An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Service design activities in health services: A systematic literature review based on ecosystem perspective and transformative approach

Affiliations.

- 1 Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, UFRJ, COPPEAD Institute Pascoal Lemme st., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 2 Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, UFRJ Pascoal Lemme st., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 3 São Paulo School of Business Administration, EAESP-FGV Avenida 9 de julho, São Paulo, Brazil.

- PMID: 37547988

- DOI: 10.1002/hpm.3682

Service Design (SD) represents a breakthrough in searching for solutions to health systems challenges, but the activities that support these solutions remain underexplored. This research investigates how SD has been applied in the healthcare sector based on two conceptual models: multilevel ecosystem perspective and SD transformative approach. First, we conducted a systematic literature review in eight comprehensive databases in March 2021. Eligibility criteria returned 990 articles filtered by a search protocol, resulting in 47 studies. After this, we identified 23 studies (49%) with a transformative approach through a thematic analysis. Also, the analysis of these 23 studies allowed the identification of five key aspects necessary for enabling a transformative character of SD initiatives: (1) identification of all the actors that make up the provision of healthcare services, (2) identification of users by ecosystem level, (3) knowledge about the SD tools arsenal, (4) use of technology, and (5) applying the Experience-Based Design and Co-Design (EBD/EBCD) approach. The study underlines the role of management for the success of SD in the health sector and suggests an instrument (checklist) to help managers implement SD initiatives successfully.

Keywords: ecosystem; healthcare; service design; transformative approach.

© 2023 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Service design for the transformation of healthcare systems: A systematic review of literature. Vaz N, Araujo CAS. Vaz N, et al. Health Serv Manage Res. 2023 Aug 8:9514848231194846. doi: 10.1177/09514848231194846. Online ahead of print. Health Serv Manage Res. 2023. PMID: 37553289

- Healthcare workers' perceptions and experiences of primary healthcare integration: a scoping review of qualitative evidence. Moloi H, Daniels K, Brooke-Sumner C, Cooper S, Odendaal WA, Thorne M, Akama E, Leon N. Moloi H, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Jul 11;7(7):CD013603. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013603.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023 Jul 19;7:CD013603. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013603.pub3. PMID: 37434293 Updated. Review.

- Folic acid supplementation and malaria susceptibility and severity among people taking antifolate antimalarial drugs in endemic areas. Crider K, Williams J, Qi YP, Gutman J, Yeung L, Mai C, Finkelstain J, Mehta S, Pons-Duran C, Menéndez C, Moraleda C, Rogers L, Daniels K, Green P. Crider K, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 Feb 1;2(2022):CD014217. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014217. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. PMID: 36321557 Free PMC article.

- A systematic review of social participation in ecosystem services studies in Latin America from a transdisciplinary perspective, 1996-2020. Castro-Díaz R, Delgado LE, Langle-Flores A, Perevochtchikova M, Marín VH. Castro-Díaz R, et al. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Jul 1;828:154523. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154523. Epub 2022 Mar 12. Sci Total Environ. 2022. PMID: 35292319 Review.

- Beyond the black stump: rapid reviews of health research issues affecting regional, rural and remote Australia. Osborne SR, Alston LV, Bolton KA, Whelan J, Reeve E, Wong Shee A, Browne J, Walker T, Versace VL, Allender S, Nichols M, Backholer K, Goodwin N, Lewis S, Dalton H, Prael G, Curtin M, Brooks R, Verdon S, Crockett J, Hodgins G, Walsh S, Lyle DM, Thompson SC, Browne LJ, Knight S, Pit SW, Jones M, Gillam MH, Leach MJ, Gonzalez-Chica DA, Muyambi K, Eshetie T, Tran K, May E, Lieschke G, Parker V, Smith A, Hayes C, Dunlop AJ, Rajappa H, White R, Oakley P, Holliday S. Osborne SR, et al. Med J Aust. 2020 Dec;213 Suppl 11:S3-S32.e1. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50881. Med J Aust. 2020. PMID: 33314144

- Patrício L, Sangiorgi D, Mahr D, Čaić M, Kalantari S, Sundar S. Leveraging service design for healthcare transformation: toward people-centered, integrated, and technology-enabled healthcare systems. J Serv Manag. 2020;31(5):889-909. https://doi.org/10.1108/josm-11-2019-0332

- Berry LL. Service innovation is urgent in healthcare. AMS Rev. 2019;9(1-2):78-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-019-00135-x

- Chamberlain P, Partridge R. Co-designing co-design: shifting the culture of practice in healthcare. Des J. 2017;20(Suppl 1):S2010-S2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352720

- Patrício L, Fisk RP, Falcão e Cunha J, Constantine L. Multilevel service design: from customer value constellation to service experience blueprinting. J Serv Res. 2011;14(2):180-200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511401901

- Eljiiz K, Greenfield D, Vrklevski L, et al. Large scale healthcare facility redevelopment: a scoping review. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2021:1-24.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Service Design

What is service design.

Service design is a process where designers create sustainable solutions and optimal experiences for both customers in unique contexts and any service providers involved. Designers break services into sections and adapt fine-tuned solutions to suit all users’ needs in context—based on actors, location and other factors.

“When you have two coffee shops right next to each other, and each sells the exact same coffee at the exact same price, service design is what makes you walk into one and not the other.” — 31Volts Service Design Studio

See how effective service design can result in more delightful experiences.

- Transcript loading…

Service Design is about Designing for the Biggest Picture

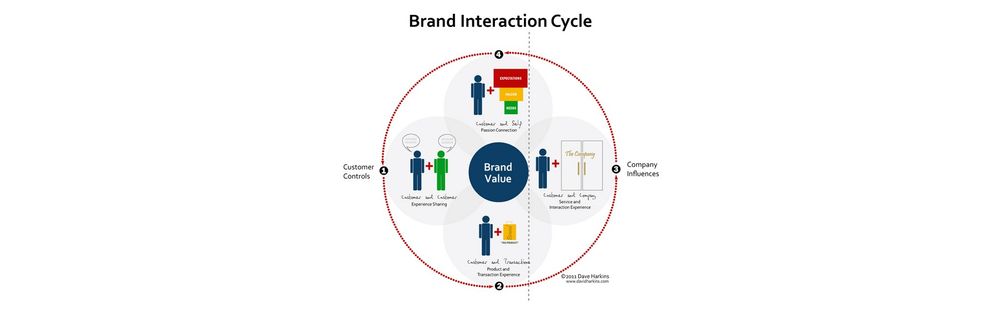

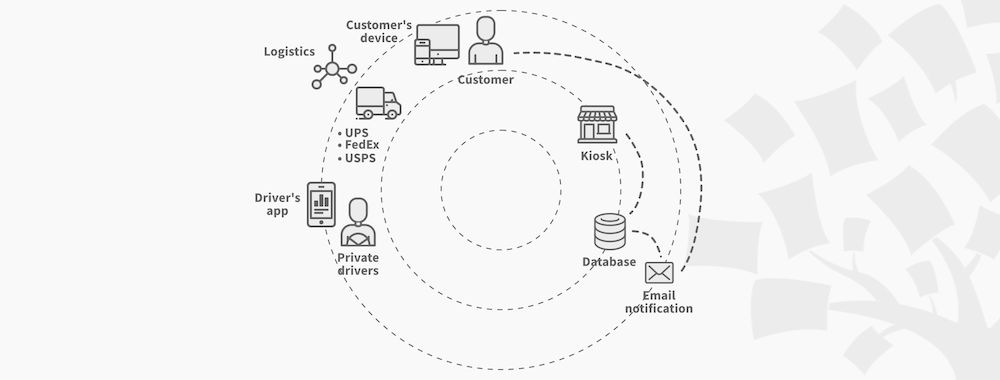

Users don’t access brands in a vacuum, but within complex chains of interactions. For example, a car is a product, but in service design terms it’s a tool when an elderly customer wants to book an Uber ride to visit a friend in hospital. There’s much to consider in such contexts. This user might be accessing Uber on a smartphone, which she’s still learning to use. Perhaps she’s infirm, too, lives in an assisted living facility and must inform the driver about her specific needs. Also, she’s not the only user involved here. Other users are any service providers attached to her user experience. For example, the driver that customer books also uses Uber—but experiences a different aspect of it. To cater to various users’ and customers’ contexts as a designer, you must understand these sorts of relations between service receivers and service providers and the far-reaching aspects of their contexts from start to finish. Only then can you ideate towards solutions for these users’/customers’ specific ecosystems while you ensure brands can deliver on expectations optimally and sustainably .

In service design, you work within a broad scope including user experience (UX) design and customer experience (CX) design . To design for everyone concerned, you must appreciate the macro- and micro-level factors that affect their realities.

A service design experience often involves multiple channels, contexts and products.

Marc Stickdorn and Jakob Schneider, authors of This is Service Design Thinking , identify five key principles—for service design to be:

User-centered – Use qualitative research to design focusing on all users.

