographical Location of India

18.1.2 Physical Geography of India

18.1.3 India's Climate

18.1.4 Natural Disasters in India

18.1.5 Case Study: The Thar Desert

18.1.6 Case Study: The Thar Desert - Challenges

18.2 India - Human Geography

18.2.1 Population Distribution in India

18.2.2 Urabinsation in India

18.2.3 The History of India

18.2.4 Economic Resources in India

19 Analysis of the Middle East

19.1 The Middle East

19.1.1 Physical Geography of the Middle East

19.1.2 Human Geography of the Middle East

19.1.3 Climate Zones in the Middle East

19.1.4 Climate Comparison with the UK

19.1.5 Oil & Natural Gas in the Middle East

19.1.6 Water in the Middle East

19.1.7 Population of the Middle East

19.1.8 Development Case Studies: The UAE

19.1.9 Development Case Studies: Yemen

19.1.10 Supporting Development in Yemen

19.1.11 Connection to the UK

19.1.12 Importance of Oil

19.1.13 Oil & Tourism in the UAE

20 Analysis of Bangladesh

20.1 Bangladesh Physical Geography

20.1.1 Location of Bangladesh

20.1.2 Climate of Bangladesh

20.1.3 Rivers in Bangladesh

20.1.4 Flooding in Bangladesh

20.2 Bangladesh Human Geography

20.2.1 Population Structure in Bangladesh

20.2.2 Urbanisation in Bangladesh

20.2.3 Bangladesh's Economy

20.2.4 Energy & Sustainability in Bangladesh

21 Analysis of Russia

21.1 Russia's Physical Geography

21.1.1 Russia's Climate

21.1.2 Russia's Landscape

21.2 Russia's Human Geography

21.2.1 Population of Russia

21.2.2 Russia's Economy

21.2.3 Energy & Sustainability in Russia

Jump to other topics

Unlock your full potential with GoStudent tutoring

Affordable 1:1 tutoring from the comfort of your home

Tutors are matched to your specific learning needs

30+ school subjects covered

What are Rocks?

- DOI: 10.1080/21568316.2024.2366402

- Corpus ID: 271081066

Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Tourism in Tourist Destinations: A Qualitative Case Study from Türkiye

- David A. Fennell , Kadir Çakar , +1 author İsmail Uzut

- Published in Tourism Planning &… 7 July 2024

- Environmental Science, Business

- Tourism Planning & Development

76 References

Tourism and development theory: which way now, exploring residents’ perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable tourism development in traditional villages: the lens of stakeholder theory, overtourism in istanbul: an interpretative study of non-governmental organizational views, effects of agritourism businesses’ strategies to cope with the covid-19 crisis: the key role of corporate social responsibility (csr) behaviours, migration, tourism and social sustainability, does firms’ csr engagement support tourism sector development moderation effect of csr committee and ceo duality, stakeholders’ attitudes towards tools for sustainable tourism in historical cities, obstacles and possibilities in archival research: archives as a data source for leisure scholars in lockdown, communicating sustainability and ecotourism principles by ecolodges: a global analysis, integrating theory in co-design: an abductive approach, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

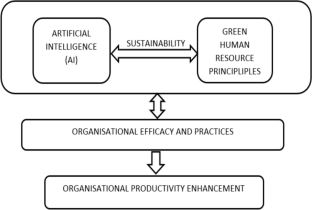

Green Human Resource Management and Its Sustainable Organizational Practices in Hospitality Industry in India

- Published: 12 July 2024

Cite this article

- Vaishali Gupta ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0005-9753-407X 1 &

- Monika Arora 1

Explore all metrics

Tourism and hospitality industry has been playing a very important role in recent years in increasing the Indian economic growth. Currently, the big push provided by the Government of India to revitalize tourism industry in our country opens up immense opportunities. Today, there is a high potential to upgrade the practice of green human resource (HR) culture whereby aspects such as employee empowerment, employee motivation, training and development, spirituality, sustainability, and ethical business practices are paramount. Employees are focusing on fostering camaraderie and collegiality through workplace spirituality and organizational engagement, which is supported by Green HR-based policies and procedures. This research is based on primary and secondary data along with case study interpretation. This research paper concludes that green human resource practices (GHRP) enhance the organizational citizenship behavior of employees leading to sustainability and inclusiveness.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Is There a Dark Side to Green Human Resource Management? Evidence from India

Green human resource management: a need of time and a sustainable solution for organizations and environment

Understanding employee ecological behavior in malaysian higher educational institutes through green hrm practices, data availability.

The data can be available as per the request of the reader.

Ababneh, O. M. A. (2021). How do green HRM practices affect employees’ green behaviors? The Role of Employee Engagement and Personality Attributes, 64 (7), 1204–1226. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1814708

Article Google Scholar

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2018). The race between man and machine: Implications of technology for growth, factor shares, and employment. American economic review, 108 (6), 1488–1542.

Al Naqbi, H., Bahroun, Z., & Ahmed, V. (2024). Enhancing work productivity through generative artificial intelligence: A comprehensive literature review. Sustainability 16 (3)1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU16031166

AlKahtani, N. S., Iqbal, S., Sohail, M., Sheraz, F., Jahan, S., Anwar, B., & Haider, S. A. (2021). Impact of employee empowerment on organizational commitment through job satisfaction in four and five stars hotel industry. Management Science Letters , 813–822. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2020.10.022

Amrutha, V. N., & Geetha, S. N. (2020a). A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. In Journal of Cleaner Production (Vol. 247). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119131

Amrutha, V. N., & Geetha, S. N. (2020b). A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 247 , 119131. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2019.119131

Arici, H. E., & Uysal, M. (2021). Leadership, green innovation, and green creativity: A systematic review. 42 (5–6), 280–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2021.1964482

Arora, M., & Bhardwaj, I. (2022). Modern Education and Computer. Science, 1 (1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijmecs.2022.01.04

Arora, M., Bhardwaj, I., & Sonia. (2022). The emergence of sustainability adoption in the healthcare sector during COVID-19. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, 392 , 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0619-0_2

Astakhova, E. V., Ivanova, O. A., & Khilkovskaya, A. A. (2019). Labor stimulation construction scale on the modern production enterprise. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science , 272 (3). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/272/3/032217

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management, 17 (1), 99–120.

