Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

Published on February 4, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

A case-control study is an experimental design that compares a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition. Here, the participants possessing the attribute of study, such as a disease, are called the “case,” and those without it are the “control.”

It’s important to remember that the case group is chosen because they already possess the attribute of interest. The point of the control group is to facilitate investigation, e.g., studying whether the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does.

Table of contents

When to use a case-control study, examples of case-control studies, advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Case-control studies are a type of observational study often used in fields like medical research, environmental health, or epidemiology. While most observational studies are qualitative in nature, case-control studies can also be quantitative , and they often are in healthcare settings. Case-control studies can be used for both exploratory and explanatory research , and they are a good choice for studying research topics like disease exposure and health outcomes.

A case-control study may be a good fit for your research if it meets the following criteria.

- Data on exposure (e.g., to a chemical or a pesticide) are difficult to obtain or expensive.

- The disease associated with the exposure you’re studying has a long incubation period or is rare or under-studied (e.g., AIDS in the early 1980s).

- The population you are studying is difficult to contact for follow-up questions (e.g., asylum seekers).

Retrospective cohort studies use existing secondary research data, such as medical records or databases, to identify a group of people with a common exposure or risk factor and to observe their outcomes over time. Case-control studies conduct primary research , comparing a group of participants possessing a condition of interest to a very similar group lacking that condition in real time.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Case-control studies are common in fields like epidemiology, healthcare, and psychology.

You would then collect data on your participants’ exposure to contaminated drinking water, focusing on variables such as the source of said water and the duration of exposure, for both groups. You could then compare the two to determine if there is a relationship between drinking water contamination and the risk of developing a gastrointestinal illness. Example: Healthcare case-control study You are interested in the relationship between the dietary intake of a particular vitamin (e.g., vitamin D) and the risk of developing osteoporosis later in life. Here, the case group would be individuals who have been diagnosed with osteoporosis, while the control group would be individuals without osteoporosis.

You would then collect information on dietary intake of vitamin D for both the cases and controls and compare the two groups to determine if there is a relationship between vitamin D intake and the risk of developing osteoporosis. Example: Psychology case-control study You are studying the relationship between early-childhood stress and the likelihood of later developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here, the case group would be individuals who have been diagnosed with PTSD, while the control group would be individuals without PTSD.

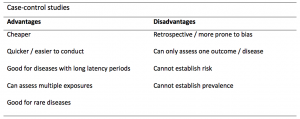

Case-control studies are a solid research method choice, but they come with distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of case-control studies

- Case-control studies are a great choice if you have any ethical considerations about your participants that could preclude you from using a traditional experimental design .

- Case-control studies are time efficient and fairly inexpensive to conduct because they require fewer subjects than other research methods .

- If there were multiple exposures leading to a single outcome, case-control studies can incorporate that. As such, they truly shine when used to study rare outcomes or outbreaks of a particular disease .

Disadvantages of case-control studies

- Case-control studies, similarly to observational studies, run a high risk of research biases . They are particularly susceptible to observer bias , recall bias , and interviewer bias.

- In the case of very rare exposures of the outcome studied, attempting to conduct a case-control study can be very time consuming and inefficient .

- Case-control studies in general have low internal validity and are not always credible.

Case-control studies by design focus on one singular outcome. This makes them very rigid and not generalizable , as no extrapolation can be made about other outcomes like risk recurrence or future exposure threat. This leads to less satisfying results than other methodological choices.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

A case-control study differs from a cohort study because cohort studies are more longitudinal in nature and do not necessarily require a control group .

While one may be added if the investigator so chooses, members of the cohort are primarily selected because of a shared characteristic among them. In particular, retrospective cohort studies are designed to follow a group of people with a common exposure or risk factor over time and observe their outcomes.

Case-control studies, in contrast, require both a case group and a control group, as suggested by their name, and usually are used to identify risk factors for a disease by comparing cases and controls.

A case-control study differs from a cross-sectional study because case-control studies are naturally retrospective in nature, looking backward in time to identify exposures that may have occurred before the development of the disease.

On the other hand, cross-sectional studies collect data on a population at a single point in time. The goal here is to describe the characteristics of the population, such as their age, gender identity, or health status, and understand the distribution and relationships of these characteristics.

Cases and controls are selected for a case-control study based on their inherent characteristics. Participants already possessing the condition of interest form the “case,” while those without form the “control.”

Keep in mind that by definition the case group is chosen because they already possess the attribute of interest. The point of the control group is to facilitate investigation, e.g., studying whether the case group systematically exhibits that attribute more than the control group does.

The strength of the association between an exposure and a disease in a case-control study can be measured using a few different statistical measures , such as odds ratios (ORs) and relative risk (RR).

No, case-control studies cannot establish causality as a standalone measure.

As observational studies , they can suggest associations between an exposure and a disease, but they cannot prove without a doubt that the exposure causes the disease. In particular, issues arising from timing, research biases like recall bias , and the selection of variables lead to low internal validity and the inability to determine causality.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved June 24, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-control-study/

Schlesselman, J. J. (1982). Case-Control Studies: Design, Conduct, Analysis (Monographs in Epidemiology and Biostatistics, 2) (Illustrated). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, control groups and treatment groups | uses & examples, cross-sectional study | definition, uses & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

What Is A Case Control Study?

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A case-control study is a research method where two groups of people are compared – those with the condition (cases) and those without (controls). By looking at their past, researchers try to identify what factors might have contributed to the condition in the ‘case’ group.

Explanation

A case-control study looks at people who already have a certain condition (cases) and people who don’t (controls). By comparing these two groups, researchers try to figure out what might have caused the condition. They look into the past to find clues, like habits or experiences, that are different between the two groups.

The “cases” are the individuals with the disease or condition under study, and the “controls” are similar individuals without the disease or condition of interest.

The controls should have similar characteristics (i.e., age, sex, demographic, health status) to the cases to mitigate the effects of confounding variables .

Case-control studies identify any associations between an exposure and an outcome and help researchers form hypotheses about a particular population.

Researchers will first identify the two groups, and then look back in time to investigate which subjects in each group were exposed to the condition.

If the exposure is found more commonly in the cases than the controls, the researcher can hypothesize that the exposure may be linked to the outcome of interest.