Co-creative – Include all relevant stakeholders in the design process.

Sequencing – Break a complex service into separate processes and user journey sections.

Evidencing – Envision service experiences to make them tangible for users to understand and trust brands.

Holistic – Design for all touchpoints throughout experiences, across networks of users and interactions.

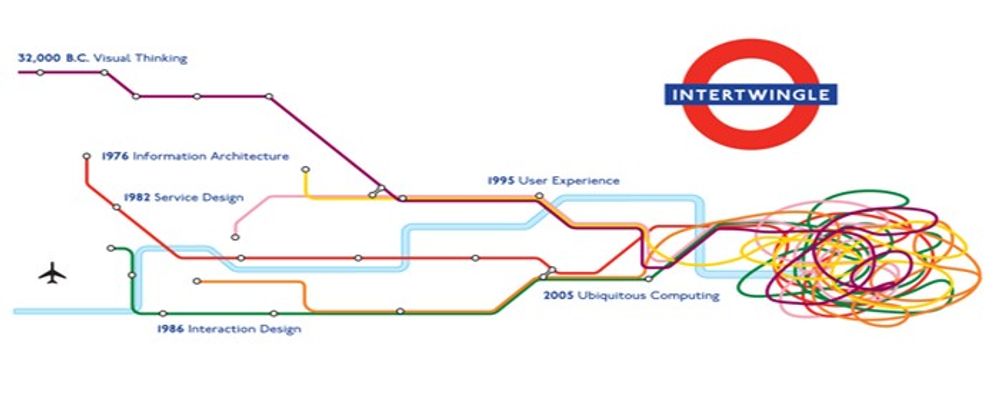

Designers increasingly work more around services than around physical products—e.g., SaaS (software as a service). Meanwhile, with advances in digital technology continually redefining what users can expect whenever they proceed towards goals, brands focus on maximizing convenience and removing barriers for their users . A digital example is Square, which unbundles point-of-sale systems from cash registers and rebundles smartphones as potential point-of-sale systems.

How to Do Service Design Best

First, identify these vital parts of any service encounter:

Actors (e.g., employees delivering the service)

Location (e.g., a virtual environment where customers receive the service)

Props (e.g., objects used during service delivery)

Associates (other organizations involved in providing the service – e.g., logistics)

Processes (e.g., workflows used to deliver the service)

You’ll need to define problems, iterate and address all dimensions of the customers’, users’ and business needs best in a holistic design . To begin, you must empathize with all relevant users/customers. These are some of the most common tools:

Customer journey maps (to find the customers’ touchpoints, barriers and critical moments)

Personas (to help envision target users)

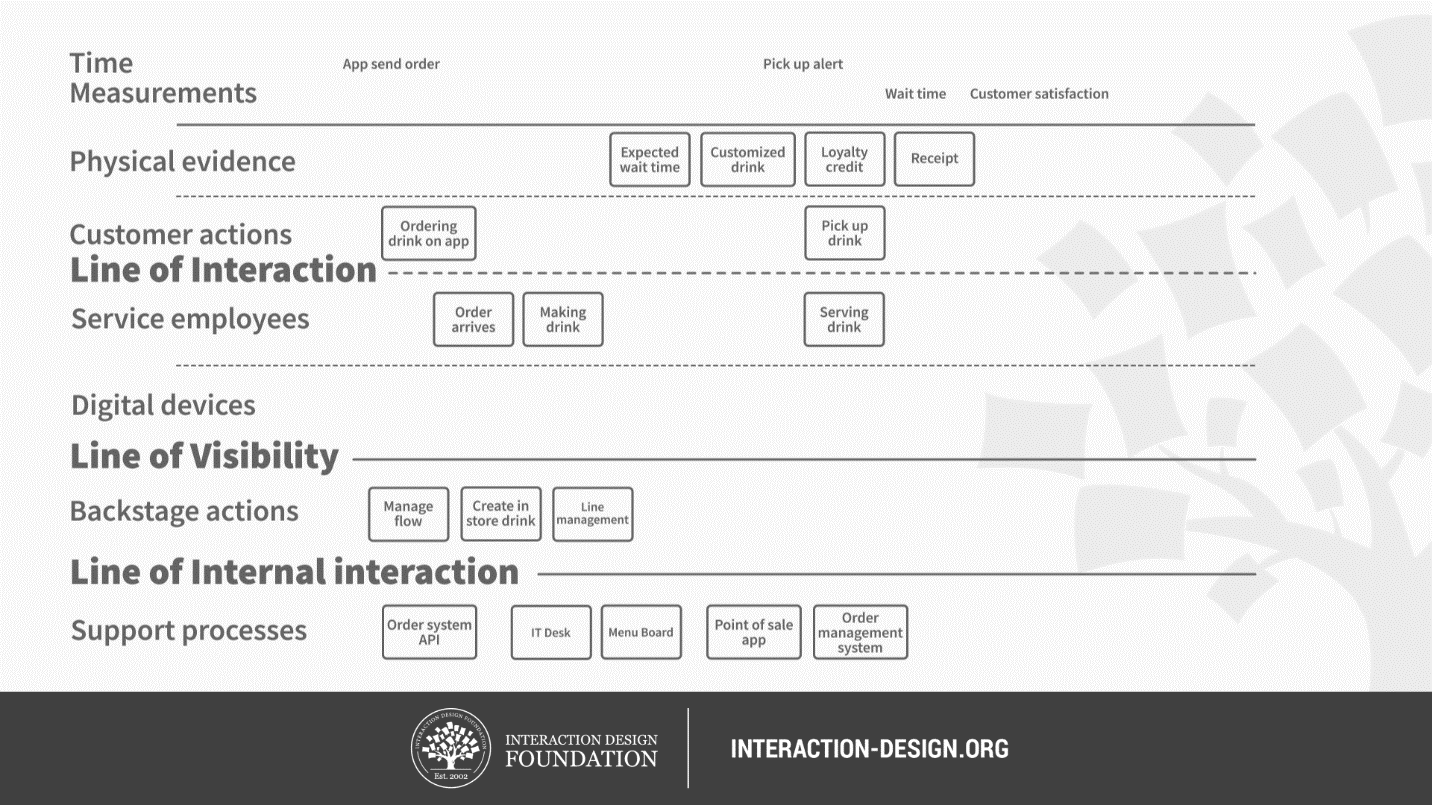

Service blueprints (elevated forms of customer journey maps that help reveal the full spectrum of situations where users/customers can interact with brands)

You should use these to help leverage insights to account for such vital areas as accessibility and customer reengagement.

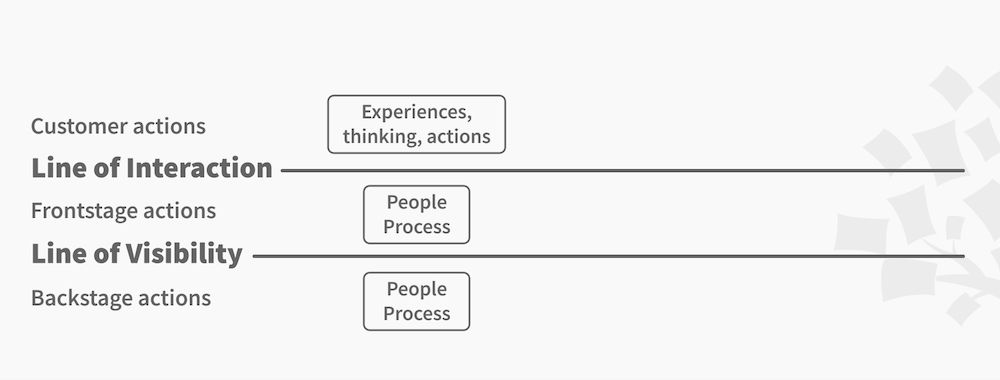

Service blueprints are an important tool in the service design process.

Do Service Design for the Complete Experience

Remember to design for the complete experience. That means you should accommodate your users’/customers’ environment/s and the various barriers, motivations and feelings they’ll have. Here are some core considerations:

Understand your brand’s purpose, the demand for it and the ability of all associated service providers to deliver on promises.

The customers’ needs come ahead of the brand’s internal ones .

Focus on delivering unified and efficient services holistically —as opposed to taking a component-by-component approach.

Include input from users .

Streamline work processes to maximize efficiency .

Co-creation sessions are vital to prototyping .

Eliminate anything (e.g., features, work processes) that fails to add value for customers.

Use agile development to adapt to ever-changing customer needs.

Service design applies both to not-so-tangible areas (e.g., riders buying a single Uber trip) and tangible ones (e.g., iPhone owners visiting Apple Store for assistance/repairs). Overall, service design is a conversation where you should leave your users and customers satisfied at all touchpoints, delighted to have encountered your brand.

Learn More about Service Design

Learn all about service design by taking our course: Service Design: How to Design Integrated Service Experiences .

Read this insightful piece, Service Design: What Is It, What Does It Involve, And Should You Care?

