The Newsroom (American TV series)

The Newsroom (2012–2014) is an American drama television series created by Aaron Sorkin , airing on HBO , that chronicles the behind-the-scenes events at the fictional Atlantis Cable News (ACN) channel.

- 1.1 We Just Decided To [1.01]

- 1.2 News Night 2.0 [1.02]

- 1.3 The 112th Congress [1.03]

- 1.4 I'll Try To Fix You [1.04]

- 1.5 Amen [1.05]

- 1.6 Bullies [1.06]

- 1.7 5/1 [1.07]

- 1.8 The Blackout Part 1: Tragedy Porn [1.08]

- 1.9 The Blackout Part II: Mock Debate [1.09]

- 1.10 The Greater Fool [1.10]

- 2.1 First Thing We Do, Let's Kill All the Lawyers [2.01]

- 2.2 The Genoa Tip [2.02]

- 2.3 Willie Pete [2.03]

- 2.4 Unintended Consequences [2.04]

- 2.5 News Night with Will McAvoy [2.05]

- 2.6 One Step Too Many [2.06]

- 2.7 Red Team III [2.07]

- 2.8 Election Night, Part I [2.08]

- 2.9 Election Night, Part II [2.09]

- 3.1 Boston [3.01]

- 3.2 Run [3.02]

- 3.3 Main Justice [3.03]

- 3.4 Contempt [3.04]

- 3.5 Oh Shenandoah [3.05]

- 3.6 What Kind of Day Has It Been [3.06]

- 5 External links

We Just Decided To [1.01]

News night 2.0 [1.02], the 112th congress [1.03], i'll try to fix you [1.04], amen [1.05], bullies [1.06].

[Sloan has just finished a broadcast, during which she overruled a Japanese translator and questioned him herself, and then committed a serious breach of ethics, causing Don to become quite agitated in the control room causing her to take her earpiece out during broadcast. She comes out of the studio to find Don lounging in a chair in the bullpen]

The Blackout Part 1: Tragedy Porn [1.08]

The blackout part ii: mock debate [1.09], the greater fool [1.10], first thing we do, let's kill all the lawyers [2.01], the genoa tip [2.02], willie pete [2.03], unintended consequences [2.04], news night with will mcavoy [2.05], one step too many [2.06], red team iii [2.07].

[Cuts back to the newsroom then back to Will]

Election Night, Part I [2.08]

Election night, part ii [2.09], boston [3.01], main justice [3.03], contempt [3.04], oh shenandoah [3.05], what kind of day has it been [3.06].

- Jeff Daniels - Will McAvoy

- Emily Mortimer - MacKenzie "Mac" McHale

- John Gallagher - James "Jim" Harper

- Alison Pill - Margaret "Maggie" Jordan

- Thomas Sadoski - Don Keefer

- Dev Patel - Neal Sampat

- Olivia Munn - Sloan Sabbith

- Sam Waterston - Charlie Skinner

- Jane Fonda - Leona Lansing

- Chris Messina - Reese Lansing

External links

- The Newsroom quotes at the Internet Movie Database

- The Newsroom at TV.com

- Official website

- Cancelled shows

- Political drama TV shows

- 2010s American drama TV shows

Navigation menu

Law Journal for Social Justice

“The First Step in Solving Any Problem is Recognizing There is One” … or, is it?

“The First Step in Solving Any Problem is Recognizing There is One [1] ” … or, is it?

Analyzing the judicial punting regarding fossil fuels and Juliana v United States

By: Annabelle Abel

Introduction

On January 17, 2020, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit released an opinion illuminating the current social and judicial attitude towards the issue of climate change: admitting to the problem but denying the authority to create or enforce a solution. [2]

Juliana v United States , a case out of Portland, Oregon, draws attention to the multifaceted issue of climate change by utilizing the perspectives of twenty-one young plaintiffs, all under the age of twenty-two years old. The plaintiffs argued that the US, the President, and federal officials collectively permitted the use and extraction of fossil fuels, causing environmental harm. [3] The plaintiffs codified the environmental harms into various constitutional claims, thus alleging that climate change violated substantive due process, equal protection, the Ninth Amendment, and the Public Trust Doctrine. [4]

Judicial Punting

Juliana’s procedural posture prior to the January 17th opinion speaks to the ability of courts to recognize a problem, but also highlights the courts’ inability to fashion a solution that solves the problem without violating the constitution or overstepping the separation of powers. While the district court found that the plaintiffs presented a viable “danger-creation due process claim,” amongst other things,the district court ordered a stay pending a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision, effectively taking no real action. [5] Further, the Supreme Court of the United States denied the government’s motion for a stay of proceedings, although noting that “the breadth of respondents’ claim is striking.” [6] Finally, in the appeal to the Ninth Circuit, Circuit Judge Hurwitz held that although the plaintiffs’ claims had some undeniable merit, they “failed to demonstrate that the injunctive relief they sought was within the power of an Article III court, as required for redressability element for Article III standing.” [7]

As a result, the plaintiffs and the public are left without any judicial solution aside from the suggestion to make the same case and arguments to “political branches or to the electorate at large, the latter of which can change the composition of the political branches through the ballot box.” [8] But, with global atmospheric carbon levels skyrocketing to a level not seen in three million years, and with sea levels expected to rise approximately 23 feet by 2100, time is certainly of the essence and voting is no easy feat, especially in the politically charged era created after the 2018 election of President Trump. [9] Of further concern are the steps taken by the Trump Administration to overturn environmental politics enacted by the Obama Administration. [10]

The Solution

First and foremost, we can vote, we can organize political rallies, and we can take steps in our daily lives to mitigate our own carbon footprints. But with the climate crisis at a truly astronomical global level, grassroots efforts to change the problem feel like merely a drop in the bucket.

However, all hope for a judicial remedy is not lost. As an environmental law professor at Yale Law School hypothesizes, Juliana v United States may have opened the door for further litigation of other, related cases because while no action has been taken on this case, there is widespread judicial recognition of the problem. [11] Further, of the three judges on the Ninth Circuit panel hearing Juliana , one judge wrote a strongly worded dissent, arguing the urgency at hand and the need for judicial intervention. [12]

More optimistically is the fact that in US history, only 1100 climate change cases have ever been brought within the US, and of this number, 50 of these cases are currently pending. [13] While the Juliana panel was split, anything is possible, especially in a more liberal circuit, and the number of climate change cases on the docket suggests a different outcome may come sooner than expected. [14]

Until then, vote, take action, and fight the good fight that the judiciary continues to punt elsewhere. Time is ticking, and our last chance to act is now.