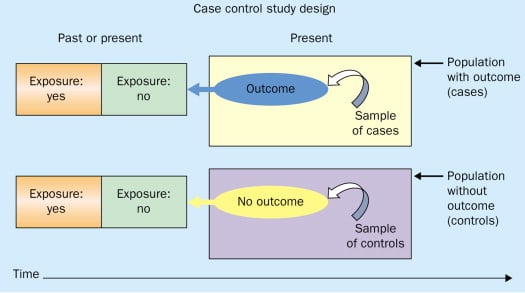

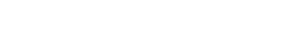

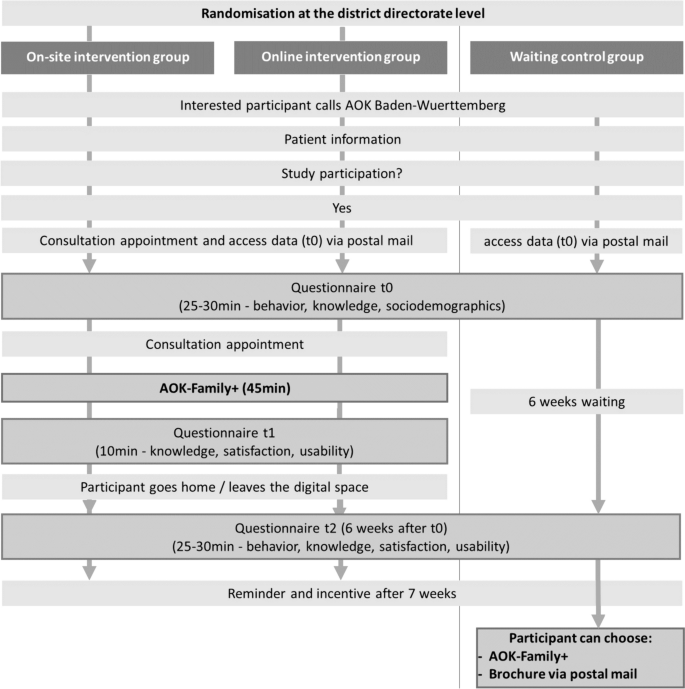

Figure: Schematic diagram of case-control study design. Kenneth F. Schulz and David A. Grimes (2002) Case-control studies: research in reverse . The Lancet Volume 359, Issue 9304, 431 – 434

Quick, inexpensive, and simple

Because these studies use already existing data and do not require any follow-up with subjects, they tend to be quicker and cheaper than other types of research. Case-control studies also do not require large sample sizes.

Beneficial for studying rare diseases

Researchers in case-control studies start with a population of people known to have the target disease instead of following a population and waiting to see who develops it. This enables researchers to identify current cases and enroll a sufficient number of patients with a particular rare disease.

Useful for preliminary research

Case-control studies are beneficial for an initial investigation of a suspected risk factor for a condition. The information obtained from cross-sectional studies then enables researchers to conduct further data analyses to explore any relationships in more depth.

Limitations

Subject to recall bias.

Participants might be unable to remember when they were exposed or omit other details that are important for the study. In addition, those with the outcome are more likely to recall and report exposures more clearly than those without the outcome.

Difficulty finding a suitable control group

It is important that the case group and the control group have almost the same characteristics, such as age, gender, demographics, and health status.

Forming an accurate control group can be challenging, so sometimes researchers enroll multiple control groups to bolster the strength of the case-control study.

Do not demonstrate causation

Case-control studies may prove an association between exposures and outcomes, but they can not demonstrate causation.

A case-control study is an observational study where researchers analyzed two groups of people (cases and controls) to look at factors associated with particular diseases or outcomes.

Below are some examples of case-control studies:

- Investigating the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (Boubekri et al., 2014).

- Comparing serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls (Togha et al., 2018).

- Analyzing correlations between parental smoking and childhood asthma (Strachan and Cook, 1998).

- Studying the relationship between elevated concentrations of homocysteine and an increased risk of vascular diseases (Ford et al., 2002).

- Assessing the magnitude of the association between Helicobacter pylori and the incidence of gastric cancer (Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group, 2001).

- Evaluating the association between breast cancer risk and saturated fat intake in postmenopausal women (Howe et al., 1990).

Frequently asked questions

1. what’s the difference between a case-control study and a cross-sectional study.

Case-control studies are different from cross-sectional studies in that case-control studies compare groups retrospectively while cross-sectional studies analyze information about a population at a specific point in time.

In cross-sectional studies , researchers are simply examining a group of participants and depicting what already exists in the population.

2. What’s the difference between a case-control study and a longitudinal study?

Case-control studies compare groups retrospectively, while longitudinal studies can compare groups either retrospectively or prospectively.

In a longitudinal study , researchers monitor a population over an extended period of time, and they can be used to study developmental shifts and understand how certain things change as we age.

In addition, case-control studies look at a single subject or a single case, whereas longitudinal studies can be conducted on a large group of subjects.

3. What’s the difference between a case-control study and a retrospective cohort study?

Case-control studies are retrospective as researchers begin with an outcome and trace backward to investigate exposure; however, they differ from retrospective cohort studies.

In a retrospective cohort study , researchers examine a group before any of the subjects have developed the disease, then examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

Thus, the outcome is measured after exposure in retrospective cohort studies, whereas the outcome is measured before the exposure in case-control studies.

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611.

Ford, E. S., Smith, S. J., Stroup, D. F., Steinberg, K. K., Mueller, P. W., & Thacker, S. B. (2002). Homocyst (e) ine and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence with special emphasis on case-control studies and nested case-control studies. International journal of epidemiology, 31 (1), 59-70.

Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. (2001). Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut, 49 (3), 347-353.

Howe, G. R., Hirohata, T., Hislop, T. G., Iscovich, J. M., Yuan, J. M., Katsouyanni, K., … & Shunzhang, Y. (1990). Dietary factors and risk of breast cancer: combined analysis of 12 case—control studies. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 82 (7), 561-569.

Lewallen, S., & Courtright, P. (1998). Epidemiology in practice: case-control studies. Community eye health, 11 (28), 57–58.

Strachan, D. P., & Cook, D. G. (1998). Parental smoking and childhood asthma: longitudinal and case-control studies. Thorax, 53 (3), 204-212.

Tenny, S., Kerndt, C. C., & Hoffman, M. R. (2021). Case Control Studies. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540.

Further Information

- Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2002). Case-control studies: research in reverse. The Lancet, 359(9304), 431-434.

- What is a case-control study?

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Case Control Study: Definition, Benefits & Examples

By Jim Frost 2 Comments

What is a Case Control Study?

A case control study is a retrospective, observational study that compares two existing groups. Researchers form these groups based on the existence of a condition in the case group and the lack of that condition in the control group. They evaluate the differences in the histories between these two groups looking for factors that might cause a disease.

By evaluating differences in exposure to risk factors between the case and control groups, researchers can learn which factors are associated with the medical condition.

For example, medical researchers study disease X and use a case-control study design to identify risk factors. They create two groups using available medical records from hospitals. Individuals with disease X are in the case group, while those without it are in the control group. If the case group has more exposure to a risk factor than the control group, that exposure is a potential cause for disease X. However, case-control studies establish only correlation and not causation. Be aware of spurious correlations!

Case-control studies are observational studies because researchers do not control the risk factors—they only observe them. They are retrospective studies because the scientists create the case and control groups after the outcomes for the subjects (e.g., disease vs. no disease) are known.

This post explains the benefits and limitations of case-control studies, controlling confounders, and analyzing and interpreting the results. I close with an example case control study showing how to calculate and interpret the results.

Learn more about Experimental Design: Definition, Types, and Examples .

Related posts : Observational Studies Explained and Control Groups in Experiments

Benefits of a Case Control Study

A case control study is a relatively quick and simple design. They frequently use existing patient data, and the experimenters form the groups after the outcomes are known. Researchers do not conduct an experiment. Instead, they look for differences between the case and control groups that are potential risk factors for the condition. Small groups and individual facilities can conduct case-control studies, unlike other more intensive types of experiments.

Case-control studies are perfect for evaluating outbreaks and rare conditions. Researchers simply need to let a sufficient number of known cases accumulate in an established database. The alternative would be to select a large random sample and hope that the condition afflicts it eventually.

A case control study can provide rapid results during outbreaks where the researchers need quick answers. They are ideal for the preliminary investigation phase, where scientists screen potential risk factors. As such, they can point the way for more thorough, time-consuming, and expensive studies. They are especially beneficial when the current state of science knows little about the connection between risk factors and the medical condition. And when you need to identify potential risk factors quickly!