Benevene, P., & Buonomo, I. (2020). Green human resource management An evidence-based systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12 (15), 5974. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12155974

Bragas, C., Bragas, L. F., & Soliman, C. (2022). The changing workforce and its implications to productivity: A literature review. Sachetas, 1 (2), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.55955/120005

Cabral, C., & Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J. (2020). Understanding the human side of green hospitality management. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88 , 102389. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2019.102389

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance*. Journal of Management Studies, 44 (6), 972–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-6486.2007.00691.X

Chen, C. C., & Yao, J. Y. (2018). What drives impulse buying behaviors in a mobile auction? The perspective of the stimulus-organism-response model. Telematics and Informatics, 35 (5), 1249–1262. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TELE.2018.02.007

Chi, C. G., & Gursoy, D. (2009). Employee satisfaction, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: An empirical examination. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28 (2), 245–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.08.003

Chowdhury, S., Dey, P., Joel-Edgar, S., Bhattacharya, S., Rodriguez-Espindola, O., Abadie, A., & Truong, L. (2022). Unlocking the value of artificial intelligence in human resource management through AI capability framework. Human Resource Management Review , 100899. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRMR.2022.100899

Daud, I., Edya Rosadi, M., Kalimantan Muhammad Arsyad Al Banjari Banjarmasin, I., & Corresponding Author, I. (2023). AI implementation impact on workforce productivity: The role of AI training and organizational adaptation. Escalate : Economics and Business Journal , 1 (01), 01–13. https://doi.org/10.61536/ESCALATE.V1I01.6

Dey, P. K., Malesios, C., De, D., Chowdhury, S., & Abdelaziz, F. B. (2019). Could lean practices and process innovation enhance supply chain sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises? Business Strategy and the Environment, 28 (4), 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1002/BSE.2266

Fujimura, K. (2020). Constructing a work motivation model based on “benefit delay” and “benefit enjoyment.” Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 961 , 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20154-8_24

Geiger, S. M., Grossman, P., & Schrader, U. (2019). Mindfulness and sustainability: Correlation or causation? Current Opinion in Psychology, 28 , 23–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COPSYC.2018.09.010

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2010). Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational Performance , 1–360. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315703817

Hadi, M. U., tashi, qasem al, Qureshi, R., Shah, A., muneer, amgad, Irfan, M., Zafar, A., Shaikh, M. B., Akhtar, N., Wu, J., & Mirjalili, S. (2023). Large language models: A comprehensive survey of its applications, challenges, limitations, and future prospects. Authorea Preprints . https://doi.org/10.36227/TECHRXIV.23589741.V4

India: Travel and tourism total impact to GDP | Statista . (n.d.). Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/313724/total-contribution-of-travel-and-tourism-to-gdp-in-india-by-segment/

Inoue, Y., & Lee, S. (2011). Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tourism Management, 32 (4), 790–804. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2010.06.019

Ivanov, S., & Umbrello, S. (2021). The ethics of artificial intelligence and robotization in tourism and hospitality-a conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Smart Tourism, 1 (4), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.52255/smarttourism.2021.1.4.3

Jabbour, C. J. C., Santos, F. C. A., & Nagano, M. S. (2010). Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: Methodological triangulation applied to companies in Brazil. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21 (7), 1049–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585191003783512

Jarrahi, M. H. (2018). Artificial intelligence and the future of work: Human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making. Business horizons, 61 (4), 577–586.

Kang, K. H., Lee, S., & Huh, C. (2010). Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29 (1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2009.05.006

Karatepe, O. M., Hsieh, H., & Aboramadan, M. (2022). The effects of green human resource management and perceived organizational support for the environment on green and non-green hotel employee outcomes. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 103 , 103202. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2022.103202

Kim, J., Song, H. J., Lee, C. K., & Lee, J. Y. (2017). The impact of four CSR dimensions on a gaming company’s image and customers’ revisit intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61 , 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2016.11.005

Kim, Y. J., Kim, W. G., Choi, H. M., & Phetvaroon, K. (2019). The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76 , 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2018.04.007

Klenke, K. (2005). Corporate values as multi-level, multi-domain antecedents of leader behaviors. In International Journal of Manpower, 26 (1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720510587271

Leonidou, L. C., Leonidou, C. N., Fotiadis, T. A., & Zeriti, A. (2013). Resources and capabilities as drivers of hotel environmental marketing strategy: Implications for competitive advantage and performance. Tourism Management, 35 , 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2012.06.003

Li, R., & Ramanathan, R. (2018). Exploring the relationships between different types of environmental regulations and environmental performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 196 , 1329–1340. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2018.06.132

Liu, B., & Perry, J. L. (2014). The psychological mechanisms of public service motivation. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36 (1), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X14549672

Maletič, M., Maletič, D., Dahlgaard, J. J., Dahlgaard-Park, S. M., & Gomišček, B. (2015). Effect of sustainability-oriented innovation practices on the overall organisational performance: An empirical examination. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 27 (9–10), 1171–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015.1064767

Mayer, A.S., Strich, F., & Fiedler, M. (2020). Unintended Consequences of Introducing AI Systems for Decision Making. MIS Quarterly Executive, 19 (4).