[1] Aaron Sorkin, The Newsroom (HBO 2012).

[2] Juliana v United States, No. 18-36082 (9th Cir. Jan. 17, 2020) (remanding with instructions).

[4] Id. (referencing that the public trust doctrine implicates the government’s responsibility to protect certain natural resources for public use and enjoyment).

[5] Juliana v United States, No. 6:15-cv-01517-AA (D. Or. Nov. 21, 2018).

[6] Juliana, supra note 2.

[10] John Schwartz, Young People are Suing the Trump Administration Over Climate Change. She’s Their Lawyer , The New York Times (Oct. 23, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/23/climate/kids-climate-lawsuit-lawyer.html .

[11] Madeleine Carlisle, A Federal Court Threw Out a High Profile Climate Lawsuit. Here’s What is Might Mean for the Future of Climate Litigation, Time (Jan. 19, 2020, 1:43 PM), https://time.com/5767438/climate-lawsuit-kids/ .

Share this:

Published by Law Journal for Social Justice at Arizona State University

The Law Journal for Social Justice ("LJSJ") is the first student-run and student-created online journal at Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law. LJSJ aims to edit, publish, and produce notable works through its online website from legal scholars, practitioners and law students. LJSJ also publishes twice a year, featuring articles that focus on important, novel and controversial areas of law. LJSJ will provide a fresh perspective and propose solutions to cornerstone issues that are often not discussed, which may also have the potential to positively impact local communities. View all posts by Law Journal for Social Justice at Arizona State University

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Protect your data

This site uses cookies and related technologies for site operation, and analytics as described in our Privacy Policy . You may choose to consent to our use of these technologies, reject non-essential technologies, or further manage your preferences.

- Career Advice

- Five Steps To Create a...

Five Steps To Create a Problem-Solving Process (Plus Tips!)

8 min read · Updated on August 31, 2023

Conquering workplace challenges fuses strategy and art

Sometimes, it can seem that obstacles are as prevalent as opportunities. When you're good at solving problems, though, you have the power to navigate issues with relative ease. In fact, problem solving is more than a skill - it's a tool that you can use to fuel career growth and success.

As an effective problem solver, you use innovative thinking, demonstrate leadership, and build resilience and confidence. Often, the people you work with come to trust that you're the person to go to when there's a challenge. This could be just the stepping stone you need to move into a leadership role .

Of course, problems range in complexity depending on your industry. But by having a five-step problem-solving process in place, you can enhance both efficiency and effectiveness. In this article, we'll explore tips to help you master the skill, strategy, and art of problem solving.

Identify, analyze, resolve, execute, evaluate

What's the definition of problem solving? It's quite simple. You have to come up with solutions to challenges or issues.

The first step to fixing any problem is recognizing that there is one. Then the trick is to engage with each step of the problem-solving process to incorporate analytical thinking , adaptability, and collaboration skills to build a framework for addressing challenges and driving positive outcomes.

Step 1: Identify

Identifying the problem may be simple, or it could be a detailed cognitive process that breaks the issue into manageable components. Either way, what you do during the identify step of the problem-solving process sets the stage for the next steps in problem solving.

Step 2: Analyze

Consider underlying factors and devise strategies. Here's where the art part of your problem-solving strategy becomes important. As you gather details about the problem, employ critical thinking to uncover the root causes and potential implications.

Step 3: Resolve

Once you have a thorough understanding of the issue, it's time to get creative. Develop some reasonable solutions that are aligned with the capabilities of your team and the mission, vision, and values of your company. Your problem-solving method could involve any one of the following - or even a combination of several:

Encourage your team to learn new technologies

Reallocate some resources

Restructure organizational elements

Draft new operating procedures

Implement brainstorming sessions

Develop metrics

Step 4: Execute

After you've outlined the solutions and decided which ones you think will resolve the problem, it's time to put them into place. The execution phase is the bridge between theory and practice.

Translate the solutions into actionable steps that produce tangible results

Clearly communicate the actionable steps to the relevant stakeholders - your team, colleagues, or managers

Delegate tasks based on team member acumen

Empower those you delegate tasks to by fostering a sense of ownership

Track the progress of your solutions

Overcome challenges, including unforeseen obstacles and stakeholder resistance

Step 5: Evaluate

Just because you think you solved the problem doesn't mean you actually did. It's critical to double-check your work and make sure there are no hiccups. Here's a list of 10 evaluative questions you can work through, to ensure that your problem-solving solutions were impactful:

Did the solutions effectively address the root cause of the problem?

Do you see the desired results?

What impact can you see on your team or the company?

Has there been a noticeable enhancement in efficiency, productivity, or overall performance?

Have any unintended consequences or new challenges arisen as a result of the implemented solution?

Can the solution be sustained in the long term, or is it a short-term fix?

Have stakeholders, such as team members or customers, reported positive experiences or feedback?

Have the predefined performance metrics and goals been achieved or exceeded?

Are there any new aspects of the problem that emerged after implementing the solution?

Which aspects of the solution would you retain and which would you modify?

When you reflect on the outcome of your problem solving strategies, you not only validate the effectiveness of your approach but you can also find insights for continuous improvement and refinement for future endeavors.

Problem solving isn't just for leaders

Sometimes, it seems that only managers and senior executives can engage in effective workplace problem solving. That's simply not the case. It doesn't matter if you're a fresher who's just graduated college or someone with decades of experience, you can employ problem-solving techniques and become a master problem solver.

You've likely heard of hard skills and soft skills ; you may have even seen problem solving lumped in with other soft skills. There are three essential soft skills you'll need to be good at to solve workplace problems:

Analytical thinking

Adaptability, collaboration.

Let's start with a foundational problem-solving skill. Analytical thinking is something you'll use in every step of your five-step problem-solving process, from identifying the problem to coming up with and executing solutions and measuring the success of those solutions. Being able to analyze trends, anticipate shifts, and make informed decisions along the problem-solving path, you'll be assured of success.

A real-world example: Sally is a new graduate and has secured her first job. After a few days at work, she wants to start making a name for herself by identifying a dip in sales. She dissects the customer engagement data and finds there has been a shift in consumer preferences. She knows that a new targeted marketing strategy could re-engage customers and bring sales back up.

Toss aside any notions that the plans you set into place to solve a problem are set in stone. They're not! Being able to make course corrections to change outcomes is at the heart of being adaptable . This soft skill becomes more and more important every day because of how quickly things change in business. Technology advances, economic fluctuations come into play, and unforeseen global events can wreak havoc on the best-laid problem-solving solutions. Think about how adaptable people had to be a few years ago when Covid shut the world down – there were tons of never-before-faced problems that ultimately got solved.