Cohort studies are another type of observational study that are similar to case-control studies, but there are some important differences. To learn more, read my post about Cohort Studies .

Limitations of a Case Control Study

Because case-control studies are observational, they cannot establish causality and provide lower quality evidence than other experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials . Additionally, as you’ll see in the next section, this type of study is susceptible to confounding variables unless experimenters correctly match traits between the two groups.

A case-control study typically depends on health records. If the necessary data exist in sources available to the researchers, all is good. However, the investigation becomes more complicated if the data are not readily available.

Case-control studies can incorporate biases from the underlying data sources. For example, researchers frequently obtain patient data from hospital records. The population of hospital patients is likely to differ from the general population. Even the control patients are in the hospital for some reason—they likely have serious health problems. Consequently, the subjects in case-control studies are likely to differ from the general population, which reduces the generalizability of the results.

A case-control study cannot estimate incidence or prevalence rates for the disease. The data from these studies do not allow you to calculate the probability of a new person contracting the condition in a given period nor how common it is in the population. This limitation occurs because case-control studies do not use a representative sample.

Case-control studies cannot determine the time between exposure and onset of the medical condition. In fact, case-control studies cannot reliably assess each subject’s exposure to risk factors over time. Longitudinal studies, such as prospective cohort studies, can better make those types of assessment.

Related post : Causation versus Correlation in Statistics

Use Matching to Control Confounders

Because case-control studies are observational studies, they are particularly vulnerable to confounding variables and spurious correlations . A confounder correlates with both the risk factor and the outcome variable. Because observational studies don’t use random assignment to equalize confounders between the case and control groups, they can become unbalanced and affect the results.

Unfortunately, confounders can be the actual cause of the medical condition rather than the risk factor that the researchers identify. If a case-control study does not account for confounding variables, it can bias the results and make them untrustworthy.

Case-control studies typically use trait matching to control confounders. This technique involves selecting study participants for the case and control groups with similar characteristics, which helps equalize the groups for potential confounders. Equalizing confounders limits their impact on the results.

Ultimately, the goal is to create case and control groups that have equal risks for developing the condition/disease outside the risk factors the researchers are explicitly assessing. Matching facilitates valid comparisons between the two groups because the controls are similar to cases. The researchers use subject-area knowledge to identify characteristics that are critical to match.

Note that you cannot assess matching variables as potential risk factors. You’ve intentionally equalized them across the case and control groups and, consequently, they do not correlate with the condition. Hence, do not use the risk factors you want to evaluate as trait matching variables.

Learn more about confounding variables .

Statistical Analysis of a Case Control Study

Researchers frequently include two controls for each case to increase statistical power for a case-control study. Adding even more controls per case provides few statistical benefits, so studies usually do not use more than a 2:1 control to case ratio.

For statistical results, case-control studies typically produce an odds ratio for each potential risk factor. The equation below shows how to calculate an odds ratio for a case-control study.

Notice how this ratio takes the exposure odds in the case group and divides it by the exposure odds in the control group. Consequently, it quantifies how much higher the odds of exposure are among cases than the controls.

In general, odds ratios greater than one flag potential risk factors because they indicate that exposure was higher in the case group than in the control group. Furthermore, higher ratios signify stronger associations between exposure and the medical condition.

An odds ratio of one indicates that exposure was the same in the case and control groups. Nothing to see here!

Ratios less than one might identify protective factors.

Learn more about Understanding Ratios .

Now, let’s bring this to life with an example!

Example Odds Ratio in a Case-Control Study

The Kent County Health Department in Michigan conducted a case-control study in 2005 for a company lunch that produced an outbreak of vomiting and diarrhea. Out of multiple lunch ingredients, researchers found the following exposure rates for lettuce consumption.

| 53 | 33 | |

| 1 | 7 |

By plugging these numbers into the equation, we can calculate the odds ratio for lettuce in this case-control study.

The study determined that the odds ratio for lettuce is 11.2.

This ratio indicates that those with symptoms were 11.2 times more likely to have eaten lettuce than those without symptoms. These results raise a big red flag for contaminated lettuce being the culprit!

Learn more about Odds Ratios.

Epidemiology in Practice: Case-Control Studies (NIH)

Interpreting Results of Case-Control Studies (CDC)

Share this:

Reader Interactions

January 18, 2022 at 7:56 am

Great post, thanks for writing it!

Is it possible to test an odds ration for statistical significance?

January 18, 2022 at 7:41 pm

Hi Michael,

Thanks! And yes, you can test for significance. To learn more about that, read my post about odds ratios , where I discuss p-values and confidence intervals.

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Posted on 6th December 2017 by Saul Crandon

Introduction

Case-control and cohort studies are observational studies that lie near the middle of the hierarchy of evidence . These types of studies, along with randomised controlled trials, constitute analytical studies, whereas case reports and case series define descriptive studies (1). Although these studies are not ranked as highly as randomised controlled trials, they can provide strong evidence if designed appropriately.

Case-control studies

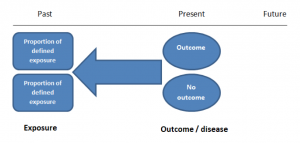

Case-control studies are retrospective. They clearly define two groups at the start: one with the outcome/disease and one without the outcome/disease. They look back to assess whether there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of exposure to a defined risk factor between the groups. See Figure 1 for a pictorial representation of a case-control study design. This can suggest associations between the risk factor and development of the disease in question, although no definitive causality can be drawn. The main outcome measure in case-control studies is odds ratio (OR) .

Figure 1. Case-control study design.

Cases should be selected based on objective inclusion and exclusion criteria from a reliable source such as a disease registry. An inherent issue with selecting cases is that a certain proportion of those with the disease would not have a formal diagnosis, may not present for medical care, may be misdiagnosed or may have died before getting a diagnosis. Regardless of how the cases are selected, they should be representative of the broader disease population that you are investigating to ensure generalisability.

Case-control studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their outcome / disease status.

As such, controls should also be selected carefully. It is possible to match controls to the cases selected on the basis of various factors (e.g. age, sex) to ensure these do not confound the study results. It may even increase statistical power and study precision by choosing up to three or four controls per case (2).

Case-controls can provide fast results and they are cheaper to perform than most other studies. The fact that the analysis is retrospective, allows rare diseases or diseases with long latency periods to be investigated. Furthermore, you can assess multiple exposures to get a better understanding of possible risk factors for the defined outcome / disease.

Nevertheless, as case-controls are retrospective, they are more prone to bias. One of the main examples is recall bias. Often case-control studies require the participants to self-report their exposure to a certain factor. Recall bias is the systematic difference in how the two groups may recall past events e.g. in a study investigating stillbirth, a mother who experienced this may recall the possible contributing factors a lot more vividly than a mother who had a healthy birth.

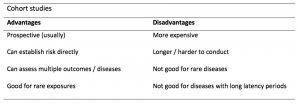

A summary of the pros and cons of case-control studies are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies.

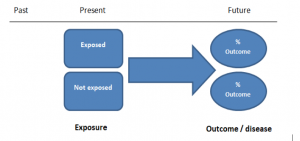

Cohort studies

Cohort studies can be retrospective or prospective. Retrospective cohort studies are NOT the same as case-control studies.