Discover more about service blueprinting in Service Design 101

Read this eye-opening piece exploring Service Design Thinking

Examine Uber’s service design in Uber Service Design Teardown

Questions related to Service Design

A service design diagram is a visual representation of the overall structure and components of a service, including the interactions between different elements. It provides an overview of the service and helps stakeholders understand how different parts of the service fit together. It may include information such as user interfaces, system components, data flows, and more.

Actors/Roles: Entities bringing the experience to the customer.

Information Flow: Details of data shared, required, or used.

Interactions: Between people, systems, and services.

Devices & Channels: Tools and mediums of communication.

The diagram is essential for understanding the current state of a service, emphasizing the intricacies and interdependencies, guiding service blueprint creation, and identifying potential breakpoints or areas for enhancement.

In the context of service design, frontstage refers to the actions performed by employees that are visible to the customer. It includes interactions such as customer service, product demonstrations, and any other activities that customers can directly observe.

On the other hand, backstage actions are performed by employees that are not visible to the customer. These actions support the service delivery and may include tasks such as inventory management, quality control, and other behind-the-scenes operations.

Good service design is a holistic approach that prioritizes every user interaction, both in digital and real-life contexts. Jonas Piet, Director and Service Design Lead at Inwithforward shares the example of Kudoz, a learning platform to demonstrate backstage service design.

While the digital platform is a crucial component, the user's journey begins long before they interact with the app. It might start with discovering the service at a community event or through a promotional video. Service designers ensure that every touchpoint, from community events to the digital interface, provides a coherent and positive experience. They focus on the intricate details, be it designing the role of an 'Experience Curator', crafting a compelling story, or ensuring safety checks. In essence, good service design intertwines various interactions, ensuring they align perfectly.

Discover the principles of human-centered design through Interaction Design Foundation's in-depth courses: Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman offers a contemporary perspective on design thinking, while Design for a Better World with Don Norman emphasizes designing for positive global impact. To deepen your understanding, Don Norman's seminal book, " Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered ," from MIT Press, is an invaluable resource.

Developing service design begins with

In-depth user research, often ethnographic field studies, forming personas and journey maps.

Engage stakeholders early and consistently.

Utilize tools like the business model and value proposition canvases for a strategic foundation.

Transition from journey maps to service blueprints, mapping out the entire service ecosystem.

Embrace prototyping, iteratively refining with stakeholder input.

Thoroughly test prototypes, launch the finalized service, and continuously measure its impact.

Learn more from the video below:

Service design starts by understanding all pieces of an activity, centered on a user's need.

It involves figuring out systems from the ground up to support the experience, considering digital, physical, and social contexts. In-depth user research, stakeholder engagement, and aligning organizational resources, user needs, and outcomes are vital.

Service design, as discussed in our video, encompasses both the visible interactions a customer experiences and the underlying processes staff engage with. It deals with a complex web of interconnectivity, from front-end interactions to back-end systems and distribution. However, the challenge isn't just about designing services. The organizational culture must be receptive. Even if service designers identify areas of improvement, if the organization isn't prepared or faces legislative and technological barriers, change becomes arduous. Despite having dedicated individuals wanting change, they can often be constrained by larger, intricate issues. Service design requires a holistic approach, and while it can pinpoint problems, actual implementation might be held back by factors beyond the design realm.

UX (User Experience) design centers on the digital experience of users, focusing on specific touchpoints (which are often screen-based interactions). CX (Customer Experience) is broader, encompassing every touchpoint a customer has with a brand, from digital to in-store.

Service design has the highest scope of the three concepts, factoring in business processes, systems, and other back-end elements that the customer does not interact with. While UX zooms in on digital interactions, service design steps back, integrating everything for a seamless journey. All three disciplines aim to enhance the user's or customer's experience but operate at different scales and depths.

Absolutely! As businesses increasingly recognize the value of delivering exceptional customer experiences, service design has become a pivotal discipline. It ensures seamless and holistic services that cater to both customer needs and business goals.

- Copyright holder: Matthew Yohe. Appearance time: 0:06 - 0:08 Copyright license and terms: CC-BY-SA-3.0 . Modified: No. Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Steve Jobs Headshot 2010-CROP (cropped_2).jpg

The demand for professionals with expertise in service design is growing across various industries, from tech to hospitality. In order to stay competitive and satisfy the current demand, many individuals are looking to improve their skills. For those keen on mastering this domain, Interaction Design Foundation's course on Service Design provides an in-depth understanding and hands-on learning. It's a great way to get started or deepen your expertise!

Answer a Short Quiz to Earn a Gift

What is the primary goal of service design?

- To create visually appealing service interfaces

- To ensure financial growth for service providers

- To optimize experiences for both customers and service providers

Which principle of service design involves breaking complex services into manageable parts?

- Co-creative

Which tool is an elevated form of a customer journey map to reveal a full spectrum of user interactions with a brand?

- Service blueprints

- User scenarios

What should designers focus on for a complete service experience?

- They should concentrate solely on the technological aspects.

- They should prioritize brand needs over customer needs.

- They should understand and accommodate user environments and barriers.

What is an intended outcome of employing service design in business practices?

- To decrease the overall user base to manage expectations better

- To increase service complexity to enhance user engagement

- To leave users satisfied at all touchpoints with the brand

Better luck next time!

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

Congratulations! You did amazing

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

Check Your Inbox

We’ve emailed your gift to [email protected] .

Literature on Service Design

Here’s the entire UX literature on Service Design by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Service Design

Take a deep dive into Service Design with our course Service Design: How to Design Integrated Service Experiences .

Services are everywhere! When you get a new passport, order a pizza or make a reservation on AirBnB, you're engaging with services. How those services are designed is crucial to whether they provide a pleasant experience or an exasperating one. The experience of a service is essential to its success or failure no matter if your goal is to gain and retain customers for your app or to design an efficient waiting system for a doctor’s office.

In a service design process, you use an in-depth understanding of the business and its customers to ensure that all the touchpoints of your service are perfect and, just as importantly, that your organization can deliver a great service experience every time . It’s not just about designing the customer interactions; you also need to design the entire ecosystem surrounding those interactions.

In this course, you’ll learn how to go through a robust service design process and which methods to use at each step along the way. You’ll also learn how to create a service design culture in your organization and set up a service design team . We’ll provide you with lots of case studies to learn from as well as interviews with top designers in the field. For each practical method, you’ll get downloadable templates that guide you on how to use the methods in your own work.

This course contains a series of practical exercises that build on one another to create a complete service design project . The exercises are optional, but you’ll get invaluable hands-on experience with the methods you encounter in this course if you complete them, because they will teach you to take your first steps as a service designer. What’s equally important is that you can use your work as a case study for your portfolio to showcase your abilities to future employers! A portfolio is essential if you want to step into or move ahead in a career in service design.

Your primary instructor in the course is Frank Spillers . Frank is CXO of award-winning design agency Experience Dynamics and a service design expert who has consulted with companies all over the world. Much of the written learning material also comes from John Zimmerman and Jodi Forlizzi , both Professors in Human-Computer Interaction at Carnegie Mellon University and highly influential in establishing design research as we know it today.

You’ll earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you complete the course. You can highlight it on your resume, CV, LinkedIn profile or on your website.

All open-source articles on Service Design

The principles of service design thinking - building better services.

- 1.3k shares

Service Design - Design is Not Just for Products

The Moment of Truth: Build Desirable Relationships with Users and Customers

Product-Service Hybrids – When Products and Services Become One

- 3 years ago

10 Ideas to Help You Sell UX Work

Making sense of new UX words: A first dictionary for UX Ecosystem Design

- 8 years ago

Understand the Service Design Process

- 2 years ago

Keep These Goals in Mind to Create Successful Service Designs

Learn the Language of Service Design

Top Service Blueprint Templates

Start Your UX Journey: Essential Insights for Success

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

- DOI: 10.1386/adch_00025_1

- Corpus ID: 229519960

Service design approaches and applications in higher education: A thematic literature review

- Marjo Joshi , M. Alavaikko

- Published 1 October 2020

- Art, Design and Communication in Higher Education

4 Citations

A review of service design pedagogy to identify potential added value to product innovation in higher education, digital design in artistic education: an overview of research in the university setting, bibliometric analysis of review on curriculum reform of design history using cnki database, disciplines go digital - developing transdisciplinary study programs that integrate ai with non-it disciplines, 24 references, project-based learning course design: a service design approach, designing a cultural event as an inclusive educational activity, designing for diverse learning: case study of place-based learning in design and technologies pre-service teacher education, educational design and networked learning: patterns, pattern languages and design practice, experiential learning through community co‐design in interior design pedagogy, measuring the value added from service learning in project-based engineering education, student-staff co-creation in higher education: an evidence-informed model to support future design and implementation, designing for service as one way of designing services, service user and carer involvement in students’ classroom learning in higher education, reimagining digital health education: reflections on the possibilities of the storyboarding method, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Systematic review

- Open access

- Published: 24 June 2024

A systematic review of experimentally tested implementation strategies across health and human service settings: evidence from 2010-2022

- Laura Ellen Ashcraft ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9957-0617 1 , 2 ,

- David E. Goodrich 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Joachim Hero 6 ,

- Angela Phares 3 ,

- Rachel L. Bachrach 7 , 8 ,

- Deirdre A. Quinn 3 , 4 ,

- Nabeel Qureshi 6 ,

- Natalie C. Ernecoff 6 ,

- Lisa G. Lederer 5 ,

- Leslie Page Scheunemann 9 , 10 ,

- Shari S. Rogal 3 , 11 na1 &

- Matthew J. Chinman 3 , 4 , 6 na1

Implementation Science volume 19 , Article number: 43 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1958 Accesses

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Studies of implementation strategies range in rigor, design, and evaluated outcomes, presenting interpretation challenges for practitioners and researchers. This systematic review aimed to describe the body of research evidence testing implementation strategies across diverse settings and domains, using the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy to classify strategies and the Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework to classify outcomes.