A real-world example : John has been employed in the technology sector for a little over 20 years. He's achieved the coveted role of CTO and found himself overseeing a team that had to transition into remote work. Because he's kept up with emerging technologies and the latest trends, he sets up processes that allow his team to enjoy a seamless shift with minimal impact on productivity.

When you have a problem-solving project in front of you, you'll often have to get people involved to help you to execute the solutions you come up with. Effective communication , organizational synergy, and a harmonious fusion of experiences can lend fresh insights to problem solving.

A real-world example: Marcus is involved in a complex project involving supply chain optimization. He works with geographically-dispersed stakeholders of all levels and has become an expert at pooling together specialized knowledge to create holistic solutions.

How do great problem-solving skills affect your career goals?

Challenges in life and at work are inevitable; by aligning your problem-solving skills with your career goals, not only will you be able to overcome immediate challenges, but you'll also cultivate a powerful tool for your job search toolkit. When you're good at solving problems and can show that you're good at it through accomplishment statements on your resume, your career trajectory will likely be positively impacted. In fact, there are several success stories that prove the journey to excellence is marked by innovative problem solving. Here are just a few:

Elon Musk: Musk's SpaceX faced immense challenges in developing reusable rockets. His innovative, problem-solving approach led to breakthrough solutions, revolutionizing space travel.

Indra Nooyi: As the former CEO of PepsiCo, Nooyi tackled the declining demand for sugary beverages by diversifying the product portfolio and focusing on healthier options, showcasing adaptability and strategic problem solving.

Nelson Mandela: Mandela's ability to collaborate across racial divides and negotiate solutions was instrumental in ending apartheid in South Africa.

Grace Hopper: A computer science pioneer, Hopper's analytical thinking led to the development of the first compiler, revolutionizing programming.

An invaluable asset

As you progress in your career, your skill in resolving a problem will set you apart from the rest of the job-seeking crowd as an invaluable asset. Whether you're identifying opportunities for growth, addressing operational inefficiencies, or strategizing through crises, the ability to solve problems creatively and effectively can become one of the key drivers for the advancement of your career. Essentially, strong problem-solving skills empower you to overcome challenges, seize opportunities, and carve a path of consistent achievement in your professional journey.

TopResume can help you to showcase exceptional problem-solving skills on your resume. Why not submit yours for a free resume review today, to make sure that you're giving this skill the prominence it deserves?

Recommended reading:

How to List Problem Solving Skills on a Resume

Divergent Thinking: Should You Include This Skill on Your Resume?

Higher Order Thinking Explained

Related Articles:

Don't “Snowplow” Your Kids' Job Search — Set Them Up for Success Instead

What Kind of Job Candidate Are You?

Why December is the Best Time of Year to Look for a Job

See how your resume stacks up.

Career Advice Newsletter

Our experts gather the best career & resume tips weekly. Delivered weekly, always free.

Thanks! Career advice is on its way.

Share this article:

Let's stay in touch.

Subscribe today to get job tips and career advice that will come in handy.

Your information is secure. Please read our privacy policy for more information.

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

The Newsroom 2012

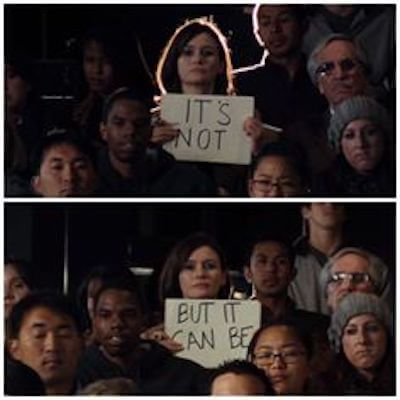

Will McAvoy: It's not the greatest country in the world, professor, that's my answer.

Moderator: You're saying...

Will McAvoy: Yes.

Moderator: Let's talk about...

Will McAvoy: Fine. Sharon, the NEA is a loser. Yeah, it accounts for a penny out of our paychecks, but he gets to hit you with it anytime he wants. It doesn't cost money, it costs votes. It costs airtime and column inches. You know why people don't like liberals? Because they lose. If liberals are so f***in' smart, how come they lose so GODDAM ALWAYS!

Sharon: Hey...

Will McAvoy: [turns to Lewis] And with a straight face, you're going to tell students that America is so starspangled awesome that we're the only ones in the world who have freedom? Canada has freedom, Japan has freedom, the UK, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Australia, BELGIUM has freedom! Two hundred and seven sovereign states in the world, like 180 of them have freedom.

Moderator: All right...

Will McAvoy: And yeah, you... sorority girl. Just in case you accidentally wander into a voting booth one day, there are some things you should know, and one of them is: There is absolutely no evidence to support the statement that we're the greatest country in the world. We're seventh in literacy, twenty-seventh in math, twenty-second in science, forty-ninth in life expectancy, 178th in infant mortality, third in median household income, number four in labor force, and number four in exports. We lead the world in only three categories: number of incarcerated citizens per capita, number of adults who believe angels are real, and defense spending, where we spend more than the next twenty-six countries combined, twenty-five of whom are allies. None of this is the fault of a 20-year-old college student, but you, nonetheless, are without a doubt a member of the WORST-period-GENERATION-period-EVER-period, so when you ask what makes us the greatest country in the world, I don't know what the f*** you're talking about! Yosemite?

Will McAvoy: [pause] We sure used to be. We stood up for what was right. We fought for moral reasons, we passed laws, struck down laws for moral reasons. We waged wars on poverty, not poor people. We sacrificed, we cared about our neighbors, we put our money where our mouths were, and we never beat our chest. We built great big things, made ungodly technological advances, explored the universe, cured diseases, and we cultivated the world's greatest artists and the world's greatest economy. We reached for the stars, acted like men. We aspired to intelligence; we didn't belittle it; it didn't make us feel inferior. We didn't identify ourselves by who we voted for in the last election, and we didn't scare so easy. We were able to be all these things and do all these things because we were informed. By great men, men who were revered. The first step in solving any problem is recognizing there is one. America is not the greatest country in the world anymore.

Will McAvoy: [to moderator] Enough?

Share your thoughts on this The Newsroom's quote with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Quote of the Day Today's Quote | Archive

Would you like us to send you a free inspiring quote delivered to your inbox daily.

Please enter your email address:

Use the citation below to add this movie quote to your bibliography:

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"The Newsroom Quotes." Quotes.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 9 Jul 2024. < https://www.quotes.net/mquote/912169 >.

Know another quote from The Newsroom?

Don't let people miss on a great quote from the "the newsroom" movie - add it here, the web's largest resource for, famous quotes & sayings, a member of the stands4 network, our favorite collection of, famous movies.