Mekoth, N., Prabhudesai, R., & Tari, S. (2024). Implications of HR managers’ green attitude: A study of Indian hospitality sector. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness , ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-05-2023-0219/FULL/XML

Monod, E., Watson-Manheim, M. B., Qi, I., Joyce, E., Mayer, A. S., & Santoro, F. (2023). (Un)intended consequences of AI sales assistants. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 63 (2), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2022.2067794

Monod, E., Mayer, A. S., Straub, D., Joyce, E., & Qi, J. (2024). From worker empowerment to managerial control: The devolution of AI tools’ intended positive implementation to their negative consequences. Information and Organization, 34 (1), 100498. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INFOANDORG.2023.100498

Narayanan, V., & Adams. (2016). Citation for published item: Transformative change towards sustainability: The interaction between organisational discourses and organisational practices . https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2016.1257930

Nwanzu, C. L., & Babalola, S. S. (2019a). Predictive relationship between sustainable organisational practices and organisational effectiveness: The mediating role of organisational identification and organisation-based self-esteem. Sustainability, 11 (12), 3440. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123440

Nwanzu, C. L., & Babalola, S. S. (2019). Predictive relationship between sustainable organisational practices and organisational effectiveness: The mediating role of organisational identification and organisation-based self-esteem. Sustainability, 11 (12), 3440. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU11123440

Opatha, H. H. D. N. P. (2013). Green human resource management: A simplified introduction human resource management jobs and their requirments view project . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301886703 . Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

Otaye-Ebede, L., Shaffakat, S., & Foster, S. (2020). A multilevel model examining the relationships between workplace spirituality, ethical climate and outcomes: A social cognitive theory perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 166 (3), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04133-8

Patil A. (2022). How AI is changing hospitality industry. Economictimes.Com , https://hospitality.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/speaking-heads/how-ai-is-changinghospitality-industry/92812751 . Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

Paulet, R., Holland, P., & Morgan, D. (2021). A meta-review of 10 years of green human resource management: Is Green HRM headed towards a roadblock or a revitalisation? Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59 (2), 159–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12285

Pawinee Petchsawang & Gary N. McLean. (2017). Workplace spirituality, mindfulness meditation, and work engagement. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion. , 1–30. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pawinee-Petchsawang/publication/314027099_Workplace_spirituality_mindfulness_meditation_and_work_engagement/links/5e5be9a692851cefa1d48d85/Workplace-spirituality-mindfulness-meditation-and-work-engagement.pdf

Pham, N. T., Tučková, Z., & Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J. (2019). Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tourism Management, 72 , 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.12.008

Predeus, N. V., Baryshnikova, N. A., & Altukhov, A. L. (2018). Algorithm of development of motivation system of industrial enterprise personnel. Smart Technologies and Innovations in Design for Control of Technological Processes and Objects: Economy and Production, 138 , 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15577-3_30

Randell, R., Honey, S., Alvarado, N., Greenhalgh, J., Hindmarsh, J., Pearman, A., Jayne, D., Gardner, P., Gill, A., Kotze, A., & Dowding, D. (2019). Factors supporting and constraining the implementation of robot-assisted surgery: A realist interview study. BMJ Open , 9 (6). https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2018-028635

Rasool, S. F., Samma, M., Wang, M., Zhao, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2019). How human resource management practices translate into sustainable organizational performance: The mediating role of product, process and knowledge innovation. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 12 , 1009–1025. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S204662

Rakesh D. Rauta, Balkrishna Narkhedeb, & Bhaskar B. Gardas. (2016). To identify the critical success factors of sustainable supply chain management practices in the context of oil and gas industries: ISM approach. Elsevier , 1–15. https://fardapaper.ir/mohavaha/uploads/2018/09/Fardapaper-To-identify-the-critical-success-factors-of-sustainable-supply-chain-management-practices-in-the-context-of-oil-and-gas-industries-ISM-approach.pdf . Accessed 4 Feb 2023.

Ren, S., Tang, G., Jackson, E., & S. (2018). Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35 (3), 769–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10490-017-9532-1/METRICS

Rhou, Y., Singal, M., & Koh, Y. (2016). CSR and financial performance: The role of CSR awareness in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57 , 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHM.2016.05.007

Rotich, R. K., & Rotich, R. K. (2016). The impact of organizational-based self esteem on work engagement among state corporations employees in Kenya. European Journal of Business and Management, 8 (15), 114–124.

Rubel, M. R. B., Kee, D. M. H., & Rimi, N. N. (2020). The influence of green HRM practices on green service behaviors: The mediating effect of green knowledge sharing. Employee Relations, 43 (5), 996–1015. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2020-0163

Schedlitzki, D. (2019). Developing apprentice leaders through critical reflection. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9 (2), 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-09-2018-0095/FULL/XML

Song, Y., & Wu, R. (2021). Analysing human-computer interaction behaviour in human resource management system based on artificial intelligence technology. Knowledge Management Research and Practice . https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2021.1955630

Stahl, G. K., Brewster, C. J., Collings, D. G., & Hajro, A. (2020). Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Human Resource Management Review , 30 (3). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100708

Tanova, C., & Bayighomog, S. W. (2022). Green human resource management in service industries: The construct, antecedents, consequences, and outlook. Service Industries Journal, 42 (5–6), 412–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2045279

Tariq, S., Jan, F. A., & Ahmad, M. S. (2016). Green employee empowerment: A systematic literature review on state-of-art in green human resource management. Quality and Quantity, 50 (1), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-014-0146-0

Taylor, S., Osland, J., & Egri, C. P. (2012). Guest editors’ introduction: Introduction to HRM’s role in sustainability: Systems, strategies, and practices. Human Resource Management, 51 (6), 789–798. https://doi.org/10.1002/HRM.21509

Teo, T., Unwin, S., Scherer, R., & Gardiner, V. (2021). Initial teacher training for twenty-first century skills in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (IR 4.0): A scoping review. Computers & Education, 170 , 104223. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2021.104223

The hospitality Industry in India: An overview . (n.d.). Retrieved November 22, 2022, from https://www.newshour.press/hospitality-industry-in-india-an-overview/

Theodoulidis, B., Diaz, D., Crotto, F., & Rancati, E. (2017). Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tourism Management, 62 , 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2017.03.018

Thomson, I. (2011). Is Accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability… and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 31 (1), 99–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160x.2011.556420

Tiwari, P., Pandey, R., Garg, V., & Singhal, A. (2021). Application of artificial intelligence in human resource management practices. Proceedings of the Confluence 2021: 11th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science and Engineering . https://doi.org/10.1109/Confluence51648.2021.9377160

Úbeda-García, M., Claver-Cortés, E., Marco-Lajara, B., & Zaragoza-Sáez, P. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the hotel industry. The mediating role of green human resource management and environmental outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 123 , 148–2963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.055

Ünal, Z. M., & Turgut, T. (2016). Organizational culture and organization based selfesteem as predictors of spirit at work. Khazar Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences , 19 (4). http://dspace.khazar.org/handle/20.500.12323/3469 . Accessed 20 Feb 2023.