We conducted a systematic review of studies examining implementation strategies from 2010-2022 and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021235592). We searched databases using terms “implementation strategy”, “intervention”, “bundle”, “support”, and their variants. We also solicited study recommendations from implementation science experts and mined existing systematic reviews. We included studies that quantitatively assessed the impact of at least one implementation strategy to improve health or health care using an outcome that could be mapped to the five evaluation dimensions of RE-AIM. Only studies meeting prespecified methodologic standards were included. We described the characteristics of studies and frequency of implementation strategy use across study arms. We also examined common strategy pairings and cooccurrence with significant outcomes.

Our search resulted in 16,605 studies; 129 met inclusion criteria. Studies tested an average of 6.73 strategies (0-20 range). The most assessed outcomes were Effectiveness ( n =82; 64%) and Implementation ( n =73; 56%). The implementation strategies most frequently occurring in the experimental arm were Distribute Educational Materials ( n =99), Conduct Educational Meetings ( n =96), Audit and Provide Feedback ( n =76), and External Facilitation ( n =59). These strategies were often used in combination. Nineteen implementation strategies were frequently tested and associated with significantly improved outcomes. However, many strategies were not tested sufficiently to draw conclusions.

This review of 129 methodologically rigorous studies built upon prior implementation science data syntheses to identify implementation strategies that had been experimentally tested and summarized their impact on outcomes across diverse outcomes and clinical settings. We present recommendations for improving future similar efforts.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

While many implementation strategies exist, it has been challenging to compare their effectiveness across a wide range of trial designs and practice settings

This systematic review provides a transdisciplinary evaluation of implementation strategies across population, practice setting, and evidence-based interventions using a standardized taxonomy of strategies and outcomes.

Educational strategies were employed ubiquitously; nineteen other commonly used implementation strategies, including External Facilitation and Audit and Provide Feedback, were associated with positive outcomes in these experimental trials.

This review offers guidance for scholars and practitioners alike in selecting implementation strategies and suggests a roadmap for future evidence generation.

Implementation strategies are “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainment of evidence-based practices or programs” (EBPs) [ 1 ]. In 2015, the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study organized a panel of implementation scientists to compile a standardized set of implementation strategy terms and definitions [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. These 73 strategies were then organized into nine “clusters” [ 5 ]. The ERIC taxonomy has been widely adopted and further refined [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. However, much of the evidence for individual or groups of ERIC strategies remains narrowly focused. Prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses have assessed strategy effectiveness, but have generally focused on a specific strategy, (e.g., Audit and Provide Feedback) [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], subpopulation, disease (e.g., individuals living with dementia) [ 16 ], outcome [ 15 ], service setting (e.g., primary care clinics) [ 17 , 18 , 19 ] or geography [ 20 ]. Given that these strategies are intended to have broad applicability, there remains a need to understand how well implementation strategies work across EBPs and settings and the extent to which implementation knowledge is generalizable.

There are challenges in assessing the evidence of implementation strategies across many EBPs, populations, and settings. Heterogeneity in population characteristics, study designs, methods, and outcomes have made it difficult to quantitatively compare which strategies work and under which conditions [ 21 ]. Moreover, there remains significant variability in how researchers operationalize, apply, and report strategies (individually or in combination) and outcomes [ 21 , 22 ]. Still, synthesizing data related to using individual strategies would help researchers replicate findings and better understand possible mediating factors including the cost, timing, and delivery by specific types of health providers or key partners [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Such an evidence base would also aid practitioners with implementation planning such as when and how to deploy a strategy for optimal impact.

Building upon previous efforts, we therefore conducted a systematic review to evaluate the level of evidence supporting the ERIC implementation strategies across a broad array of health and human service settings and outcomes, as organized by the evaluation framework, RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. A secondary aim of this work was to identify patterns in scientific reporting of strategy use that could not only inform reporting standards for strategies but also the methods employed in future. The current study was guided by the following research questions Footnote 1 :

What implementation strategies have been most commonly and rigorously tested in health and human service settings?

Which implementation strategies were commonly paired?

What is the evidence supporting commonly tested implementation strategies?

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P) model [ 29 , 30 , 31 ] to develop and report on the methods for this systematic review (Additional File 1). This study was considered to be non-human subjects research by the RAND institutional review board.

Registration

The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021235592).

Eligibility criteria

This review sought to synthesize evidence for implementation strategies from research studies conducted across a wide range of health-related settings and populations. Inclusion criteria required studies to: 1) available in English; 2) published between January 1, 2010 and September 20, 2022; 3) based on experimental research (excluded protocols, commentaries, conference abstracts, or proposed frameworks); 4) set in a health or human service context (described below); 5) tested at least one quantitative outcome that could be mapped to the RE-AIM evaluation framework [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]; and 6) evaluated the impact of an implementation strategy that could be classified using the ERIC taxonomy [ 2 , 32 ]. We defined health and human service setting broadly, including inpatient and outpatient healthcare settings, specialty clinics, mental health treatment centers, long-term care facilities, group homes, correctional facilities, child welfare or youth services, aging services, and schools, and required that the focus be on a health outcome. We excluded hybrid type I trials that primarily focused on establishing EBP effectiveness, qualitative studies, studies that described implementation barriers and facilitators without assessing implementation strategy impact on an outcome, and studies not meeting standardized rigor criteria defined below.

Information sources

Our three-pronged search strategy included searching academic databases (i.e., CINAHL, PubMed, and Web of Science for replicability and transparency), seeking recommendations from expert implementation scientists, and assessing existing, relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Search strategy

Search terms included “implementation strateg*” OR “implementation intervention*” OR “implementation bundl*” OR “implementation support*.” The search, conducted on September 20, 2022, was limited to English language and publication between 2010 and 2022, similar to other recent implementation science reviews [ 22 ]. This timeframe was selected to coincide with the advent of Implementation Science and when the term “implementation strategy” became conventionally used [ 2 , 4 , 33 ]. A full search strategy can be found in Additional File 2.

Title and abstract screening process

Each study’s title and abstract were read by two reviewers, who dichotomously scored studies on each of the six eligibility criteria described above as yes=1 or no=0, resulting in a score ranging from 1 to 6. Abstracts receiving a six from both reviewers were included in the full text review. Those with only one score of six were adjudicated by a senior member of the team (MJC, SSR, DEG). The study team held weekly meetings to troubleshoot and resolve any ongoing issues noted through the abstract screening process.

Full text screening

During the full text screening process, we reviewed, in pairs, each article that had progressed through abstract screening. Conflicts between reviewers were adjudicated by a senior member of the team for a final inclusion decision (MJC, SSR, DEG).

Review of study rigor

After reviewing published rigor screening tools [ 34 , 35 , 36 ], we developed an assessment of study rigor that was appropriate for the broad range of reviewed implementation studies. Reviewers evaluated studies on the following: 1) presence of a concurrent comparison or control group (=2 for traditional randomized controlled trial or stepped wedge cluster randomized trial and =1 for pseudo-randomized and other studies with concurrent control); 2) EBP standardization by protocol or manual (=1 if present); 3) EBP fidelity tracking (=1 if present); 4) implementation strategy standardization by operational description, standard training, or manual (=1 if present); 5) length of follow-up from full implementation of intervention (=2 for twelve months or longer, =1 for six to eleven months, or =0 for less than six months); and 6) number of sites (=1 for more than one site). Rigor scores ranged from 0 to 8, with 8 indicating the most rigorous. Articles were included if they 1) included a concurrent control group, 2) had an experimental design, and 3) received a score of 7 or 8 from two independent reviewers.

Outside expert consultation

We contacted 37 global implementation science experts who were recognized by our study team as leaders in the field or who were commonly represented among first or senior authors in the included abstracts. We asked each expert for recommendations of publications meeting study inclusion criteria (i.e., quantitatively evaluating the effectiveness of an implementation strategy). Recommendations were recorded and compared to the full abstract list.