Browse Quotes.net

Are you a quotes master, "adventure is worthwhile in itself".

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2022

The first step is recognizing there is a problem: a methodology for adjusting for variability in disease severity when estimating clinician performance

- Meagan Bechel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0600-3774 1 ,

- Adam R. Pah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9892-0774 2 , 3 ,

- Stephen D. Persell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2462-1314 4 , 5 ,

- Curtis H. Weiss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3102-5273 6 &

- Luís A. Nunes Amaral ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3762-789X 2 , 7 , 8

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 22 , Article number: 69 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2550 Accesses

27 Altmetric

Metrics details

Adoption of innovations in the field of medicine is frequently hindered by a failure to recognize the condition targeted by the innovation. This is particularly true in cases where recognition requires integration of patient information from different sources, or where disease presentation can be heterogeneous and the recognition step may be easier for some patients than for others.

We propose a general data-driven metric for clinician recognition that accounts for the variability in patient disease severity and for institutional standards. As a case study, we evaluate the ventilatory management of 362 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) at a large academic hospital, because clinician recognition of ARDS has been identified as a major barrier to adoption to evidence-based ventilatory management. We calculate our metric for the 48 critical care physicians caring for these patients and examine the relationships between differences in ARDS recognition performance from overall institutional levels and provider characteristics such as demographics, social network position, and self-reported barriers and opinions.

Our metric was found to be robust to patient characteristics previously demonstrated to affect ARDS recognition, such as disease severity and patient height. Training background was the only factor in this study that showed an association with physician recognition. Pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) training was associated with higher recognition (β = 0.63, 95% confidence interval 0.46–0.80, p < 7 × 10 − 5 ). Non-PCCM physicians recognized ARDS cases less frequently and expressed greater satisfaction with the ability to get the information needed for making an ARDS diagnosis ( p < 5 × 10 − 4 ), suggesting that lower performing clinicians may be less aware of institutional barriers.

Conclusions

We present a data-driven metric of clinician disease recognition that accounts for variability in patient disease severity and for institutional standards. Using this metric, we identify two unique physician populations with different intervention needs. One population consistently recognizes ARDS and reports barriers vs one does not and reports fewer barriers.

Peer Review reports

The first step to solving a problem is recognizing that one exists; this principle is widely accepted and contributes to the foundation of both implementation science and quality improvement. In clinical medicine, this principle is applied on multiple levels of care delivery. At the organizational level, healthcare institutions monitor quality of care indicators such as nosocomial infection incidence, readmission rates, and clinician guideline adherence, with the goal of intervening early should an issue develop. Routine data collection and analysis is far more cost-effective than routine interventions on all individuals or units within an institution. In this work, we extend this same logic to the individual clinician level, where recognition of a problem is frequently synonymous with recognition of disease.

At the individual provider level, recognition of disease is the first step in all clinical decision making. No medical treatment is fully benign and therefore, treatment is not indicated without a diagnosis or high suspicion of a specific diagnosis. As a result, recognition of disease becomes a prerequisite to any decision regarding the adoption of a clinical innovation. If a clinician decides that a disease state does not exist in a patient, there is no need for that clinician to consider potential treatment choices for that supposedly non-existent disease state. Thus, disease recognition challenge needs to be addressed before any other barrier to adoption.

However, the relative difficulty of the disease recognition task can vary between patients, making measuring clinician disease recognition challenging. The same condition can present with different clinical signs and/or on a spectrum of severity, with some diagnoses being easier than others. Thus, while simple performance measures of clinician disease recognition – such as proportion of correct diagnoses – are useful for patient outcome assessment, it does not capture the complexity of patient care and has limited utility for comparing individual clinicians at the same institution, the same clinician over time, or untangling an individual clinician’s performance from that of the overall institution. It is the same logic that drives using risk-adjustment when calculating readmission rates; there are many factors that go into whether a patient will be readmitted, only some of which a physician can reasonably intervene on. Readmissions cannot be fully eliminated by the hospital staff, but they can be minimized by certain staff actions and institutional resources and policies.

In this work, we extend this principle to clinician disease recognition and present a data-driven methodology that accounts for variability in patient disease severity. The goal of this recognition measure is not to serve as a patient care quality measure, but instead be a standardized measure for evaluating a physician’s progress towards a patient care goal within the context of the overall performance of the institution. Using this metric, we then examine the relationship between recognition and physician characteristics - such as demographics, social network position, and self-reported barriers – using the case study of ventilator management in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Low tidal volume ventilation (LTVV) for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Historically, the adoption of innovation in clinical medicine has been slow [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] and the use of LTVV for patients with ARDS is a prime example. ARDS is a syndrome of acute inflammatory lung injury leading to hypoxemic respiratory failure. It is frequently associated with a known risk factor, such as pneumonia or inhalation injury [ 5 ], and thus often found in critically-ill and medically complex patients. Prior to the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, ARDS affected 10.4% of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions worldwide [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The current prevalence is likely higher given that SARS-CoV-2 infection has been shown to be a risk factor for ARDS [ 8 ]. Pre-pandemic mortality estimates for ARDS ranged from 27 to 45% [ 6 ], with additional reports of significant post-recovery morbidity [ 9 , 10 ].

LTVV is a ventilator management strategy focused on lowering mechanically-delivered volumes and pressures with the goal of preventing ventilator-associated lung injury. It was first trialed in patients with ARDS in the 1998 and multiple subsequent trials have shown that it reduces mortality [ 11 , 12 ]. LTVV has since become a strongly-recommended practice for patients with ARDS, incorporated into the American Thoracic Society guidelines [ 12 ].

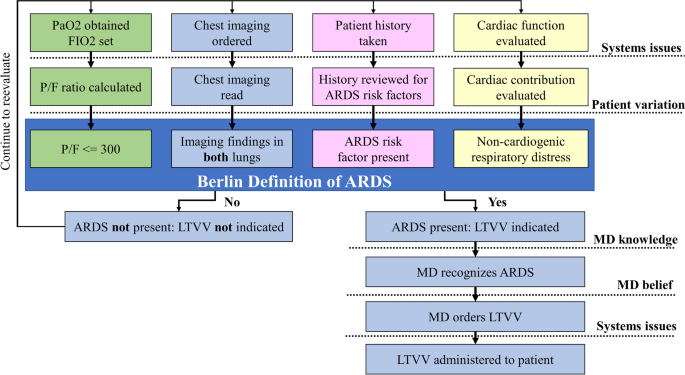

Yet, clinical LTVV utilization remains as low as 19% of ARDS patients [ 7 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Research has demonstrated that while physician ‘buy-in’ for LTVV is high, ARDS under-recognition remains a major barrier to LTVV use [ 7 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Furthermore, there is significant evidence that patient characteristics, such as ARDS severity, strongly influence physician recognition of ARDS [ 7 , 15 , 17 , 19 , 21 , 27 ]. ARDS is diagnosed using the Berlin Definition [ 5 ], which is a set of clinical criteria that a patient must meet. The Berlin Definition (Fig. 1 ) requires the synthesis of multiple sources of information, including lab values, ventilator settings, imaging, and patient history. ARDS is an ideal case study for our recognition metric due to the clear need for an increase in recognition, the complexity of its diagnosis, and the variability of its presentation.