Vinichenko, M. V., Chulanova, O. L., Rybakova, M. V., Melnichuk, A. V., Makushkin, S. A., & Malyshev, M. A. (2019). Fostering talented employees’ loyalty in circumstances where artificial intelligence is applied. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8 (3), 7406–7410. https://doi.org/10.35940/IJRTE.C6151.098319

Vinichenko, M. V, Melnichuk, A. V, & Karácsony, P. (2020). Entrepreneurship and sustainability issues . 7 (4). https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2020.7.4(9 )

Yassin Alzyoud, A. A. (2022). Artificial intelligence for sustaining green human resource management: A literature review . 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETSIS55481.2022.9888840

Yong, J. Y., Yusliza, M. Y., Ramayah, T., Chiappetta Jabbour, C. J., Sehnem, S., & Mani, V. (2020). Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29 (1), 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2359

Zanzotto, F. M. (2019). Human-in-the-loop artificial intelligence. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 64 , 243–252.

Zhang, H., Song, M., & He, H. (2020). Achieving the success of sustainability development projects through big data analytics and artificial intelligence capability. Sustainability (Switzerland) , 12 (3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030949

Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J., & Lai, K. H. (2012). Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. International journal of production research, 50 (5), 1377–1394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2011.571937

Zibarras, L. D., & Coan, P. (2015). HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26 (16), 2121–2142. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2014.972429

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Amity Business School, Amity University Haryana, Gurgaon, Haryana, India

Vaishali Gupta & Monika Arora

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vaishali Gupta .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. Questions related to green human resource: based on personal interview

Here, we try to relate green human resource practices with green human resource management considering triple bottom line—employee empowerment, motivation, training and development, workplace spirituality, and ethical business practices.

Q1. Can you let me know about some of the best green human resource practices for a famous chain hotel which can set an example for others to follow green human resource practices?

Q2. Do you feel green human resource practices should be followed by every organization?

Q3. Does implementing green human resource practices give any impact in molding the employee’s behavior towards productive working?

Q4. What are the favorable changes that are seen in employees after following green human resource practices?

Q5. Is there any effect of green human resource practices on digital human resource management?

Q6. Does regular motivation of employee help to bring out the best potential and create spiritual behavior within employees?

Q7. Do you appreciate formation of informal groups or communication for discussing organizational goals inside your organizations, as sometimes informal communications bring out the best ideas of all?

Q8. What are some of the barriers that hospitality industry face while implementing green human resource practices?

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gupta, V., Arora, M. Green Human Resource Management and Its Sustainable Organizational Practices in Hospitality Industry in India. J Knowl Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-02207-1

Download citation

Received : 25 May 2023

Accepted : 23 June 2024

Published : 12 July 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-024-02207-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Green human resource management

- Employee empowerment

- Artificial intelligence

- Employee satisfaction

- Workplace spirituality

- Ethical work practices

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

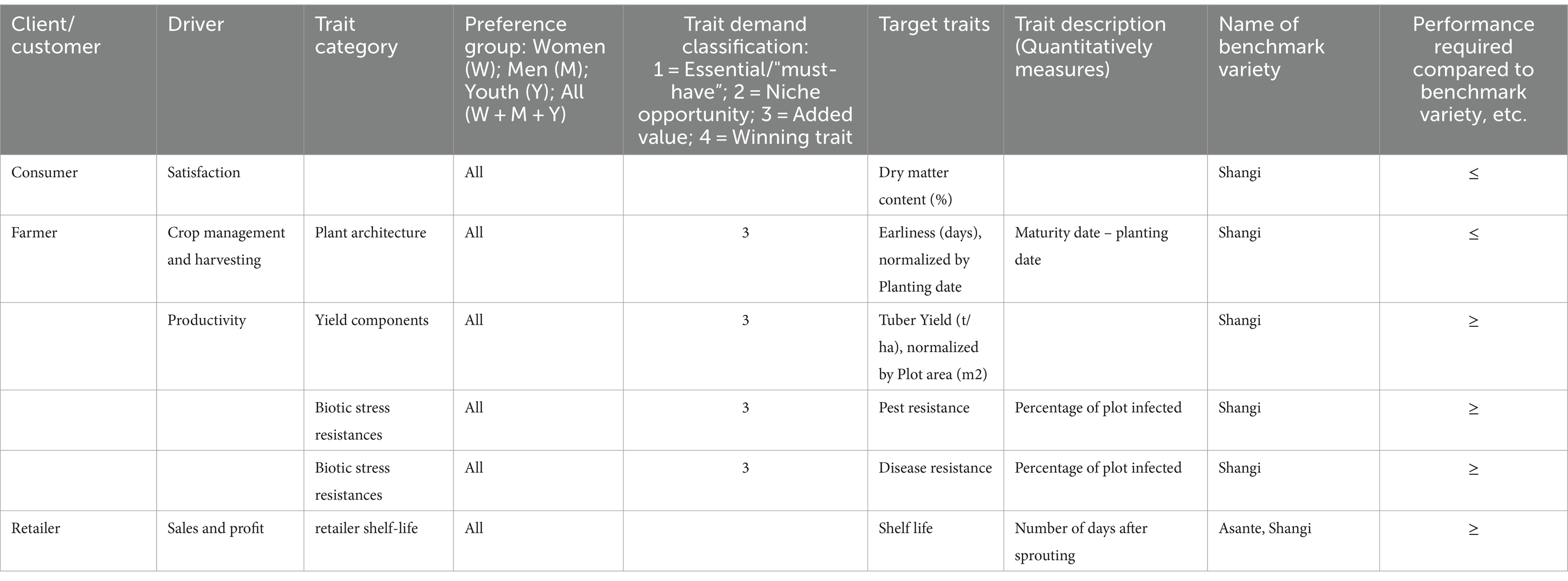

A gendered assessment of crop traits to improve breeding product design and uptake: the case of potato in kenya.