Systematic reviews

Eighty-four systematic reviews were identified through the initial search strategy (See Additional File 3). Systematic reviews that examined the effectiveness of implementation strategies were reviewed in pairs for studies that were not found through our initial literature search.

Data abstraction and coding

Data from the full text review were abstracted in pairs, with conflicts resolved by senior team members (DEG, MJC) using a standard Qualtrics abstraction form. The form captured the setting, number of sites and participants studied, evidence-based practice/program of focus, outcomes assessed (based on RE-AIM), strategies used in each study arm, whether the study took place in the U.S. or outside of the U.S., and the findings (i.e., was there significant improvement in the outcome(s)?). We coded implementation strategies used in the Control and Experimental Arms. We defined the Control Arm as receiving the lowest number of strategies (which could mean zero strategies or care as usual) and the Experimental Arm as the most intensive arm (i.e., receiving the highest number of strategies). When studies included multiple Experimental Arms, the Experimental Arm with the least intensive implementation strategy(ies) was classified as “Control” and the Experimental Arm with the most intensive implementation strategy(ies) was classified as the “Experimental” Arm.

Implementation strategies were classified using standard definitions (MJC, SSR, DEG), based on minor modifications to the ERIC taxonomy [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Modifications resulted in 70 named strategies and were made to decrease redundancy and improve clarity. These modifications were based on input from experts, cognitive interview data, and team consensus [ 37 ] (See Additional File 4). Outcomes were then coded into RE-AIM outcome domains following best practices as recommended by framework experts [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. We coded the RE-AIM domain of Effectiveness as either an assessment of the effectiveness of the EBP or the implementation strategy. We did not assess implementation strategy fidelity or effects on health disparities as these are recently adopted reporting standards [ 27 , 28 ] and not yet widely implemented in current publications. Further, we did not include implementation costs as an outcome because reporting guidelines have not been standardized [ 38 , 39 ].

Assessment and minimization of bias

Assessment and minimization of bias is an important component of high-quality systematic reviews. The Cochrane Collaboration guidance for conducting high-quality systematic reviews recommends including a specific assessment of bias for individual studies by assessing the domains of randomization, deviations of intended intervention, missing data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported results (e.g., following a pre-specified analysis plan) [ 40 , 41 ]. One way we addressed bias was by consolidating multiple publications from the same study into a single finding (i.e., N =1), so-as to avoid inflating estimates due to multiple publications on different aspects of a single trial. We also included high-quality studies only, as described above. However, it was not feasible to consistently apply an assessment of bias tool due to implementation science’s broad scope and the heterogeneity of study design, context, outcomes, and variable measurement, etc. For example, most implementation studies reviewed had many outcomes across the RE-AIM framework, with no one outcome designated as primary, precluding assignment of a single score across studies.

We used descriptive statistics to present the distribution of health or healthcare area, settings, outcomes, and the median number of included patients and sites per study, overall and by country (classified as U.S. vs. non-U.S.). Implementation strategies were described individually, using descriptive statistics to summarize the frequency of strategy use “overall” (in any study arm), and the mean number of strategies reported in the Control and Experimental Arms. We additionally described the strategies that were only in the experimental (and not control) arm, defining these as strategies that were “tested” and may have accounted for differences in outcomes between arms.

We described frequencies of pair-wise combinations of implementation strategies in the Experimental Arm. To assess the strength of the evidence supporting implementation strategies that were used in the Experimental Arm, study outcomes were categorized by RE-AIM and coded based on whether the association between use of the strategies resulted in a significantly positive effect (yes=1; no=0). We then created an indicator variable if at least one RE-AIM outcome in the study was significantly positive (yes=1; no=0). We plotted strategies on a graph with quadrants based on the combination of median number of studies in which a strategy appears and the median percent of studies in which a strategy was associated with at least one positive RE-AIM outcome. The upper right quadrant—higher number of studies overall and higher percent of studies with a significant RE-AIM outcome—represents a superior level of evidence. For implementation strategies in the upper right quadrant, we describe each RE-AIM outcome and the proportion of studies which have a significant outcome.

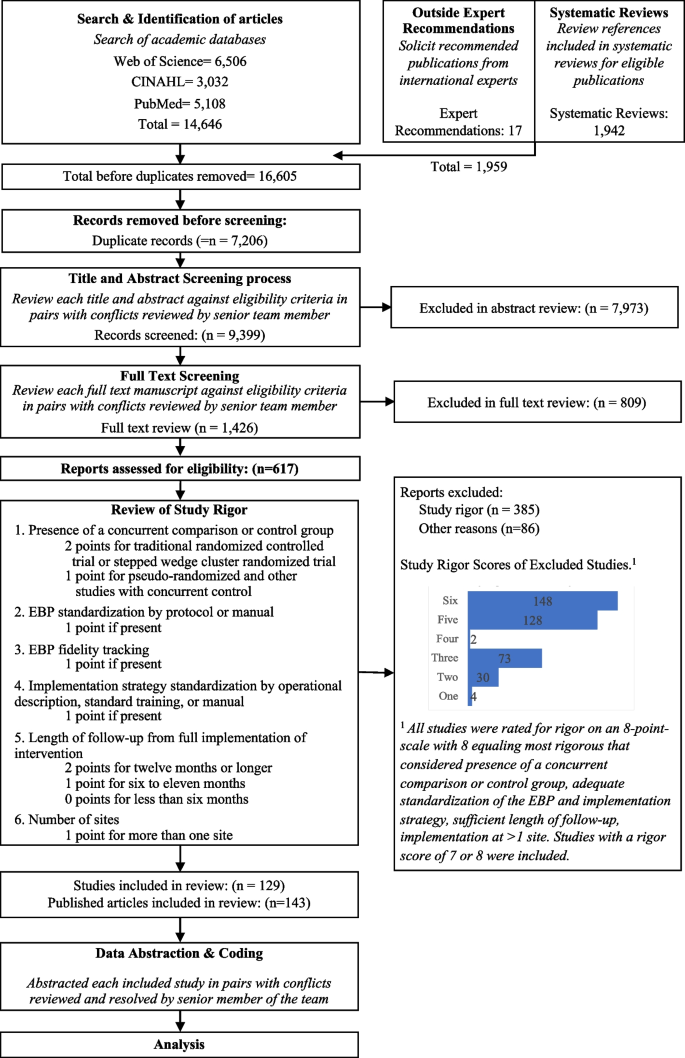

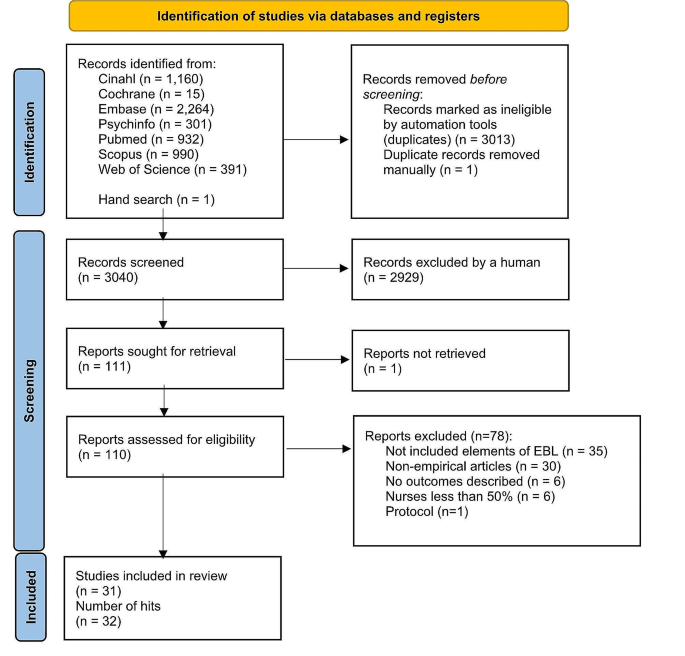

Search results

We identified 14,646 articles through the initial literature search, 17 articles through expert recommendation (three of which were not included in the initial search), and 1,942 articles through reviewing prior systematic reviews (Fig. 1 ). After removing duplicates, 9,399 articles were included in the initial abstract screening. Of those, 48% ( n =4,075) abstracts were reviewed in pairs for inclusion. Articles with a score of five or six were reviewed a second time ( n =2,859). One quarter of abstracts that scored lower than five were reviewed for a second time at random. We screened the full text of 1,426 articles in pairs. Common reasons for exclusion were 1) study rigor, including no clear delineation between the EBP and implementation strategy, 2) not testing an implementation strategy, and 3) article type that did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., commentary, protocol, etc.). Six hundred seventeen articles were reviewed for study rigor with 385 excluded for reasons related to study design and rigor, and 86 removed for other reasons (e.g., not a research article). Among the three additional expert-recommended articles, one met inclusion criteria and was added to the analysis. The final number of studies abstracted was 129 representing 143 publications.