In retrospective cohort studies, the exposure and outcomes have already happened. They are usually conducted on data that already exists (from prospective studies) and the exposures are defined before looking at the existing outcome data to see whether exposure to a risk factor is associated with a statistically significant difference in the outcome development rate.

Prospective cohort studies are more common. People are recruited into cohort studies regardless of their exposure or outcome status. This is one of their important strengths. People are often recruited because of their geographical area or occupation, for example, and researchers can then measure and analyse a range of exposures and outcomes.

The study then follows these participants for a defined period to assess the proportion that develop the outcome/disease of interest. See Figure 2 for a pictorial representation of a cohort study design. Therefore, cohort studies are good for assessing prognosis, risk factors and harm. The outcome measure in cohort studies is usually a risk ratio / relative risk (RR).

Figure 2. Cohort study design.

Cohort studies should include two groups that are identical EXCEPT for their exposure status.

As a result, both exposed and unexposed groups should be recruited from the same source population. Another important consideration is attrition. If a significant number of participants are not followed up (lost, death, dropped out) then this may impact the validity of the study. Not only does it decrease the study’s power, but there may be attrition bias – a significant difference between the groups of those that did not complete the study.

Cohort studies can assess a range of outcomes allowing an exposure to be rigorously assessed for its impact in developing disease. Additionally, they are good for rare exposures, e.g. contact with a chemical radiation blast.

Whilst cohort studies are useful, they can be expensive and time-consuming, especially if a long follow-up period is chosen or the disease itself is rare or has a long latency.

A summary of the pros and cons of cohort studies are provided in Table 2.

The Strengthening of Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement (STROBE)

STROBE provides a checklist of important steps for conducting these types of studies, as well as acting as best-practice reporting guidelines (3). Both case-control and cohort studies are observational, with varying advantages and disadvantages. However, the most important factor to the quality of evidence these studies provide, is their methodological quality.

- Song, J. and Chung, K. Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies . Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.  2010 Dec;126(6):2234-2242.

- Ury HK. Efficiency of case-control studies with multiple controls per case: Continuous or dichotomous data . Biometrics . 1975 Sep;31(3):643–649.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.  Lancet 2007 Oct;370(9596):1453-14577. PMID: 18064739.

Saul Crandon

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Case-control and Cohort studies: A brief overview

Very well presented, excellent clarifications. Has put me right back into class, literally!

Very clear and informative! Thank you.

very informative article.

Thank you for the easy to understand blog in cohort studies. I want to follow a group of people with and without a disease to see what health outcomes occurs to them in future such as hospitalisations, diagnoses, procedures etc, as I have many health outcomes to consider, my questions is how to make sure these outcomes has not occurred before the “exposure disease”. As, in cohort studies we are looking at incidence (new) cases, so if an outcome have occurred before the exposure, I can leave them out of the analysis. But because I am not looking at a single outcome which can be checked easily and if happened before exposure can be left out. I have EHR data, so all the exposure and outcome have occurred. my aim is to check the rates of different health outcomes between the exposed)dementia) and unexposed(non-dementia) individuals.

Very helpful information

Thanks for making this subject student friendly and easier to understand. A great help.

Thanks a lot. It really helped me to understand the topic. I am taking epidemiology class this winter, and your paper really saved me.

Happy new year.

Wow its amazing n simple way of briefing ,which i was enjoyed to learn this.its very easy n quick to pick ideas .. Thanks n stay connected

Saul you absolute melt! Really good work man

am a student of public health. This information is simple and well presented to the point. Thank you so much.

very helpful information provided here

really thanks for wonderful information because i doing my bachelor degree research by survival model

Quite informative thank you so much for the info please continue posting. An mph student with Africa university Zimbabwe.

Thank you this was so helpful amazing

Apreciated the information provided above.

So clear and perfect. The language is simple and superb.I am recommending this to all budding epidemiology students. Thanks a lot.

Great to hear, thank you AJ!

I have recently completed an investigational study where evidence of phlebitis was determined in a control cohort by data mining from electronic medical records. We then introduced an intervention in an attempt to reduce incidence of phlebitis in a second cohort. Again, results were determined by data mining. This was an expedited study, so there subjects were enrolled in a specific cohort based on date(s) of the drug infused. How do I define this study? Thanks so much.

thanks for the information and knowledge about observational studies. am a masters student in public health/epidemilogy of the faculty of medicines and pharmaceutical sciences , University of Dschang. this information is very explicit and straight to the point

Very much helpful

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

Cluster Randomized Trials: Concepts

This blog summarizes the concepts of cluster randomization, and the logistical and statistical considerations while designing a cluster randomized controlled trial.

Expertise-based Randomized Controlled Trials

This blog summarizes the concepts of Expertise-based randomized controlled trials with a focus on the advantages and challenges associated with this type of study.

An introduction to different types of study design

Conducting successful research requires choosing the appropriate study design. This article describes the most common types of designs conducted by researchers.

Study Design 101: Case Control Study

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

A study that compares patients who have a disease or outcome of interest (cases) with patients who do not have the disease or outcome (controls), and looks back retrospectively to compare how frequently the exposure to a risk factor is present in each group to determine the relationship between the risk factor and the disease.

Case control studies are observational because no intervention is attempted and no attempt is made to alter the course of the disease. The goal is to retrospectively determine the exposure to the risk factor of interest from each of the two groups of individuals: cases and controls. These studies are designed to estimate odds.

Case control studies are also known as "retrospective studies" and "case-referent studies."

- Good for studying rare conditions or diseases

- Less time needed to conduct the study because the condition or disease has already occurred

- Lets you simultaneously look at multiple risk factors

- Useful as initial studies to establish an association

- Can answer questions that could not be answered through other study designs

Disadvantages

- Retrospective studies have more problems with data quality because they rely on memory and people with a condition will be more motivated to recall risk factors (also called recall bias).

- Not good for evaluating diagnostic tests because it's already clear that the cases have the condition and the controls do not

- It can be difficult to find a suitable control group

Design pitfalls to look out for

Care should be taken to avoid confounding, which arises when an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable. Controls should be subjects who might have been cases in the study but are selected independent of the exposure. Cases and controls should also not be "over-matched."

Is the control group appropriate for the population? Does the study use matching or pairing appropriately to avoid the effects of a confounding variable? Does it use appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria?

Fictitious Example

There is a suspicion that zinc oxide, the white non-absorbent sunscreen traditionally worn by lifeguards is more effective at preventing sunburns that lead to skin cancer than absorbent sunscreen lotions. A case-control study was conducted to investigate if exposure to zinc oxide is a more effective skin cancer prevention measure. The study involved comparing a group of former lifeguards that had developed cancer on their cheeks and noses (cases) to a group of lifeguards without this type of cancer (controls) and assess their prior exposure to zinc oxide or absorbent sunscreen lotions.

This study would be retrospective in that the former lifeguards would be asked to recall which type of sunscreen they used on their face and approximately how often. This could be either a matched or unmatched study, but efforts would need to be made to ensure that the former lifeguards are of the same average age, and lifeguarded for a similar number of seasons and amount of time per season.