Implementation of LTVV for ARDS. The implementation of LTVV is a multi-step process that starts with ARDS development and recognition. ARDS recognition requires the synthesis of multiple types of clinical information. The standardized tidal volume delivered to a patient, whether it falls within the LTVV range or not, is the end product of clinician decision making. Several potential barriers (dotted lines) may delay or prevent the implementation of LTVV.

Data acquisition

Patient data.

We have previously described the development and assessment of the ARDS cohort in this study, which included 362 patients who met the Berlin Definition of ARDS at four hospitals in the Chicago region in 2013 [ 20 ]. Patient data was obtained from the electronic health records serving the participating hospitals. For this study, we use height and sex to calculate predicted body weight (sex neutral surrogate for height) as well as all tidal volumes (mL/kg) and P a O 2 /F I O 2 ratios (mmHg) available during the patient’s disease course. These data were collected as part of an observational study focused on understanding ARDS recognition and management, and implementation of LTVV. The methods and insights gleaned from this work will be incorporated into a larger multicenter study of ARDS recognition and management, and barriers to implementation of LTVV (NIH R01 HL140362).

Physician data

We have previously described the survey used in this study, which included the critical care physicians who were identified as caring for the patients in the ARDS cohort described above [ 26 ]. The survey included questions on physician attitudes towards LTVV and innovation in general, perceived barriers and facilitators to LTVV use, and professional and social connections with other ICU physicians. Physicians who met cohort inclusion criteria but were missing data points were only excluded from the analyses that requires those missing data points. Data availability is reported in Additional File, Supp Table 1 .

Calculation of ARDS recognition

Our ARDS recognition metric that compares an individual physician’s observed ARDS recognition to that physician’s expected ARDS recognition given their specific patient census. The calculation of each physician’s recognition metric includes only the data generated during that physician’s specific pairing with his/her patients. Due to different data collection procedures at different clinical sites, we were only able to calculate the ARDS recognition metric for the largest site in our previous study [ 20 ].

Observed recognition

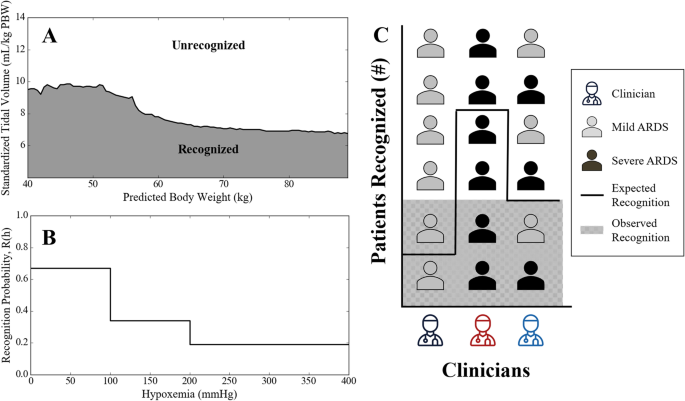

For each patient in a physician’s census, we assign a label of “recognized” or “not recognized.” This label is inferred from the standardized tidal volume selected by the clinician to be delivered to the patient. This inference is based on our previously developed model of physician recognition of ARDS. Previously, we quantified the impact of patient characteristics on physician recognition of ARDS and subsequent LTVV delivery, by comparing physician behavior with ARDS patients to physician behavior with a novel hypoxemic ‘control’ cohort [ 27 ]. We found that the largest confounding characteristics in both ARDS and control cohorts was patient height (reported as the sex-neutral ‘predicted body weight’). We developed a model that accounts for this by dividing the predicted body weight (PBW) vs standardized tidal volume (mL/kg PBW) space into “recognized” and “not recognized” regions (Fig. 2 A). Patients in the “recognized” region experience physician behavior more similar to that exhibited with ARDS patients as compared to physician behavior seen with the control patients. In this work, we map each physician’s patient census to this space and infer their observed individual recognition, N obs , as the number of their patients falling within the “recognized” region.

Components of the ARDS recognition metric. A) Observed Recognition: we designate an ARDS patient as recognized if their standardized tidal volume falls below the recognition line for their predicted body weight. B) Expected Recognition: we use a stepwise function relating hypoxemia and recognition probability in eq. 1 to calculate an expected baseline recognition rate for each physician. C) Recognition Metric: we compare the observed and expected recognition for each physician to account for patient presentation variability.

Expected recognition

From a patient outcomes perspective, a physician’s expected recognition would be 100% of the ARDS patients they see. However, the goal of our recognition metric is to measure a physician’s progress relative to another physician, their progress over time, and/or to an institution’s past average; it is not intended to replace overall missed diagnosis rates. Thus, we use the current group average of all physicians within the same institution as a physician’s expected recognition performance. The idea is that by identifying both high and low performers, the institution will be better able to learn which physicians should be targeted in order to improve overall institutional performance.

In order to accomplish this, we must account for the severity of ARDS (measured by the hypoxemia categories set forth in the Berlin definition) because we and others have previously demonstrated that the severity of ARDS has an impact on a physician’s ability to recognize ARDS, with sicker patients being easier to recognize [ 7 , 22 ]. To establish a baseline expected recognition rate for each physician that accounts for this influence, we used the following equation:

N exp : expected number of patients to be recognized.

h i : hypoxemia severity category (mild, moderate, or severe) [ 5 ] of patient i.

R(h i ): institutional level recognition rates of mild, moderate, or severe patients [ 27 ] (Fig. 2 B).

N j : number of patients cared for by physician j.

The recognition rates, R(h i ), in Eq. 1 are for the whole ARDS cohort by hypoxemia severity, which we estimated in prior work via mixture model as 22% for mild hypoxemia (P a O 2 /F I O 2 in range 200-300 mmHg), 34% for moderate hypoxemia (P a O 2 /F I O 2 in range 100-200 mmHg), and 67% for severe (P a O 2 /F I O 2 < 100 mmHg) [ 27 ]. Expected recognition is rounded down to the nearest whole patient to account for the binary nature of ARDS diagnosis.