Expanded PRISMA Flow Diagram

The expanded PRISMA flow diagram provides a description of each step in the review and abstraction process for the systematic review

Descriptive results

Of 129 included studies (Table 1 ; see also Additional File 5 for Summary of Included Studies), 103 (79%) were conducted in a healthcare setting. EBP health care setting varied and included primary care ( n =46; 36%), specialty care ( n =27; 21%), mental health ( n =11; 9%), and public health ( n =30; 23%), with 64 studies (50%) occurring in an outpatient health care setting. Studies included a median of 29 sites and 1,419 target population (e.g., patients or students). The number of strategies varied widely across studies, with Control Arms averaging approximately two strategies (Range = 0-20, including studies with no strategy in the comparison group) and Experimental Arms averaging eight strategies (Range = 1-21). Non-US studies ( n =73) included more sites and target population on average, with an overall median of 32 sites and 1,531 patients assessed in each study.

Organized by RE-AIM, the most evaluated outcomes were Effectiveness ( n = 82, 64%) and Implementation ( n = 73, 56%); followed by Maintenance ( n =40; 31%), Adoption ( n =33; 26%), and Reach ( n =31; 24%). Most studies ( n = 98, 76%) reported at least one significantly positive outcome. Adoption and Implementation outcomes showed positive change in three-quarters of studies ( n =78), while Reach ( n =18; 58%), Effectiveness ( n =44; 54%), and Maintenance ( n =23; 58%) outcomes evidenced positive change in approximately half of studies.

The following describes the results for each research question.

Table 2 shows the frequency of studies within which an implementation strategy was used in the Control Arm, Experimental Arm(s), and tested strategies (those used exclusively in the Experimental Arm) grouped by strategy type, as specified by previous ERIC reports [ 2 , 6 ].

Control arm

In about half the studies (53%; n =69), the Control Arms were “active controls” that included at least one strategy, with an average of 1.64 (and up to 20) strategies reported in control arms. The two most common strategies used in Control Arms were: Distribute Educational Materials ( n =52) and Conduct Educational Meetings ( n =30).

Experimental arm

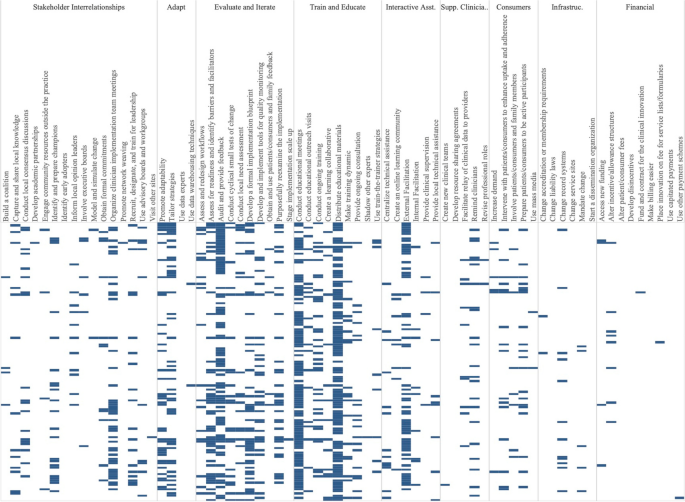

Experimental conditions included an average of 8.33 implementation strategies per study (Range = 1-21). Figure 2 shows a heat map of the strategies that were used in the Experimental Arms in each study. The most common strategies in the Experimental Arm were Distribute Educational Materials ( n =99), Conduct Educational Meetings ( n =96), Audit and Provide Feedback ( n =76), and External Facilitation ( n =59).

Implementation strategies used in the Experimental Arm of included studies. Explore more here: https://public.tableau.com/views/Figure2_16947070561090/Figure2?:language=en-US&:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link

Tested strategies

The average number of implementation strategies that were included in the Experimental Arm only (and not in the Control Arm) was 6.73 (Range = 0-20). Footnote 2 Overall, the top 10% of tested strategies included Conduct Educational Meetings ( n =68), Audit and Provide Feedback ( n =63), External Facilitation ( n =54), Distribute Educational Materials ( n =49), Tailor Strategies ( n =41), Assess for Readiness and Identify Barriers and Facilitators ( n =38) and Organize Clinician Implementation Team Meetings ( n =37). Few studies tested a single strategy ( n =9). These strategies included, Audit and Provide Feedback, Conduct Educational Meetings, Conduct Ongoing Training, Create a Learning Collaborative, External Facilitation ( n =2), Facilitate Relay of Clinical Data To Providers, Prepare Patients/Consumers to be Active Participants, and Use Other Payment Schemes. Three implementation strategies were included in the Control or Experimental Arms but were not Tested including, Use Mass Media, Stage Implementation Scale Up, and Fund and Contract for the Clinical Innovation.

Table 3 shows the five most used strategies in Experimental Arms with their top ten most frequent pairings, excluding Distribute Educational Materials and Conduct Educational Meetings, as these strategies were included in almost all Experimental and half of Control Arms. The five most used strategies in the Experimental Arm included Audit and Provide Feedback ( n =76), External Facilitation ( n =59), Tailor Strategies ( n =43), Assess for Readiness and Identify Barriers and Facilitators ( n =43), and Organize Implementation Teams ( n =42).

Strategies frequently paired with these five strategies included two educational strategies: Distribute Educational Materials and Conduct Educational Meetings. Other commonly paired strategies included Develop a Formal Implementation Blueprint, Promote Adaptability, Conduct Ongoing Training, Purposefully Reexamine the Implementation, and Develop and Implement Tools for Quality Monitoring.

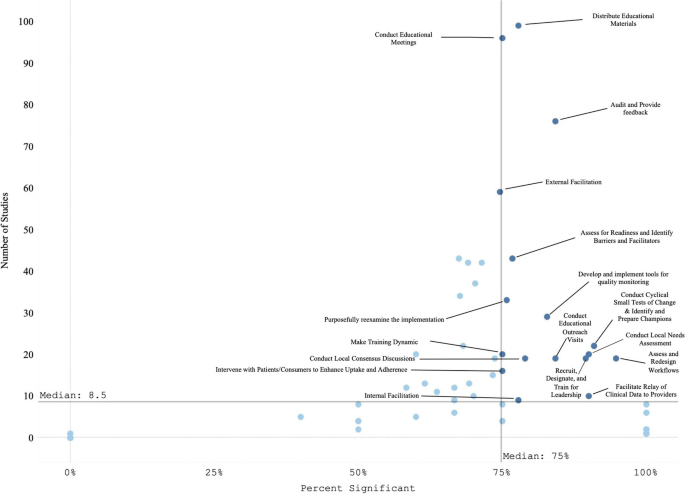

We classified the strength of evidence for each strategy by evaluating both the number of studies in which each strategy appeared in the Experimental Arm and the percentage of times there was at least one significantly positive RE-AIM outcome. Using these factors, Fig. 3 shows the number of studies in which individual strategies were evaluated (on the y axis) compared to the percentage of times that studies including those strategies had at least one positive outcome (on the x axis). Due to the non-normal distribution of both factors, we used the median (rather than the mean) to create four quadrants. Strategies in the lower left quadrant were tested in fewer than the median number of studies (8.5) and were less frequently associated with a significant RE-AIM outcome (75%). The upper right quadrant included strategies that occurred in more than the median number of studies (8.5) and had more than the median percent of studies with a significant RE-AIM outcome (75%); thus those 19 strategies were viewed as having stronger evidence. Of those 19 implementation strategies, Conduct Educational Meetings, Distribute Educational Materials, External Facilitation, and Audit and Provide Feedback continued to occur frequently, appearing in 59-99 studies.

Experimental Arm Implementation Strategies with significant RE-AIM outcome. Explore more here: https://public.tableau.com/views/Figure3_16947017936500/Figure3?:language=en-US&publish=yes&:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link

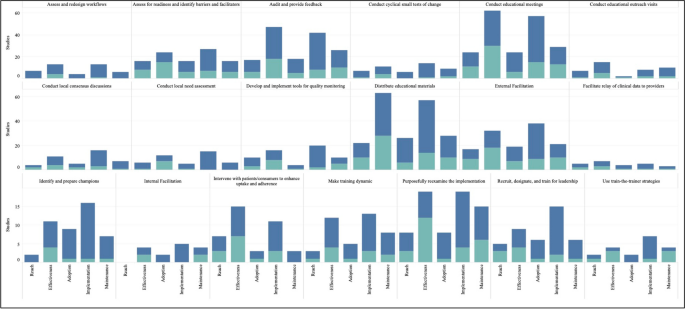

Figure 4 graphically illustrates the proportion of significant outcomes for each RE-AIM outcome for the 19 commonly used and evidence-based implementation strategies in the upper right quadrant. These findings again show the widespread use of Conduct Educational Meetings and Distribute Educational Materials. Implementation and Effectiveness outcomes were assessed most frequently, with Implementation being the mostly commonly reported significantly positive outcome.