Real-life Examples

Boubekri, M., Cheung, I., Reid, K., Wang, C., & Zee, P. (2014). Impact of windows and daylight exposure on overall health and sleep quality of office workers: a case-control pilot study. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 10 (6), 603-611. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3780

This pilot study explored the impact of exposure to daylight on the health of office workers (measuring well-being and sleep quality subjectively, and light exposure, activity level and sleep-wake patterns via actigraphy). Individuals with windows in their workplaces had more light exposure, longer sleep duration, and more physical activity. They also reported a better scores in the areas of vitality and role limitations due to physical problems, better sleep quality and less sleep disturbances.

Togha, M., Razeghi Jahromi, S., Ghorbani, Z., Martami, F., & Seifishahpar, M. (2018). Serum Vitamin D Status in a Group of Migraine Patients Compared With Healthy Controls: A Case-Control Study. Headache, 58 (10), 1530-1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13423

This case-control study compared serum vitamin D levels in individuals who experience migraine headaches with their matched controls. Studied over a period of thirty days, individuals with higher levels of serum Vitamin D was associated with lower odds of migraine headache.

Related Formulas

- Odds ratio in an unmatched study

- Odds ratio in a matched study

Related Terms

A patient with the disease or outcome of interest.

Confounding

When an exposure and an outcome are both strongly associated with a third variable.

A patient who does not have the disease or outcome.

Matched Design

Each case is matched individually with a control according to certain characteristics such as age and gender. It is important to remember that the concordant pairs (pairs in which the case and control are either both exposed or both not exposed) tell us nothing about the risk of exposure separately for cases or controls.

Observed Assignment

The method of assignment of individuals to study and control groups in observational studies when the investigator does not intervene to perform the assignment.

Unmatched Design

The controls are a sample from a suitable non-affected population.

Now test yourself!

1. Case Control Studies are prospective in that they follow the cases and controls over time and observe what occurs.

a) True b) False

2. Which of the following is an advantage of Case Control Studies?

a) They can simultaneously look at multiple risk factors. b) They are useful to initially establish an association between a risk factor and a disease or outcome. c) They take less time to complete because the condition or disease has already occurred. d) b and c only e) a, b, and c

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- Case Reports

- << Previous: Case Report

- Next: Cohort Study >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A Practical Overview of Case-Control Studies in Clinical Practice

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH; Center for Surgery and Public Health, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH; Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Case Western Reserve University, School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH.

- 3 Department of Statistics, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

- PMID: 32658653

- DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.009

Case-control studies are one of the major observational study designs for performing clinical research. The advantages of these study designs over other study designs are that they are relatively quick to perform, economical, and easy to design and implement. Case-control studies are particularly appropriate for studying disease outbreaks, rare diseases, or outcomes of interest. This article describes several types of case-control designs, with simple graphical displays to help understand their differences. Study design considerations are reviewed, including sample size, power, and measures associated with risk factors for clinical outcomes. Finally, we discuss the advantages and disadvantages of case-control studies and provide a checklist for authors and a framework of considerations to guide reviewers' comments.

Keywords: OR; case-cohort; case-crossover; matching; nested case-control; relative risk.

Copyright © 2020 American College of Chest Physicians. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Study Types in Orthopaedics Research: Is My Study Design Appropriate for the Research Question? Zaniletti I, Devick KL, Larson DR, Lewallen DG, Berry DJ, Maradit Kremers H. Zaniletti I, et al. J Arthroplasty. 2022 Oct;37(10):1939-1944. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.05.028. Epub 2022 Sep 6. J Arthroplasty. 2022. PMID: 36162926 Free PMC article.

- Database Research for Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Kronman MP, Gerber JS, Newland JG, Hersh AL. Kronman MP, et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015 Jun;4(2):143-50. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piv007. Epub 2015 Mar 5. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2015. PMID: 26407414 Review.

- Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Thiese MS. Thiese MS. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2014;24(2):199-210. doi: 10.11613/BM.2014.022. Epub 2014 Jun 15. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2014. PMID: 24969913 Free PMC article. Review.

- [Hybrid designs in studies]. Mandiracioğlu A. Mandiracioğlu A. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009;33(3):227-31. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2009. PMID: 19851970 Turkish.

- Review of guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. Philips Z, Ginnelly L, Sculpher M, Claxton K, Golder S, Riemsma R, Woolacoot N, Glanville J. Philips Z, et al. Health Technol Assess. 2004 Sep;8(36):iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-158. doi: 10.3310/hta8360. Health Technol Assess. 2004. PMID: 15361314 Review.

- Factors Associated with Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury During Vacuum-Assisted Vaginal Delivery. Chill HH, Dick A, Zarka W, Vilk Ayalon N, Rosenbloom JI, Shveiky D, Karavani G. Chill HH, et al. Int Urogynecol J. 2024 May 4. doi: 10.1007/s00192-024-05785-5. Online ahead of print. Int Urogynecol J. 2024. PMID: 38703223

- Association between statin use and the risk for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and its prognosis: a nationwide, population-based study. Park J, Lee CH, Han K, Choi SM. Park J, et al. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 2;14(1):7805. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-58417-9. Sci Rep. 2024. PMID: 38565856 Free PMC article.

- Letter to the Editor: Cross-Sectional Study for Investigation of the Association Between Modifiable Risk Factors and Gastrointestinal Cancers at a Tertiary Hospital in Ghana. Kumar A, Mansoor J, Sadiq H. Kumar A, et al. Cancer Control. 2024 Jan-Dec;31:10732748241233957. doi: 10.1177/10732748241233957. Cancer Control. 2024. PMID: 38365572 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

- Tasks and Experiences of the Prospective, Longitudinal, Multicenter MoMar (Molecular Markers) Study for the Early Detection of Mesothelioma in Individuals Formerly Exposed to Asbestos Using Liquid Biopsies. Weber DG, Casjens S, Wichert K, Lehnert M, Taeger D, Rihs HP, Brüning T, Johnen G, The MoMar Study Group. Weber DG, et al. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Dec 18;15(24):5896. doi: 10.3390/cancers15245896. Cancers (Basel). 2023. PMID: 38136442 Free PMC article.

- How to use the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data: research design and methodology. Che WQ, Li YJ, Tsang CK, Wang YJ, Chen Z, Wang XY, Xu AD, Lyu J. Che WQ, et al. Mil Med Res. 2023 Oct 31;10(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s40779-023-00488-2. Mil Med Res. 2023. PMID: 37899480 Free PMC article. Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Quantitative study designs: Case Control

Quantitative study designs.

- Introduction

- Cohort Studies

- Randomised Controlled Trial

Case Control

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Study Designs Home

In a Case-Control study there are two groups of people: one has a health issue (Case group), and this group is “matched” to a Control group without the health issue based on characteristics like age, gender, occupation. In this study type, we can look back in the patient’s histories to look for exposure to risk factors that are common to the Case group, but not the Control group. It was a case-control study that demonstrated a link between carcinoma of the lung and smoking tobacco . These studies estimate the odds between the exposure and the health outcome, however they cannot prove causality. Case-Control studies might also be referred to as retrospective or case-referent studies.

Stages of a Case-Control study

This diagram represents taking both the case (disease) and the control (no disease) groups and looking back at their histories to determine their exposure to possible contributing factors. The researchers then determine the likelihood of those factors contributing to the disease.

(FOR ACCESSIBILITY: A case control study is likely to show that most, but not all exposed people end up with the health issue, and some unexposed people may also develop the health issue)

Which Clinical Questions does Case-Control best answer?

Case-Control studies are best used for Prognosis questions.