- 1 School of Global Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

- 2 Norwich Institute Sustainable Development, Norwich, United Kingdom

- 3 International Potato Center, Kampala, Uganda

- 4 Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

- 5 Syngenta Foundation, Angers, France

- 6 International Potato Center, Lima, Peru

- 7 Independent Consultant, Portland, OR, United States

The study assesses the gender implications of a target product profile for table potato in Kenya. Breeding programs mostly emphasize farmers’ trait requirements and rarely pay attention to other value chain actors’ preferences. This partially contributes to the low uptake of improved varieties. Therefore, efforts are required to assess the gender implications of crop product profile proposals during development, testing, and dissemination. In this paper, we assess the gender implications of traits targeted by a potato breeding program in Kenya using the G+ tools. The study applies the G+ product profile tool to examine the instances the selected traits may exacerbate gender disparity along four domains: unpaid labor, access to employment opportunities, requiring extra inputs and control over benefits. We use mixed methods including a review by social scientists, key informant interviews and a multistakeholder workshop to gather insights from female and male farmers, breeders, and other stakeholders. Findings show that pest, disease resistance, and shelf-life traits benefit women and men in the target customer segments. On the other hand, earliness, dry matter, and yield could increase drudgery for women. The traits increase demand for women’s unpaid labor during harvesting, sorting and food preparation time while also displacing women from profitable nodes. We recommend that gender-responsive strategies accompany the release of the target variety to mitigate inequities and enhance adoption.

1 Introduction

A senior breeder recently said at a multistakeholder meeting convened to map trait preferences of different breeding customers: “We breed for all people, not women.” Many breeders share this sentiment. That is, there is little recognition that breeding customers extend beyond the farm and are a heterogeneous group of actors along the value chain actors with different interests. The disconnect between breeders’ and customers’ preferences arises from a lack of interest in each other’s perspectives ( Haverkort et al., 2022 ). Participatory Plant Breeding (PPB) and Participatory Variety Selection (PVS) were introduced to address the divide and dominance of breeders’ priorities in designing new varietal traits and accelerate the adoption of customer preferred traits. Nonetheless, despite considerable gains in breeding programs, the input of men and women across crop value chains in the traits they would like to see in improved varieties is uneven. There has been slow progress in the incorporation of gender preferences in breeding processes, even with the recognition that this could help increase adoption. The failure to consider the varietal and trait preferences of heterogeneous customers is linked to the low adoption of improved varieties developed by the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research and National Research Institutions ( McEwan et al., 2021 ; Thiele et al., 2021 ). Consumption traits that are hardly considered have a significant role in impeding adoption ( Walker and Alwang, 2015 ). While improved disease resistance motivates adoption, “entrenched consumption preferences are major constraints to adoption.”

The PPB and PVS processes were to get information from all customers (consumers, traders and the industry) besides the farmers for poorly understood varietal traits ( Walker, 2006 ). Conversely, plant breeders have used these approaches mainly to get feedback from farmers albeit late in the breeding process. The feedback has also tended to focus on the elite clones developed on-station ( Almekinders et al., 2006 ). Failure to consider the trait preferences of the broader group of breeding customers along the entire value chain leads to the promotion of unsuitable varieties, resulting in low adoption rates among important actors ( Muhinyuza et al., 2016 ). For example, Kisakye et al. (2020) found that in Uganda, the desired characteristics of raw potatoes differ among stakeholders in the potato industry. Producers, traders, and consumers prefer potatoes with red skin color, yellow flesh color, smooth skin, and big size tubers. On the other hand, processors favor potatoes with white/cream flesh color, medium to large size, shallow eye depth, smooth skin, and high dry matter content.

Gendered trait preference of value chain actors predisposes women to lower adoption of certain improved varieties ( Mudege et al., 2021 ). New crop varieties might possess traits that inadvertently disadvantage women, leading to an increase in their workload or necessitating additional inputs that women have limited access to compared to men ( Kramer and Galiè, 2020 ). Women usually prioritize culinary traits in relation to their caregiving roles, while men opt for market-preferred traits ( Mudege et al., 2021 ). Differences in trait preference are related to the varying actors’ roles in the crop value chains ( Okonya et al., 2019 ). Banana, cassava, and potato studies show that the preference for traits varies with the sociocultural context, gendered labor, and access to markets. Rather than conforming to rigid, binary models where women and men have distinctly different preferences, there exists an overlap ( McDougall et al., 2022 ). Female cassava processors prioritize culinary traits that are given low priority in breeding profiles ( Teeken et al., 2018 ). Male processors tend to focus on agronomic traits with preferences depending on geography and religion. Male and female banana growers’ trait preferences differ and align with gender-specific roles. Female farmers are involved in cooking and male farmers in the manufacture of beer ( Marimo et al., 2020 ). While men and women have common preferences in traits such as drought tolerance and pest resistance, there are gender variations for attributes such as seed coat color ( Jinbaani et al., 2023 ).