RE-AIM outcomes for the 19 Top-Right Quadrant Implementation Strategies . The y-axis is the number of studies and the x-axis is a stacked bar chart for each RE-AIM outcome with R=Reach, E=Effectiveness, A=Adoption, I=Implementation, M=Maintenance. Blue denotes at least one significant RE-AIM outcome; Light blue denotes studies which used the given implementation strategy and did not have a significant RE-AIM . Explore more here: https://public.tableau.com/views/Figure4_16947017112150/Figure4?:language=en-US&publish=yes&:display_count=n&:origin=viz_share_link

This systematic review identified 129 experimental studies examining the effectiveness of implementation strategies across a broad range of health and human service studies. Overall, we found that evidence is lacking for most ERIC implementation strategies, that most studies employed combinations of strategies, and that implementation outcomes, categorized by RE-AIM dimensions, have not been universally defined or applied. Accordingly, other researchers have described the need for universal outcomes definitions and descriptions across implementation research studies [ 28 , 42 ]. Our findings have important implications not only for the current state of the field but also for creating guidance to help investigators determine which strategies and in what context to examine.

The four most evaluated strategies were Distribute Educational Materials, Conduct Educational Meetings, External Facilitation, and Audit and Provide Feedback. Conducting Educational Meetings and Distributing Educational Materials were surprisingly the most common. This may reflect the fact that education strategies are generally considered to be “necessary but not sufficient” for successful implementation [ 43 , 44 ]. Because education is often embedded in interventions, it is critical to define the boundary between the innovation and the implementation strategies used to support the innovation. Further specification as to when these strategies are EBP core components or implementation strategies (e.g., booster trainings or remediation) is needed [ 45 , 46 ].

We identified 19 implementation strategies that were tested in at least 8 studies (more than the median) and were associated with positive results at least 75% of the time. These strategies can be further categorized as being used in early or pre-implementation versus later in implementation. Preparatory activities or pre-implementation, strategies that had strong evidence included educational activities (Meetings, Materials, Outreach visits, Train for Leadership, Use Train the Trainer Strategies) and site diagnostic activities (Assess for Readiness, Identify Barriers and Facilitators, Conduct Local Needs Assessment, Identify and Prepare Champions, and Assess and Redesign Workflows). Strategies that target the implementation phase include those that provide coaching and support (External and Internal Facilitation), involve additional key partners (Intervene with Patients to Enhance Uptake and Adherence), and engage in quality improvement activities (Audit and Provide Feedback, Facilitate the Relay of Clinical Data to Providers, Purposefully Reexamine the Implementation, Conduct Cyclical Small Tests of Change, Develop and Implement Tools for Quality Monitoring).

There were many ERIC strategies that were not represented in the reviewed studies, specifically the financial and policy strategies. Ten strategies were not used in any studies, including: Alter Patient/Consumer Fees, Change Liability Laws, Change Service Sites, Develop Disincentives, Develop Resource Sharing Agreements, Identify Early Adopters, Make Billing Easier, Start a Dissemination Organization, Use Capitated Payments, and Use Data Experts. One of the limitations of this investigation was that not all individual strategies or combinations were investigated. Reasons for the absence of these strategies in our review may include challenges with testing certain strategies experimentally (e.g., changing liability laws), limitations in our search terms, and the relative paucity of implementation strategy trials compared to clinical trials. Many “untested” strategies require large-scale structural changes with leadership support (see [ 47 ] for policy experiment example). Recent preliminary work has assessed the feasibility of applying policy strategies and described the challenges with doing so [ 48 , 49 , 50 ]. While not impossible in large systems like VA (for example: the randomized evaluation of the VA Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Management) the large size, structure, and organizational imperative makes these initiatives challenging to experimentally evaluate. Likewise, the absence of these ten strategies may have been the result of our inclusion criteria, which required an experimental design. Thus, creative study designs may be needed to test high-level policy or financial strategies experimentally.

Some strategies that were likely under-represented in our search strategy included electronic medical record reminders and clinical decision support tools and systems. These are often considered “interventions” when used by clinical trialists and may not be indexed as studies involving ‘implementation strategies’ (these tools have been reviewed elsewhere [ 51 , 52 , 53 ]). Thus, strategies that are also considered interventions in the literature (e.g., education interventions) were not sought or captured. Our findings do not imply that these strategies are ineffective, rather that more study is needed. Consistent with prior investigations [ 54 ], few studies meeting inclusion criteria tested financial strategies. Accordingly, there are increasing calls to track and monitor the effects of financial strategies within implementation science to understand their effectiveness in practice [ 55 , 56 ]. However, experts have noted that the study of financial strategies can be a challenge given that they are typically implemented at the system-level and necessitate research designs for studying policy-effects (e.g., quasi-experimental methods, systems-science modeling methods) [ 57 ]. Yet, there have been some recent efforts to use financial strategies to support EBPs that appear promising [ 58 ] and could be a model for the field moving forward.

The relationship between the number of strategies used and improved outcomes has been described inconsistently in the literature. While some studies have found improved outcomes with a bundle of strategies that were uniquely combined or a standardized package of strategies (e.g., Replicating Effective Programs [ 59 , 60 ] and Getting To Outcomes [ 61 , 62 ]), others have found that “more is not always better” [ 63 , 64 , 65 ]. For example, Rogal and colleagues documented that VA hospitals implementing a new evidence-based hepatitis C treatment chose >20 strategies, when multiple years of data linking strategies to outcomes showed that 1-3 specific strategies would have yielded the same outcome [ 39 ]. Considering that most studies employed multiple or multifaceted strategies, it seems that there is a benefit of using a targeted bundle of strategies that are purposefully aligns with site/clinic/population norms, rather than simply adding more strategies [ 66 ].

It is difficult to assess the effectiveness of any one implementation strategy in bundles where multiple strategies are used simultaneously. Even a ‘single’ strategy like External Facilitation is, in actuality, a bundle of narrowly constructed strategies (e.g., Conduct Educational Meetings, Identify and Prepare Champions, and Develop a Formal Implementation Blueprint). Thus, studying External Facilitation does not allow for a test of the individual strategies that comprise it, potentially masking the effectiveness of any individual strategy. While we cannot easily disaggregate the effects of multifaceted strategies, doing so may not yield meaningful results. Because strategies often synergize, disaggregated results could either underestimate the true impact of individual strategies or conversely, actually undermine their effectiveness (i.e., when their effectiveness comes from their combination with other strategies). The complexity of health and human service settings, imperative to improve public health outcomes, and engagement with community partners often requires the use of multiple strategies simultaneously. Therefore, the need to improve real-world implementation may outweigh the theoretical need to identify individual strategy effectiveness. In situations where it would be useful to isolate the impact of single strategies, we suggest that the same methods for documenting and analyzing the critical components (or core functions) of complex interventions [ 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 ] may help to identify core components of multifaceted implementation strategies [ 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 ].

In addition, to truly assess the impacts of strategies on outcomes, it may be necessary to track fidelity to implementation strategies (not just the EBPs they support). While this can be challenging, without some degree of tracking and fidelity checks, one cannot determine whether a strategy’s apparent failure to work was because it 1) was ineffective or 2) was not applied well. To facilitate this tracking there are pragmatic tools to support researchers. For example, the Longitudinal Implementation Strategy Tracking System (LISTS) offers a pragmatic and feasible means to assess fidelity to and adaptations of strategies [ 75 ].

Implications for implementation science: four recommendations

Based on our findings, we offer four recommended “best practices” for implementation studies.

Prespecify strategies using standard nomenclature. This study reaffirmed the need to apply not only a standard naming convention (e.g., ERIC) but also a standard reporting of for implementation strategies. While reporting systems like those by Proctor [ 1 ] or Pinnock [ 75 ] would optimize learning across studies, few manuscripts specify strategies as recommended [ 76 , 77 ]. Pre-specification allows planners and evaluators to assess the feasibility and acceptability of strategies with partners and community members [ 24 , 78 , 79 ] and allows evaluators and implementers to monitor and measure the fidelity, dose, and adaptations to strategies delivered over the course of implementation [ 27 ]. In turn, these data can be used to assess the costs, analyze their effectiveness [ 38 , 80 , 81 ], and ensure more accurate reporting [ 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 ]. This specification should include, among other data, the intensity, stage of implementation, and justification for the selection. Information regarding why strategies were selected for specific settings would further the field and be of great use to practitioners. [ 63 , 65 , 69 , 79 , 86 ].