For example: Do anticholinergic drugs increase the risk of dementia in later life? (See BMJ Case-Control study Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study )

What are the advantages and disadvantages to consider when using Case-Control?

* Confounding occurs when the elements of the study design invalidate the result. It is usually unintentional. It is important to avoid confounding, which can happen in a few ways within Case-Control studies. This explains why it is lower in the hierarchy of evidence, superior only to Case Studies.

What does a strong Case-Control study look like?

A strong study will have:

- Well-matched controls, similar background without being so similar that they are likely to end up with the same health issue (this can be easier said than done since the risk factors are unknown).

- Detailed medical histories are available, reducing the emphasis on a patient’s unreliable recall of their potential exposures.

What are the pitfalls to look for?

- Poorly matched or over-matched controls. Poorly matched means that not enough factors are similar between the Case and Control. E.g. age, gender, geography. Over-matched conversely means that so many things match (age, occupation, geography, health habits) that in all likelihood the Control group will also end up with the same health issue! Either of these situations could cause the study to become ineffective.

- Selection bias: Selection of Controls is biased. E.g. All Controls are in the hospital, so they’re likely already sick, they’re not a true sample of the wider population.

- Cases include persons showing early symptoms who never ended up having the illness.

Critical appraisal tools

To assist with critically appraising case control studies there are some tools / checklists you can use.

CASP - Case Control Checklist

JBI – Critical appraisal checklist for case control studies

CEBMA – Centre for Evidence Based Management – Critical appraisal questions (focus on leadership and management)

STROBE - Observational Studies checklists includes Case control

SIGN - Case-Control Studies Checklist

Real World Examples

Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report

- Doll, R., & Hill, A. B. (1950). Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. British Medical Journal , 2 (4682), 739–748. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2038856/

- Key Case-Control study linking tobacco smoking with lung cancer

- Notes a marked increase in incidence of Lung Cancer disproportionate to population growth.

- 20 London Hospitals contributed current Cases of lung, stomach, colon and rectum cancer via admissions, house-physician and radiotherapy diagnosis, non-cancer Controls were selected at each hospital of the same-sex and within 5 year age group of each.

- 1732 Cases and 743 Controls were interviewed for social class, gender, age, exposure to urban pollution, occupation and smoking habits.

- It was found that continued smoking from a younger age and smoking a greater number of cigarettes correlated with incidence of lung cancer.

Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study

- Richardson, K., Fox, C., Maidment, I., Steel, N., Loke, Y. K., Arthur, A., . . . Savva, G. M. (2018). Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. BMJ , 361, k1315. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1315.abstract .

- A recent study linking the duration and level of exposure to Anticholinergic drugs and subsequent onset of dementia.

- Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden (ACB) was estimated in various drugs, the higher the exposure (measured as the ACB score) the greater likeliness of onset of dementia later in life.

- Antidepressant, urological, and antiparkinson drugs with an ACB score of 3 increased the risk of dementia. Gastrointestinal drugs with an ACB score of 3 were not strongly linked with onset of dementia.

- Tricyclic antidepressants such as Amitriptyline have an ACB score of 3 and are an example of a common area of concern.

Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case-Control study

- Rees, A.-M., Austin, M.-P., Owen, C., & Parker, G. (2009). Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case control study. Psychiatry Research , 166(2), 254-259. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178107004398 .

- During pregnancy women lose Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids to the developing foetus.

- There is a known link between Omgea-3 depletion and depression

- Sixteen depressed and 22 non-depressed women were recruited during their third trimester

- High levels of Omega-3 were associated with significantly lower levels of depression.

- Women with low levels of Omega-3 were six times more likely to be depressed during pregnancy.

References and Further Reading

Doll, R., & Hill, A. B. (1950). Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. British Medical Journal, 2(4682), 739–748. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2038856/

Greenhalgh, Trisha. How to Read a Paper: the Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/deakin/detail.action?docID=1642418 .

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. (2019). Study Design 101: Case-Control Study. Retrieved from https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu/tutorials/studydesign101/casecontrols.cfm

Hoffmann, T., Bennett, S., & Del Mar, C. (2017). Evidence-Based Practice Across the Health Professions (Third edition. ed.): Elsevier.

Lewallen, S., & Courtright, P. (1998). Epidemiology in practice: case-control studies. Community Eye Health, 11(28), 57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1706071/

Pelham, B. W. a., & Blanton, H. (2013). Conducting research in psychology : measuring the weight of smoke /Brett W. Pelham, Hart Blanton (Fourth edition. ed.): Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Rees, A.-M., Austin, M.-P., Owen, C., & Parker, G. (2009). Omega-3 deficiency associated with perinatal depression: Case control study. Psychiatry Research, 166(2), 254-259. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178107004398

Richardson, K., Fox, C., Maidment, I., Steel, N., Loke, Y. K., Arthur, A., … Savva, G. M. (2018). Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: case-control study. BMJ, 361, k1315. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/361/bmj.k1315.abstract

Statistics How To. (2019). Case-Control Study: Definition, Real Life Examples. Retrieved from https://www.statisticshowto.com/case-control-study/

- << Previous: Randomised Controlled Trial

- Next: Cross-Sectional Studies >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 10:34 AM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

Case-Control Studies

- 1

- | 2

- | 3

- | 4

- | 5

- | 6

- | 7

- | 8

Selecting & Defining Cases and Controls

The "case" definition, sources of cases, selection of the controls.

E pi_Tools.XLSX

All Modules

Careful thought should be given to the case definition to be used. If the definition is too broad or vague, it is easier to capture people with the outcome of interest, but a loose case definition will also capture people who do not have the disease. On the other hand, an overly restrictive case definition is employed, fewer cases will be captured, and the sample size may be limited. Investigators frequently wrestle with this problem during outbreak investigations. Initially, they will often use a somewhat broad definition in order to identify potential cases. However, as an outbreak investigation progresses, there is a tendency to narrow the case definition to make it more precise and specific, for example by requiring confirmation of the diagnosis by laboratory testing. In general, investigators conducting case-control studies should thoughtfully construct a definition that is as clear and specific as possible without being overly restrictive.

Investigators studying chronic diseases generally prefer newly diagnosed cases, because they tend to be more motivated to participate, may remember relevant exposures more accurately, and because it avoids complicating factors related to selection of longer duration (i.e., prevalent) cases. However, it is sometimes impossible to have an adequate sample size if only recent cases are enrolled.

Typical sources for cases include:

- Patient rosters at medical facilities

- Death certificates

- Disease registries (e.g., cancer or birth defect registries; the SEER Program [Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results] is a federally funded program that identifies newly diagnosed cases of cancer in population-based registries across the US )

- Cross-sectional surveys (e.g., NHANES, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey)

As noted above, it is always useful to think of a case-control study as being nested within some sort of a cohort, i.e., a source population that produced the cases that were identified and enrolled. In view of this there are two key principles that should be followed in selecting controls:

- The comparison group ("controls") should be representative of the source population that produced the cases.

- The "controls" must be sampled in a way that is independent of the exposure, meaning that their selection should not be more (or less) likely if they have the exposure of interest.

If either of these principles are not adhered to, selection bias can result (as discussed in detail in the module on Bias ).