ARDS recognition metric

Our ARDS recognition metric R (Fig. 2 C) compares the cumulative probabilities of the observed and expected recognition scenarios

To calculate R , consider a physician with a patient census {h 1 , …, h Nj }, and that for each patient i in the census there is an institutional level recognition rate, R (h i ), appropriate for the patient’s hypoxemia severity (Fig. 2 B). The expected number of recognized patients for that physician’s census is.

where the three subscripts refer to mild, intermediate, and severe hypoxemia, and f is the fraction of patients in the census with a given hypoxemia severity. Since the number of patients in a physician’s census may not be large and because N exp is not necessarily an integer, calculating P (≤ N obs ) or P (≤ N exp ) is more easily done by simulation then by enumeration. Thus, we generated 1000 sequences of recognized/not-recognized outcomes for the physician’s patient census according to the recognition probability of each patient’s hypoxemia severity (see Additional File, Supplemental Methods , Probability Density Function Distribution Generation). This process enabled us to estimate the probability of each number between 0 and N j of recognized patients for each physician. By using the cumulative probability (Eq. 2 ), we ensure that physicians recognizing more patients than expected are assigned positive performance values, while physicians recognizing less patients are assigned negative values. Physicians performing at the expected level for their peer group are rated at 0.

ARDS recognition metric covariates

Metric robustness evaluation.

We used univariable ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to assess the robustness of our recognition metric. We evaluated whether our metric showed any correlation with key variables including predicted body weight, hypoxemia (lowest P a O 2 /F I O 2 ), total number of patients treated, and mortality proportion within each physician’s census. For predicted body weight, we used summary statistics of the physician’s patient census (mean, median, proportions in the central, single standard deviation, and second standard deviation ranges) and for hypoxemia, we used the proportion of the patient population with severe hypoxemia (P a O 2 /F I O 2 100).

Physician characteristics

We sought to evaluate the relative associations between physician recognition of ARDS and physician characteristics that have been previously shown to have an impact on clinical decision-making and use of evidence-based practices: physician demographics [ 28 ], social network position [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ], and attitude survey responses. For demographic variables and social network attributes, we used a feedforward OLS regression approach with our recognition metric as the dependent variable and physician characteristics as independent variables. Demographic univariable analysis was performed first, as demographic characteristics have been previously shown to affect network connections [ 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Demographic variables included: training background (specialty), age, sex, and year of training completion (ordinal and before/after ARDSNet LTVV trial [ 11 ]).

Next, we constructed four different social networks (patient contact [ 43 ], advice seeking, friendship, and innovation) and calculated 8 positional metrics for each physician (betweenness, closeness, degree, Katz centrality, k-shell embeddedness, participation, role, and community membership). For detailed descriptions of network construction and each positional metric, see Additional File, Supplemental Methods , Network Construction, and Additional File, Supp Table 2 . All centrality characteristics (betweenness, closeness, degree, and Katz) were calculated using the Networkx Python package (v 1.11), except embeddedness which was calculated using custom code [ 44 ]. Participation, role, and community membership were calculated using netcarto (v1.15). All positional metrics were normalized for the number of physicians in the network, except community membership, which was treated as a categorical variable. Significant demographic variables were included as a fixed effect in multivariable OLS regressions with positional metrics as an additional independent variable. Each positional metric was evaluated in a separate regression.

For the survey response analysis, we used both an individual question and a collective group approach. Survey questions (non-demographic, non-network) were first filtered for those that showed a maximum range of responses. To examine associations between individual physician survey responses and physician recognition, we used a Kruskal-Wallis H-test to evaluate differences in recognition between categories of survey answer for each question (Python Scipy package v0.18.1). To evaluate for differences in survey response between groups of physicians, we split physicians by the significant demographic or positional metric identified in the prior feedforward regression analysis. We then used a Mann-Whitney U test to assess differences in the responses from these groups to the same filtered question pool (Python Scipy package v0.18.1).

Sensitivity analyses

All analyses were repeated using two alternative ARDS recognition measures that have been previously used in literature: 1) the proportion of worked shifts during which the physician delivered LTVV and 2) the proportion of patients that a physician cared for who received LTVV at any point during their disease course. For these alternative measures, we used a strict interpretation of LTVV use (defined as ≤6.5 mL/kg PBW) as put forth by the original ARDSNet LTVV trial [ 11 ]. These measures do not adjust for the impact of patient height on standardized tidal volume (mL/kg PBW) or the influence of ARDS severity on clinician recognition of ARDS. All regression results using these alternative recognition metrics as the dependent variable were consistent with the regression results when our recognition metric was used.

Statistical significance

We used α = 0.01 instead of 0.05 to ensure the statistical strength of our findings [ 45 ] and applied the Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses. There were 140 comparisons where our recognition metric was the dependent variable, thus we set 7 × 10 − 5 (0.01/140) as the threshold for statistical significance for these analyses. For the survey analysis, there were 20 questions evaluated, resulting in a threshold of 5 × 10 − 4 (0.01/20).

Collected data

This study includes 92 physicians, 74 (80%) of which responded to the survey. Forty-eight physicians (52%) cared for patients in the ARDS cohort during our data collection period and had their ARDS recognition estimated. Of those physicians who responded to the survey and had their ARDS recognition estimated, the training distribution is as follows: 23 pulmonary/critical care, 10 anesthesia/critical care, 8 cardiology, 5 surgical/critical care, and 2 neurology/critical care. Twenty-six (54%) of these physicians were male and most frequently reported age range was 35–44 years (21, 43%). We evaluated 567 physician-patient pairings as some patients had multiple physicians during their disease course (Additional File, Supp Table 3 ). Moderate ARDS patients were most common with 247 physician-patient pairings (43.6%) and severe ARDS patients were least common with 117 physician-patient pairings (20.6%). Pulmonary/critical care physicians experienced the highest number of patient-physician pairings (287, 50.6%). However, surgical critical care physicians had a higher median contact hours with their ARDS patients as compared to pulmonary critical care physicians (54.2 h vs. 48.0 h). The percentage of patients with severe ARDS was relatively consistent across the different physician groups, ranging from 19.2% for pulmonary/critical care to 26.3% for cardiology (Additional File, Supp Table 3 ). There were no significant differences in the distribution of ARDS severity seen by physicians in different specialties (Additional File, Supp Fig. 1 ).

Metric robustness

Our ARDS recognition metric showed no correlation with PBW, hypoxemia, or mortality proportion (Additional File, Supp Fig. 2 ).