Breeding programs have to understand their clientele and take into account their varying roles, choices, and the implications of varietal traits on the different gender categories. There is a consensus on the significance of breeding programs being more gender-responsive but treading unfamiliar territory. A primary obstacle is the absence of data on gendered preferences and the incomplete knowledge/expertise of how to incorporate this information into the different phases of breeding profile building. In this paper, therefore, we apply the G+ tools ( Ashby and Polar, 2021a ) to interrogate, with a gender lens, a target product profile (TPP) for table potato in Kenya with the Shangi variety as the benchmark. The paper specifically examines the use of the G+ tools under three settings, namely: (1) review by social scientists based on their expertise with support from existing literature; (2) subjecting the G+ tools to opinions of key informants drawn from across potato value chain; and (3) administering the G+ tools to participants in a multistakeholder workshop involving breeders, agronomists, social scientists and customers representing key roles or functions in the potato value chain. The specific objectives of this paper are:

i. Assess the gender implications of each trait in the table potato target product profile using the G+ tools.

ii. Compare the outcome of G+ tools in assessing varieties of traits under different methods.

2 Study context

Potato is a major crop in tropical highlands of sub-Sahara Africa (SSA). With approximately 800,000 farmers in potato cultivation, potatoes have emerged as Kenya’s second most important food crop, gaining popularity in 15 counties, particularly in the Rift Valley and Western regions ( CIP, 2019 ). Due to its productivity per unit area and time, potato cultivation holds significant promise in ensuring food security ( Muthoni et al., 2013 ). It reduces poverty by serving as a livelihood source for farmers and individuals involved in the value chain ( Gikundi et al., 2023 ). According to the National Potato Council of Kenya, consumption projection by 2022 was 2.3 million Metric Tons, with an average consumption per person of 5 kilograms per year. A 40% increase in the number of farmers growing potatoes could lead to a 0.3% boost in Kenya’s GDP ( National Potato Council of Kenya, 2023 ). The varieties grown include Unica, Dutch Robijn, Asante, Tigoni, Desiree, Kenya Karibu, Kenya Sifa, Sherehekea and Shangi. Shangi is incredibly popular and currently commands an estimated 80% market share ( National Potato Council of Kenya, 2023 ). Shangi’s popularity can be attributed to its appropriateness for boiling, shorter cooking time, early maturation, large tubers, and high yields ( Sinelle, 2018 ).

For decades, breeders have strived to introduce new potato varieties in SSA to improve production and productivity. While these efforts have led to the release of new varieties, only a few are utilized by farmers ( Mumia et al., 2018 ). The study emphasizes the limited attention breeding programs paid to quality traits, which consumers, especially women, prioritize when selecting table potatoes. Further, it notes that potato breeding has focused on disease and climate change resilience, ignoring marketability and cooking quality traits which are central to end users’ preferences. Insufficient attention paid to consumer-preferred traits has led to low adoption of roots, tuber and banana modern varieties but there is a paucity of ample evidence to determine whether the neglect of gender differences among users contributed to low adoption ( Thiele et al., 2021 ). The gender dimension of low adoption of improved varieties has been explored recently, and findings indicate a paucity of research on gender-specific potato trait preferences ( Mudege et al., 2021 ).

Gender roles determine access to knowledge, resources (including plant genetic resources), decision-making, labor allocation and control over benefits and employment, all of which have a role in varietal adoption decisions ( Tufan et al., 2018 ). The actor’s role in the value chain, individual and household characteristics, and cultural factors influenced end-users’ prioritization of traits ( Weltzien et al., 2019 ; Marimo et al., 2020 ). Gender-specific preferences and intrinsic cooking quality characteristics such as color, flavor, and text were critical to adopting new hybrid banana varieties ( Nasirumbi Sanya et al., 2017 ). Understanding gendered trait preferences as an expression of underlying structural gender inequalities in assets, resources and opportunities for growing and processing a crop can help breeders assess demand for new varieties that address gender-specific objectives for food, nutrition or economic security ( Polar et al., 2022 ). Weltzien et al. (2019) portray the adoption of new crop varieties as a coping strategy in the face of changes in agroecological and social conditions that are major transformative factors of farm and food systems. Production goals (subsistence versus commercial), understood as coping strategies, can often differ by gender and may play a significant role in the varietal preferences of women and men. Women often prioritize production for home consumption and usage traits, and men favor market traits, reflecting their unequal access to markets and commercial opportunities ( Elango and Kawarazuka, 2019 ).

In Uganda, Mudege et al. (2021) , while developing a gendered product profile for boiled potatoes, concluded that in addition to agronomic traits, breeders need to consider how gender roles and social norms condition market relationships and feed into trait preferences which influence the selection of new varieties by farmers. Household members are employed, among others, as producers, hired farm labor providers, and pesticide applicators, and they provide significant unpaid family labor. Women mostly engage in seed conservation, establishment, weeding, roguing, harvesting and packaging. These activities are not mechanized, are backbreaking, and are offered as unpaid family labor. Men are involved in initial land preparation, pesticide application, transportation and selling to urban markets ( Okello et al., 2020 ).

In contrast to activities done by women, men-led activities are mechanized and geared towards commercialization. For example, land preparation is done using oxen ploughs. With the commercialization of potatoes, men can hire labor in joint activities like pest and disease control; women fetch the water for mixing chemicals while men operate the spray pumps ( Okello et al., 2020 ). Further, even when it comes to participation in profitable activities such as seed production, it is estimated that 78% are men ( Sebatta et al., 2014 ). Potato contributes 22% of the income for male farmers transitioning from subsistence farming to commercial compared to 17% for women ( Mugisha et al., 2017 ). Men are the main price negotiators in commercial potato production ( Kyomugisha et al., 2017 ). Commercial potato seed production is a male niche because women lack productive resources. At the household level, gender disparities exist concerning access to products and services offered by upstream (such as seed traders and extension workers) and downstream actors (such as traders/marketers, transporters, processors and consumers). For instance, women have limited access to agricultural extension services, improved seeds, fertilizer and pesticides mainly due to low mobility and purchasing power ( Kisakye et al., 2020 ; Mudege et al., 2020 ; Puskur et al., 2021 ). This is compounded by their limited access to and control over benefits from the potato enterprise. The above findings call for gender mainstreaming across the breeding pipeline, i.e., from setting breeding objectives to varietal release and dissemination. Specifically, there is a need to assess the effects breeding for specific traits can have on men and women.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 the g+ tools.