Note that in the earlier example of a case-control study conducted in the Massachusetts population, we specified that our sampling method was random so that exposed and unexposed members of the population had an equal chance of being selected. Therefore, we would expect that about 1,000 would be exposed and 5,000 unexposed (the same ratio as in the whole population), and came up with an odds ratio that was same as the hypothetical risk ratio we would have had if we had collected exposure information from the whole population of six million:

What if we had instead been more likely to sample those who were exposed, so that we instead found 1,500 exposed and 4,500 unexposed among the 6,000 controls? Then the odds ratio would have been:

This odds ratio is biased because it differs from the true odds ratio. In this case, the bias stemmed from the fact that we violated the second principle in selection of controls. Depending on which category is over or under-sampled, this type of bias can result in either an underestimate or an overestimate of the true association.

A hypothetical case-control study was conducted to determine whether lower socioeconomic status (the exposure) is associated with a higher risk of cervical cancer (the outcome). The "cases" consisted of 250 women with cervical cancer who were referred to Massachusetts General Hospital for treatment for cervical cancer. They were referred from all over the state. The cases were asked a series of questions relating to socioeconomic status (household income, employment, education, etc.). The investigators identified control subjects by going door-to-door in the community around MGH from 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. Many residents are not home, but they persist and eventually enroll enough controls. The problem is that the controls were selected by a different mechanism than the cases, AND the selection mechanism may have tended to select individuals of different socioeconomic status, since women who were at home may have been somewhat more likely to be unemployed. In other words, the controls were more likely to be enrolled (selected) if they had the exposure of interest (lower socioeconomic status).

What is the purpose of the control group in a case-control study?

a. To provide information on the disease distribution in the population that gave rise to the cases.

b. To provide information on the exposure distribution in the population that gave rise to the cases.

return to top | previous page | next page

Content ©2016. All Rights Reserved. Date last modified: June 7, 2016. Wayne W. LaMorte, MD, PhD, MPH

- Open access

- Published: 26 June 2024

Characterization of bacterial and viral pathogens in the respiratory tract of children with HIV-associated chronic lung disease: a case–control study

- Prince K. Mushunje 1 na1 ,

- Felix S. Dube 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Courtney Olwagen 3 ,

- Shabir Madhi 3 , 4 ,

- Jon Ø Odland 5 , 6 , 7 ,

- Rashida A. Ferrand 8 , 9 ,

- Mark P. Nicol 10 ,

- Regina E. Abotsi 1 , 11 &

The BREATHE study team

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 24 , Article number: 637 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

175 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction

Chronic lung disease is a major cause of morbidity in African children with HIV infection; however, the microbial determinants of HIV-associated chronic lung disease (HCLD) remain poorly understood. We conducted a case–control study to investigate the prevalence and densities of respiratory microbes among pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV)-naive children with (HCLD +) and without HCLD (HCLD-) established on antiretroviral treatment (ART).

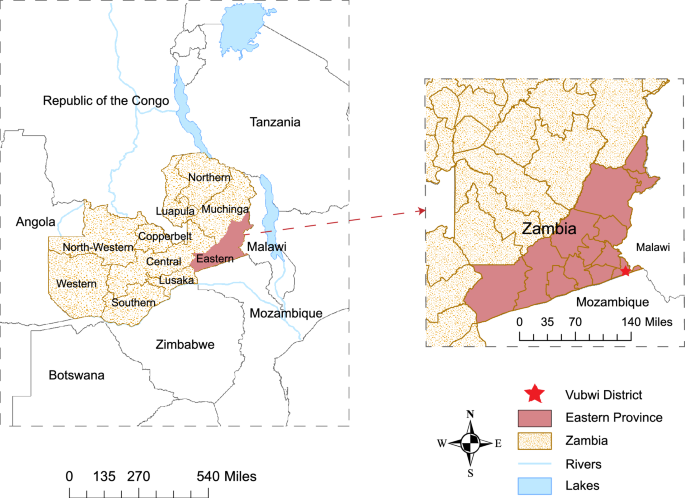

Nasopharyngeal swabs collected from HCLD + (defined as forced-expiratory-volume/second < -1.0 without reversibility postbronchodilation) and age-, site-, and duration-of-ART-matched HCLD- participants aged between 6–19 years enrolled in Zimbabwe and Malawi (BREATHE trial-NCT02426112) were tested for 94 pneumococcal serotypes together with twelve bacteria, including Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP), Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Haemophilus influenzae (HI), Moraxella catarrhalis (MC), and eight viruses, including human rhinovirus (HRV), respiratory syncytial virus A or B, and human metapneumovirus, using nanofluidic qPCR (Standard BioTools formerly known as Fluidigm). Fisher's exact test and logistic regression analysis were used for between-group comparisons and risk factors associated with common respiratory microbes, respectively.

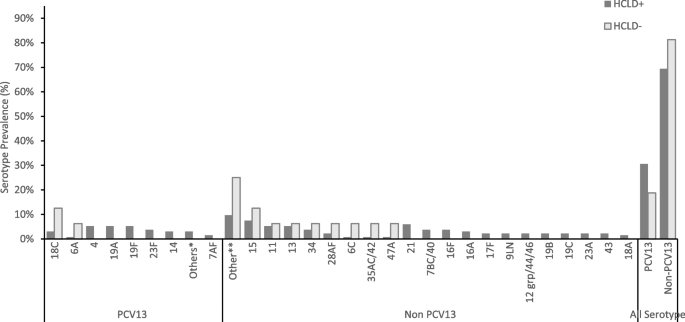

A total of 345 participants (287 HCLD + , 58 HCLD-; median age, 15.5 years [IQR = 12.8–18], females, 52%) were included in the final analysis. The prevalence of SP (40%[116/287] vs. 21%[12/58], p = 0.005) and HRV (7%[21/287] vs. 0%[0/58], p = 0.032) were higher in HCLD + participants compared to HCLD- participants. Of the participants positive for SP (116 HCLD + & 12 HCLD-), 66% [85/128] had non-PCV-13 serotypes detected. Overall, PCV-13 serotypes (4, 19A, 19F: 16% [7/43] each) and NVT 13 and 21 (9% [8/85] each) predominated. The densities of HI (2 × 10 4 genomic equivalents [GE/ml] vs. 3 × 10 2 GE/ml, p = 0.006) and MC (1 × 10 4 GE/ml vs. 1 × 10 3 GE/ml , p = 0.031) were higher in HCLD + compared to HCLD-. Bacterial codetection (≥ any 2 bacteria) was higher in the HCLD + group (36% [114/287] vs. (19% [11/58]), ( p = 0.014), with SP and HI codetection (HCLD + : 30% [86/287] vs. HCLD-: 12% [7/58], p = 0.005) predominating. Viruses (predominantly HRV) were detected only in HCLD + participants. Lastly, participants with a history of previous tuberculosis treatment were more likely to carry SP (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.9 [1.1 -3.2], p = 0.021) or HI (aOR: 2.0 [1.2 – 3.3], p = 0.011), while those who used ART for ≥ 2 years were less likely to carry HI (aOR: 0.3 [0.1 – 0.8], p = 0.005) and MC (aOR: 0.4 [0.1 – 0.9], p = 0.039).

Children with HCLD + were more likely to be colonized by SP and HRV and had higher HI and MC bacterial loads in their nasopharynx. The role of SP, HI, and HRV in the pathogenesis of CLD, including how they influence the risk of acute exacerbations, should be studied further.

Trial registration

The BREATHE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02426112 , registered date: 24 April 2015).