Ensure that standards for measuring and reporting implementation outcomes are consistently applied and account for the complexity of implementation studies. Part of improving standardized reporting must include clearly defining outcomes and linking each outcome to particular implementation strategies. It was challenging in the present review to disentangle the impact of the intervention(s) (i.e., the EBP) versus the impact of the implementation strategy(ies) for each RE-AIM dimension. For example, often fidelity to the EBP was reported but not for the implementation strategies. Similarly, Reach and Adoption of the intervention would be reported for the Experimental Arm but not for the Control Arm, prohibiting statistical comparisons of strategies on the relative impact of the EBP between study arms. Moreover, there were many studies evaluating numerous outcomes, risking data dredging. Further, the significant heterogeneity in the ways in which implementation outcomes are operationalized and reported is a substantial barrier to conducting large-scale meta-analytic approaches to synthesizing evidence for implementation strategies [ 67 ]. The field could look to others in the social and health sciences for examples in how to test, validate, and promote a common set of outcome measures to aid in bringing consistency across studies and real-world practice (e.g., the NIH-funded Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System [PROMIS], https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis ).

Develop infrastructure to learn cross-study lessons in implementation science. Data repositories, like those developed by NCI for rare diseases, U.S. HIV Implementation Science Coordination Initiative [ 87 ], and the Behavior Change Technique Ontology [ 88 ], could allow implementation scientists to report their findings in a more standardized manner, which would promote ease of communication and contextualization of findings across studies. For example, the HIV Implementation Science Coordination Initiative requested all implementation projects use common frameworks, developed user friendly databases to enable practitioners to match strategies to determinants, and developed a dashboard of studies that assessed implementation determinants [ 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 ].

Develop and apply methods to rigorously study common strategies and bundles. These findings support prior recommendations for improved empirical rigor in implementation studies [ 46 , 95 ]. Many studies were excluded from our review based on not meeting methodological rigor standards. Understanding the effectiveness of discrete strategies deployed alone or in combination requires reliable and low burden tracking methods to collect information about strategy use and outcomes. For example, frameworks like the Implementation Replication Framework [ 96 ] could help interpret findings across studies using the same strategy bundle. Other tracking approaches may leverage technology (e.g., cell phones, tablets, EMR templates) [ 78 , 97 ] or find novel, pragmatic approaches to collect recommended strategy specifications over time (e.g.., dose, deliverer, and mechanism) [ 1 , 9 , 27 , 98 , 99 ]. Rigorous reporting standards could inform more robust analyses and conclusions (e.g., moving toward the goal of understanding causality, microcosting efforts) [ 24 , 38 , 100 , 101 ]. Such detailed tracking is also required to understand how site-level factors moderate implementation strategy effects [ 102 ]. In some cases, adaptive trial designs like sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMARTs) and just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) can be helpful for planning strategy escalation.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this review, there were certain notable limitations. For one, we only included experimental studies, omitting many informative observational investigations that cover the range of implementation strategies. Second, our study period was centered on the creation of the journal Implementation Science and not on the standardization and operationalization of implementation strategies in the publication of the ERIC taxonomy (which came later). This, in conjunction with latency in reporting study results and funding cycles, means that the employed taxonomy was not applied in earlier studies. To address this limitation, we retroactively mapped strategies to ERIC, but it is possible that some studies were missed. Additionally, indexing approaches used by academic databases may have missed relevant studies. We addressed this particular concern by reviewing other systematic reviews of implementation strategies and soliciting recommendations from global implementation science experts.

Another potential limitation comes from the ERIC taxonomy itself—i.e., strategy listings like ERIC are only useful when they are widely adopted and used in conjunction with guidelines for specifying and reporting strategies [ 1 ] in protocol and outcome papers. Although the ERIC paper has been widely cited (over three thousand times, accessed about 186 thousand times), it is still not universally applied, making tracking the impact of specific strategies more difficult. However, our experience with this review seemed to suggest that ERIC’s use was increasing over time. Also, some have commented that ERIC strategies can be unclear and are missing key domains. Thus, researchers are making definitions clearer for lay users [ 37 , 103 ], increasing the number of discrete strategies for specific domains like HIV treatment, acknowledging strategies for new functions (e.g., de-implementation [ 104 ], local capacity building), accounting for phases of implementation (dissemination, sustainment [ 13 ], scale-up), addressing settings [ 12 , 20 ], actors roles in the process, and making mechanisms of change to select strategies more user-friendly through searchable databases [ 9 , 10 , 54 , 73 , 104 , 105 , 106 ]. In sum, we found the utility of the ERIC taxonomy to outweigh any of the taxonomy’s current limitations.

As with all reviews, the search terms influenced our findings. As such, the broad terms for implementation strategies (e.g., “evidence-based interventions”[ 7 ] or “behavior change techniques” [ 107 ]) may have led to inadvertent omissions of studies of specific strategies. For example, the search terms may not have captured tests of policies, financial strategies, community health promotion initiatives, or electronic medical record reminders, due to differences in terminology used in corresponding subfields of research (e.g., health economics, business, health information technology, and health policy). To manage this, we asked experts to inform us about any studies that they would include and cross-checked their lists with what was identified through our search terms, which yielded very few additional studies. We included standard coding using the ERIC taxonomy, which was a strength, but future work should consider including the additional strategies that have been recommended to augment ERIC, around sustainment [ 13 , 79 , 106 , 108 ], community and public health research [ 12 , 109 , 110 , 111 ], consumer or service user engagement [ 112 ], de-implementation [ 104 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 ] and related terms [ 118 ].

We were unable to assess the bias of studies due to non-standard reporting across the papers and the heterogeneity of study designs, measurement of implementation strategies and outcomes, and analytic approaches. This could have resulted in over- or underestimating the results of our synthesis. We addressed this limitation by being cautious in our reporting of findings, specifically in identifying “effective” implementation strategies. Further, we were not able to gather primary data to evaluate effect sizes across studies in order to systematically evaluate bias, which would be fruitful for future study.

Conclusions

This novel review of 129 studies summarized the body of evidence supporting the use of ERIC-defined implementation strategies to improve health or healthcare. We identified commonly occurring implementation strategies, frequently used bundles, and the strategies with the highest degree of supportive evidence, while simultaneously identifying gaps in the literature. Additionally, we identified several key areas for future growth and operationalization across the field of implementation science with the goal of improved reporting and assessment of implementation strategies and related outcomes.

Availability and materials

All data for this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

We modestly revised the following research questions from our PROSPERO registration after reading the articles and better understanding the nature of the literature: 1) What is the available evidence regarding the effectiveness of implementation strategies in supporting the uptake and sustainment of evidence intended to improve health and healthcare outcomes? 2) What are the current gaps in the literature (i.e., implementation strategies that do not have sufficient evidence of effectiveness) that require further exploration?

Tested strategies are those which exist in the Experimental Arm but not in the Control Arm. Comparative effectiveness or time staggered trials may not have any unique strategies in the Experimental Arm and therefore in our analysis would have no Tested Strategies.

Abbreviations

Centers for Disease Control

Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

Dissemination and Implementation

Evidence-based practices or programs

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

Multiphase Optimization Strategy

National Cancer Institute

National Institutes of Health

The Pittsburgh Dissemination and Implementation Science Collaborative

Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial

United States

Department of Veterans Affairs

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10:21.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, et al. Expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC): protocol for a mixed methods study. Implement Sci IS. 2014;9:39.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Powell BJ, McMillen JC, Proctor EK, Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Bunger AC, et al. A Compilation of Strategies for Implementing Clinical Innovations in Health and Mental Health. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69:123–57.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, Damschroder LJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implement Sci. 2015;10:109.

Perry CK, Damschroder LJ, Hemler JR, Woodson TT, Ono SS, Cohen DJ. Specifying and comparing implementation strategies across seven large implementation interventions: a practical application of theory. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):32.

Community Preventive Services Task Force. Community Preventive Services Task Force: All Active Findings June 2023 [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 7]. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/media/pdf/CPSTF-All-Findings-508.pdf

Solberg LI, Kuzel A, Parchman ML, Shelley DR, Dickinson WP, Walunas TL, et al. A Taxonomy for External Support for Practice Transformation. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2021;34:32–9.

Leeman J, Birken SA, Powell BJ, Rohweder C, Shea CM. Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement Sci. 2017;12:1–9.

Article Google Scholar

Leeman J, Calancie L, Hartman MA, Escoffery CT, Herrmann AK, Tague LE, et al. What strategies are used to build practitioners’ capacity to implement community-based interventions and are they effective?: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:1–15.

Nathan N, Shelton RC, Laur CV, Hailemariam M, Hall A. Editorial: Sustaining the implementation of evidence-based interventions in clinical and community settings. Front Health Serv. 2023;3:1176023.

Balis LE, Houghtaling B, Harden SM. Using implementation strategies in community settings: an introduction to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation and future directions. Transl Behav Med. 2022;12:965–78.

Nathan N, Powell BJ, Shelton RC, Laur CV, Wolfenden L, Hailemariam M, et al. Do the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) strategies adequately address sustainment? Front Health Serv. 2022;2:905909.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259.

Google Scholar

Moore L, Guertin JR, Tardif P-A, Ivers NM, Hoch J, Conombo B, et al. Economic evaluations of audit and feedback interventions: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2022;31:754–67.