The G+ tools are a suite of three tools which assess the gender-responsiveness of target or actual breeding product profiles at the variety design stage and other stages of varietal development. The tools include (i) the G+ Customer Profile tool ( Orr et al., 2021 ), (ii) the G+ Product Profile Query tool ( Ashby and Polar, 2021a ) and (iii) the G+ Standard Operating Procedure tool ( Ashby and Polar, 2021b ). The G+ Customer Profile organizes the evidence from gender analysis, including information on how men and women value important plant traits, to decide which customer segments to prioritize using a socially inclusive and gender perspective ( Orr et al., 2021 ). For a specific customer, the G+ Product Profile Query (G + PP) appraises each trait proposed for inclusion in the design of a variety, i.e., Product Profile ( Ashby and Polar, 2021a ). Together, they provide a framework for multidisciplinary research teams to incorporate the results of gender analysis into two decisions that public-sector plant breeders routinely make for variety development. These are (i) the intended customers of the plant breeding products, that is, varieties and (ii) the important features of the breeding product intended for this customer. The tools have been piloted in sweetpotato (Uganda), beans (Kenya), cassava (Nigeria), bananas (Uganda) and lentils (Morocco) value chains ( Polar et al., 2022 ).

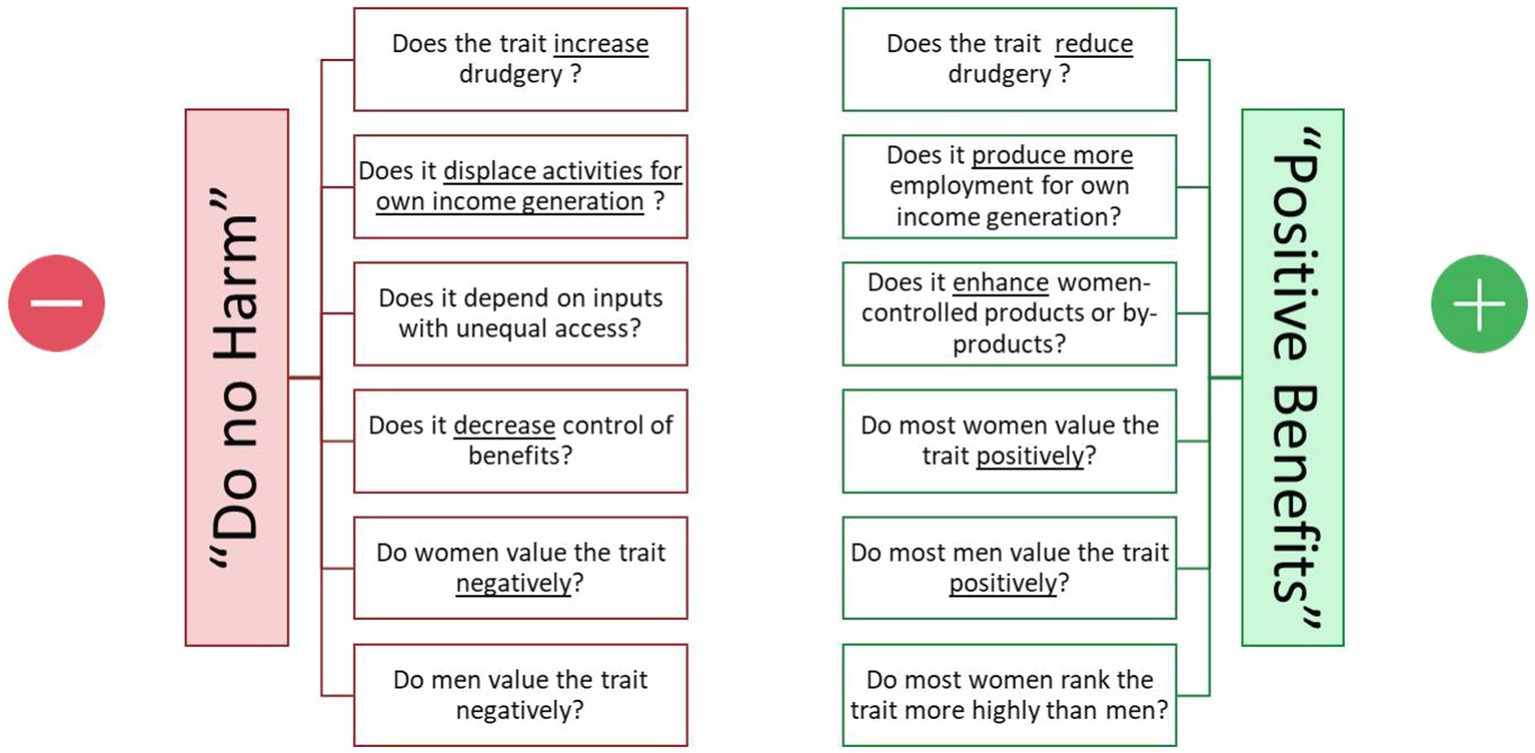

In this study, we applied the G+ PP tool. This tool organizes and synthesizes the evidence from gender analysis so that the breeding team makes evidence-based judgments to evaluate each trait’s positive and negative features from a gender perspective. Specifically, the G+ PP tool assigns two “gender impact” scores to each trait in a product profile: (i) a negative or neutral score based on a “do no harm” analysis and (ii) a positive or neutral score based on a gendered analysis of the benefits of each trait. Scoring is similar to the nominal index breeders use to assign a value for disease tolerance of a variety. The tool requires the breeding team to make the final choice or trade-off, between the positive and negative gender aspects of each trait analyzed by providing a traffic light warning system: (i) Stop- there’s a risk of overlooking an important gender inequality (ii) Take care- there are ambiguous gender inequality outcomes or (iii) Go- a gender-neutral or beneficial outcome is possible.