Peer Review reports

In 2019, over 2.8 million children and adolescents were living with HIV globally, 90% in sub-Saharan Africa [ 1 ]. Respiratory infections remain the most common manifestation of HIV among these children and adolescents [ 2 , 3 ]. The scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has increased survival so that growing numbers of children are entering adulthood. In addition, ART has resulted in a reduction in the rate of respiratory disorders, including tuberculosis and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. However, studies in sub-Saharan Africa revealed that approximately 30% of HIV-infected older children experience chronic respiratory symptoms, including chronic cough and reduced tolerance to exercise, which often leads to presumptive tuberculosis treatment [ 8 ]. The clinical and radiological picture of this chronic lung disease is consistent with small airway disease, predominantly constrictive obliterative bronchiolitis [ 9 ].

The pathogenesis of this condition is incompletely understood. It is speculated that HIV-induced chronic inflammation and dysregulated immune activation may play a role [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. A previous study of older children with HIV-associated chronic lung disease (HCLD) conducted by our group demonstrated that there was increased inflammatory activation in children with HCLD (HCLD +) compared to their HIV-infected counterparts without HCLD (HCLD-) [ 13 ]. In the same cohort, there was an association between the carriage of specific bacteria in the nasopharynx and HCLD [ 14 ]. Specifically, we observed that older children with HCLD were more likely to be colonized with Streptococcus pneumoniae (SP) and Moraxella catarrhalis (MC) than their HCLD- counterparts [ 14 ]. The study utilized bacterial culture, which is limited by viability and a narrow spectrum of culturable bacterial species. Although we observed that SP was associated with HCLD, we did not investigate the specific serotypes that may be involved in this condition, which is important to inform pneumococcal immunization. Furthermore, the prevalence of respiratory viruses was also not studied.

Viruses facilitate bacterial infections in the host through various mechanisms, including damaging the respiratory epithelium, modifying the immune response, and altering cell membranes [ 15 ]. Coinfection of viruses and bacteria leads to increased bacterial load, thus making individuals more susceptible to complications related to upper respiratory tract infections [ 16 ]. Prior to COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus and human rhinovirus (HRV) were the most common causative agents of upper respiratory infection and have been linked to exacerbations of COPD [ 17 , 18 ], asthma development [ 17 ], and severe bronchiolitis in children [ 19 , 20 , 21 ].

To overcome these limitations, we investigated the prevalence of respiratory pathogens in both HCLD + and HCLD- participants using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to detect and quantify a large number of bacterial and viral targets and elucidate common SP serotypes (94 serotypes). We also assessed clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with microbial carriage and density.

Materials and methods

Study design, population, and setting.

This case–control study was nested within the BREATHE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02426112, registered date: 24 April 2015) investigating whether azithromycin therapy could improve lung function and reduce the risk of exacerbations among children with HCLD [ 22 ]. BREATHE was a two-site, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, individually randomized trial conducted in Harare (Zimbabwe) and Blantyre (Malawi). The study setting, population, and trial procedures are described elsewhere [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Briefly, we enrolled perinatally HIV-infected participants aged 6 – 19 years with HCLD. HCLD was defined as a forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) z score < -1, with no reversibility (< 12% improvement in FEV1 after salbutamol 200 µg inhaled using a spacer) [ 22 ]. A group of perinatally HIV-infected children without HCLD (FEV1 z score > 0) was also recruited at the same time as the enrollment of trial participants using frequency matching for site, sex, age, and duration of ART to serve as a comparison group for pathogenesis studies. Both groups were on ART for at least six months. All participants were most likely not vaccinated due to the introduction of PCV13 in 2012 in Zimbabwe [ 25 ] and in Malawi in 2011 [ 26 ], making them ineligible for vaccination at that time because of their older age. Swabs were collected between June 1, 2016 and September 31, 2019. Sociodemographic data and clinical history were recorded through an interviewer-administered questionnaire.

Nasopharyngeal swab collection

Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected at baseline from all participants using sterile flocked flexible nylon swabs (Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy). Swabs were immediately immersed in 1 mL PrimeStore® Molecular Transport Medium (MTM) (Longhorn Vaccines & Diagnostics LLC, Bethesda, USA), transported on ice and stored at -80 °C at the diagnostic laboratory at each site. PrimeStore® MTM was used because it is a medium optimized for transporting and storing samples for molecular analyses; it also inactivates potential pathogens and stabilizes nucleic acids [ 27 ]. The samples were batched and transported on dry ice to Cape Town, South Africa, where they were stored at -80 °C until further processing.

Total nucleic acid extraction

Total nucleic acid (TNA) extraction for microbial identification was conducted on NP swabs stored in Primestore® MTM. Briefly, the samples were thawed and vortexed for 10 s, and 400 µl aliquots were transferred into ZR BashingBead™ Lysis Tubes containing 0.5 mm beads (catalog no. ZR S6002–50, Zymo Research Corp., Irvine, CA, United States) for the mechanical lysis steps. Lysis was conducted on a Qiagen Tissue lyser LTTM (Qiagen, FRITSCH GmbH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany) for 5 min at 50 Hz, followed by centrifugation (Eppendorf F-45–30-11, Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 1 min at 10,000 rpm (10,640 g). The supernatants (250 µl) were extracted using the QIAsymphony® DSP Virus/Pathogen Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) on the QIAsymphony SP/AS instrument (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The total nucleic acid was eluted in 70 µl DNA elution buffer into the Elution Microtube (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and immediately stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

Real-time qPCR using the biomark HD system (Fluidigm assay)

Nanofluidic qPCR testing was performed at the WITS-VIDA Research Unit, Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg, South Africa as previously described [ 28 , 29 ]. Briefly, all extracts were tested for 94 SP serotypes together with 12 bacterial species (SP, HI, MC, Staphylococcus aureus [SA], Neisseria lactamica , Neisseria meningitidis , Streptococcus pyogenes , Bordetella pertussis , Bordetella holmesii , Klebsiella pneumoniae , Acinetobacter baumanii and Streptococcus oralis ), 6 HI serotypes and 8 viruses (respiratory syncytial virus A and B, human rhinovirus, influenza A and B, human parainfluenza 1 and 3, and human metapneumovirus). Furthermore, all samples were previously cultured for SP, HI, MC and SA as described elsewhere [ 14 ]. These microbial targets (Table S1) included on the nanofluidic panel might be associated with HCLD and are the most frequent pathobionts in the nasopharynx. A detailed list of these microbial targets can be found in the supplementary material (Table S1). For SP, positive samples were defined as those with a Cycle of quantification (Cq) value ≤ 36 for each serotype-specific qPCR target and positive for both Lyt A and Pia B. Negative samples were defined as those with Cq values ≥ 36 for each target.

The bacterial or serotype densities were determined following the method outlined by Downs et al . [ 28 ]. Briefly, culture controls and synthetic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) template gene fragments (gBlocks) were included in the assay as external calibrators, reported as copy numbers or gene equivalents, respectively. A DNA library was prepared for the targeted pneumococcal serotypes or other bacterial species at an average concentration ranging from 10 3 to 10 4 CFU/ml. For assay-sets meeting the defined efficiency criteria (90–110%), the relative quantification of bacterial density was determined by extrapolating using the linear equation derived from standard curves of the calibrators (control strains and gBlocks with known densities), employing the equation and reported as log 10 genomic equivalents/ml:

Data management and statistical analysis