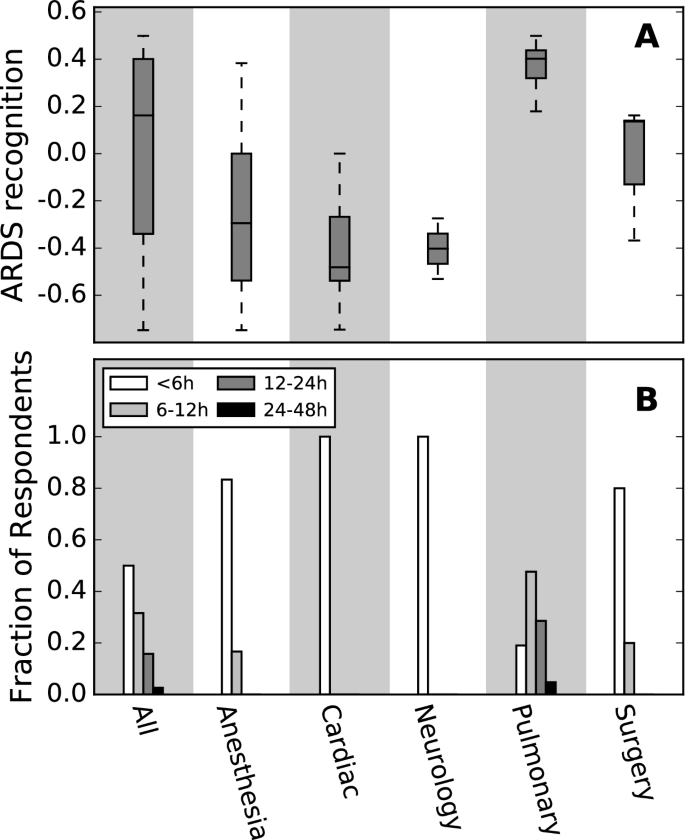

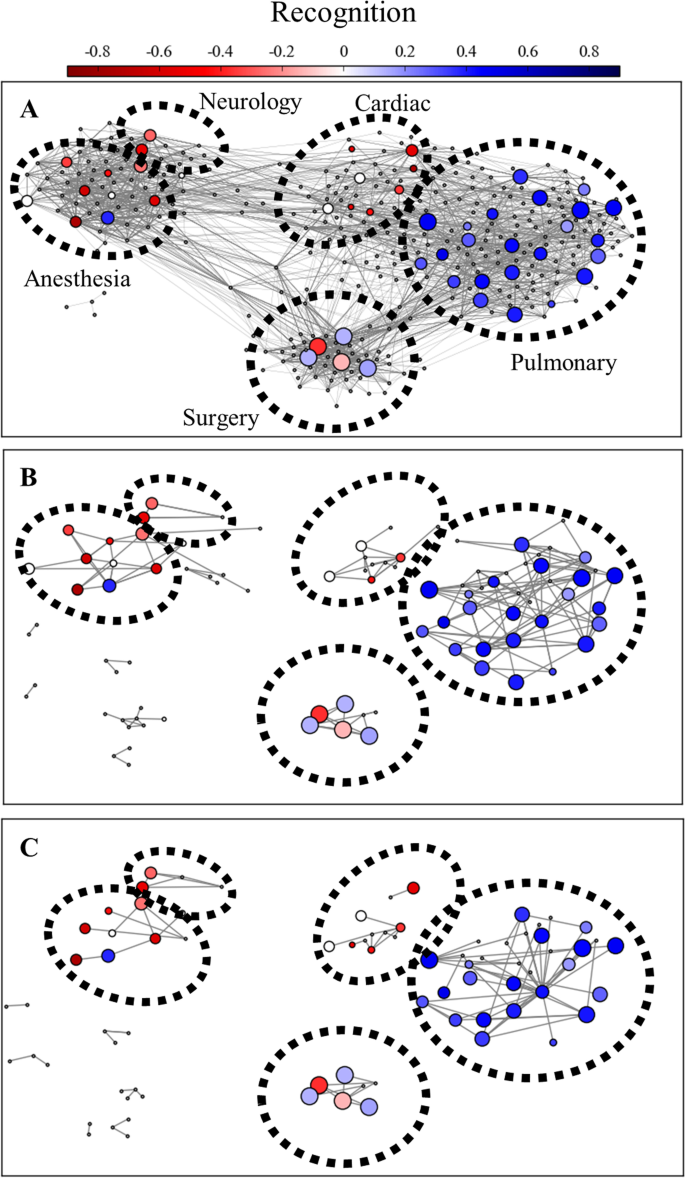

Pulmonary and critical care (PCCM) training showed a significant association with higher recognition (β = 0.63, 95% confidence interval 0.46–0.80, p < 7 × 10 − 5 , Fig. 3 A). PCCM training was not correlated with a higher number of ARDS patients; those with surgical critical care training cared for the most ARDS patients in our cohort. The patient contact, friendship, and innovation networks are shown in Fig. 4 . No positional metric for any network showed any association with recognition. None of the individual survey questions showed a significant association between specific answers and physician recognition.

Comparison of ARDS recognition and reported ARDS data wait times between specialties. A) Pulmonary and critical care medicine physicians (PCCM) recognize more ARDS patients than their non-PCCM colleagues. B) PCCM physicians report longer times (hours) to receipt of all data necessary to diagnose ARDS than non-PCCM physicians.

Interaction networks for physicians. Formal interaction networks (A) are based on shared ICU patient care events as determined by attending physician notes. Friendship (B) and opinion-leader (C) networks are built from critical care physicians’ survey responses in which they named colleagues who were considered friends or innovators, respectively. Each circle indicates an individual physician. Marker position is kept constant across network diagrams. Size of marker represents number of ARDS patients cared for by the physician. Color of marker indicates recognition performance (colorbar).

Since PCCM training was associated with increased recognition, physicians were split into two groups – those with PCCM training and all others – and their survey responses were evaluated for group differences. The only question that showed a statistically significant difference between PCCM and non-PCCM physicians was: “How long does it usually take from the time a patient clinically develops ARDS to the time you receive all the information needed to make a diagnosis of ARDS?” ( p < 5 × 10 − 4 ). Answer options were: < 6 h, 6–12 h, 12–24 h, 24–48 h, and > 48 h. PCCM physicians reported a longer time to ARDS diagnosis as compared to physicians on other teams (6–12 h vs. < 6 h, Fig. 3 B). There were no physicians outside the PCCM team that reported ARDS diagnosis times longer than 12 h, with the majority of the non-PCCM physicians reporting < 6 h to ARDS diagnosis (Fig. 3 B). The survey included additional systems-specific questions regarding the timing of individual data points (time to lab results, time to chest x-ray results, etc) as well as team-based communication questions, all of which showed no difference in the answers between PCCM physicians and non-PCCM physicians.