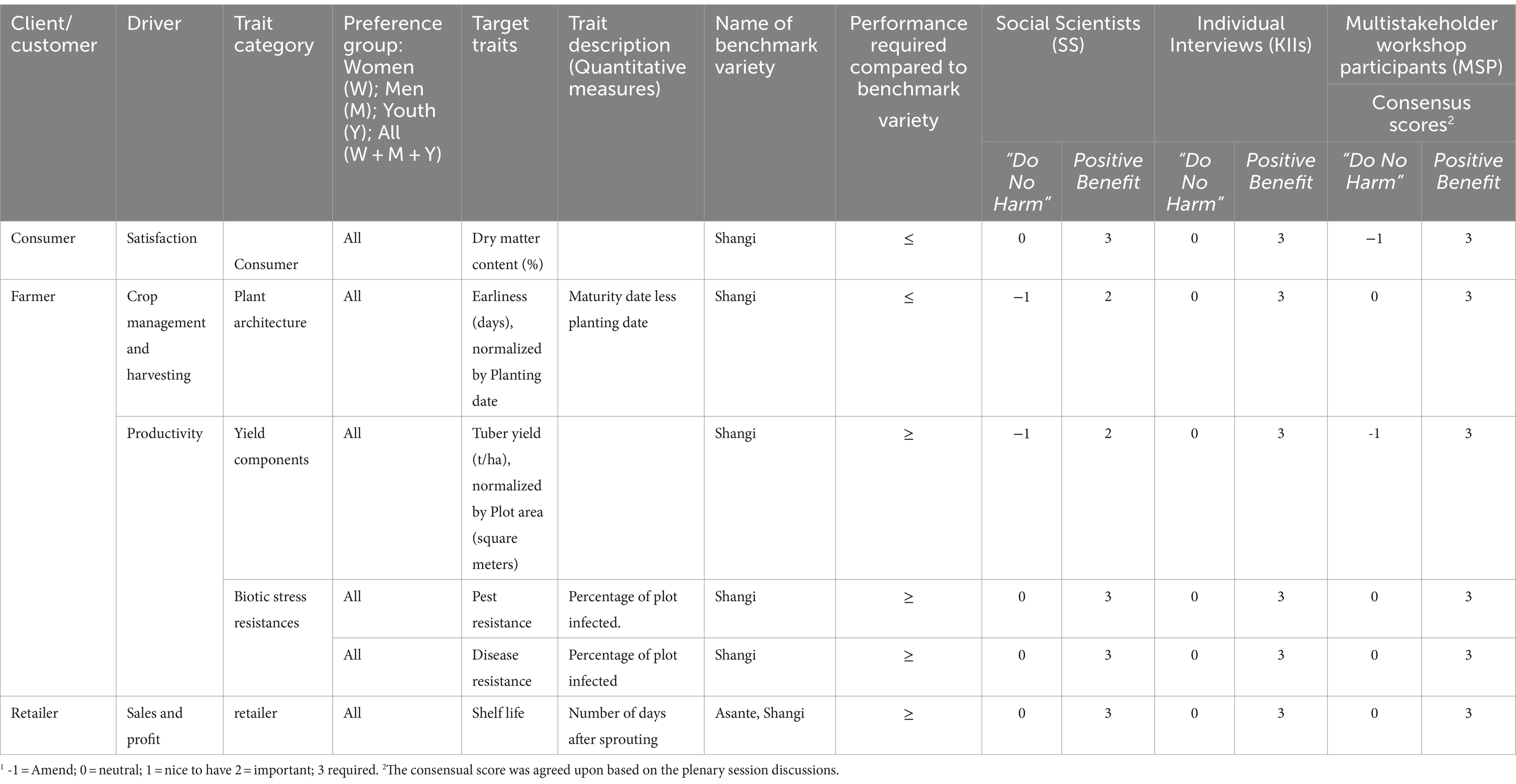

Lastly, the G + PP tool evaluates individual traits included or proposed in a breeder’s target product profile 1 (TPP). As illustrated in Figure 1 , for each trait, the tool generates a gender impact score for ‘Do No Harm” ranging from −2 (reject) to 0 (gender neutral) and another gender impact score for “Positive Benefit” ranging from 0 to +3 (required). Two scores are generated because breeders often weigh trade-offs between the downside and upside of a given trait to decide whether to include the trait in the final TPP. In the “Do no harm” scale, −2 implies an increase in the gender inequality dimensions with serious harm to women and men or households’ wealth and welfare for more than 50% of the target customer segment. A score of −1 shows moderate harm for the majority, and variety release should be accompanied by interventions to remove identified gender inequalities. A score of zero implies that the trait is gender neutral for the “Do no harm” and “Positive benefit” assessments. For the “Positive benefits” scale, a score of +3 is rated as a ‘must have’ trait with benefits with anticipated major improvements for all women and men or household wealth and welfare in a target customer segment. A score of +2 implies significant improvement for the more than 50% of the women. Such a trait is rated to be ‘important’. A score of +1 implies a moderate benefit for most women in the target customer segment and is rated as ‘nice to have’ ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . G+ Product Profile Query tool for “Do no harm” and “Positive benefits”.

3.2 The PASTTA project

We applied the G+ PP tool to assess the table potato TPP developed under the Partnership for Seed Technology Transfer in Africa (PASTTA) project. The PASTTA project is a Global Development Alliance (GDA) between the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Feed the Future initiative and the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture (SFSA). Its main objective was to assist African smallholder farmers in Mali, Senegal, Kenya, Malawi, and Uganda in accessing quality seeds of improved crop varieties to increase their productivity and profit/income. The project targeted seven staple food and cash crops: sorghum, maize, pearl millet, beans, groundnut, soybean, and Irish potato (herein referred to as potato).