Study limitations

There are potential limitations to our study that may reduce its generalizability. First, our data was extracted from a single large academic hospital located in a major urban area; the other three centers were smaller, community-based hospitals where data was not collected over the full course of a patient’s stay. Our specific results may not generalize to clinician working at hospitals that differ in one or more of those characteristics. However, we believe that our approach would still be valid for other institutions since it accounts for both patient demographics and institutional setting.

Second, the majority of the networks were built using self-reported interactions, which are potentially biased by subjective reporting. However, the results did not change between directed and undirected networks or when we used the patient contact network for physicians, reducing the potential impact of this bias.

Third, we only built four different network types, which may, or may not, represent the communication network by which physicians would seek advice on ARDS recognition and/or LTVV implementation [ 46 ]. It is possible that our lack of association between ARDS recognition and any social network position metric is not a true lack of association, but instead a result of our inability to capture the correct network.

Finally, we did not ask survey respondents to rank barriers with respect to each other, so it is possible that our results concerning the time to obtain all information for an ARDS diagnosis are capturing a heterogenous experience under a single answer. This effect is mitigated by the fact that the question with differences between physician groups actually uses specific time frames, asking the respondents to quantify the delay in receiving the data needed to diagnose ARDS and that no differences were detected when looking at issues with obtaining particular types of data.

Increasing the timely adoption of evidence-based practices is a challenge faced by many industries employing highly-educated professionals such as medicine. In clinical medicine, this challenge is further complicated by the fact that adoption of evidenced-based practices is the two-step process of diagnosis followed by treatment. While missed or delayed diagnoses are important for quality of patient care, these incidents also have an impact on our ability to evaluate the adoption of evidence-based practices. A missed diagnosis is not the same as lack of knowledge about the innovation, or as resistance or refusal to use an evidence-based therapy. It, thus, requires a distinct intervention strategy.

Furthermore, the difficulty of diagnosing a specific disease is not the same patient to patient, with some cases presenting more clearly than others. This two-step adoption process combined with variable diagnosis difficulty makes it incredibly hard to compare the use of evidence-based practices between two physicians (or the same physician over time). In this work, we demonstrate a novel disease recognition metric that accounts for variability in patient disease severity and then use this metric to explore the relationships between acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) recognition and ICU physician characteristics (demographics, social network position, and survey results).

We found that physician training background was strongly associated with ARDS recognition, specifically those physicians trained in pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) recognized ARDS most often. While ARDS is a critical care syndrome, it is primarily a pulmonary condition, and thus it is plausible that pulmonary specialization primes physicians to recognize ARDS. Supporting the hypothesis that training background is a driving factor, we found that those with cardiology training, which does not include critical care certification, comprised the lowest performing group. While the pulmonary and critical care physicians had the most ARDS patient physician pairings, the second highest performing specialty (surgical critical care) had the highest number of ARDS patient contact hours. These results suggest that priming may have an effect on physician ARDS recognition.

Our analyses also uncovered that pulmonary/critical care physicians were more likely to report waiting longer times for receipt of all data necessary for ARDS recognition. PCCM physicians were the only physicians to report any delay greater than 12 h, with 88% of non-PCCM physicians reporting the best possible answer of < 6 h. This finding can be rationalized by the fact that pulmonary/critical care physicians were the top performers: clinicians who are actively engaging with a process, such as ARDS diagnosis, are both more likely to perform well and to be more aware of problems with the recognition process, than clinicians who are less engaged.

Finally, our study found that, once we accounted for the effect of training background, an individual physician’s position within the social or professional networks is not associated with their ability to recognize ARDS. These results hold across all types of connections (advice-seeking, friendship, innovation, patient contact). While a physician’s network position was not associated ARDS recognition, physician communities were primarily composed of a single training background, with very little contact between different critical care specialties. This finding is consistent with prior literature that shows that physicians tend to form tightly knit communities that may calcify knowledge and practices [ 33 , 47 , 48 , 49 ].

These findings have important implications for the design of interventions and for their implementation. It is a common implementation strategy to survey clinicians about perceived barriers and then design an intervention focused on addressing the most commonly reported barrier [ 50 ]. Our findings provide evidence that varying levels of disease recognition and clinician engagement with an innovation should be accounted for when evaluating barriers to adoption. Those physicians whose primary barrier to adoption is disease recognition may provide unintentional false negatives to important survey items. Indeed, our initial survey study showed few perceived barriers to ARDS diagnosis and no consistent correlation between reported barriers or attitudes and evidence-based practice use [ 26 ].

Looking at our results collectively, we found compelling evidence for the existence of two distinct ICU physician populations at a single hospital. Members of these two populations face different challenges in recognizing ARDS. Pulmonary/critical care physicians recognize ARDS more consistently than their peers in other specialties and express concern about accessing the information needed to make this diagnosis. Non-pulmonary/critical care physicians are not able to recognize ARDS consistently and report no barriers in the diagnosis process. These differences suggest that an effective intervention strategy will have to involve distinct approaches for each population.

While our work provides actionable insights for improving ARDS recognition – and subsequent LTVV utilization – a major strength of our methodology is that it accounts for the complexity of the patient population, while remaining agnostic with regard to the specific condition. With this flexibility, our methods can be readily adapted to assess recognition of other complex disease states that have variable presentations, such as mental health disorders. This method allows for the differentiation between which patient-physician interactions constitute adoption opportunities and which interactions are simply disease under-recognition, addressing an important need for effective implementation science in the clinical medicine setting.

Availability of data and materials

A limited de-identified dataset representing the final cleaned data analyzed during the current study is available in the public repository managed by Northwestern University: https://doi.org/10.21985/n2-snqm-tk72 . Requests for the full data set including dates of admission, intubation, mortality, and full ventilator data will require approval of the Northwestern Institutional Review Board and should be submitted to the corresponding author ( [email protected] ). Full data will be made available for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data as set forth by the Northwestern Institutional Review Board ( https://irb.northwestern.edu/ ).

Abbreviations

Evidence-based practice

Low tidal volume ventilation

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Intensive care unit

Predicted body weight

Arterial partial pressure of oxygen / fraction of inspired oxygen

Ordinary least squares

Pulmonary and critical care medicine

Sussman S, Valente TW, Rohrbach LA, Skara S, Pentz MA. Translation in the health professions: converting science into action. Eval Heal Prof. 2006;29:7–32.

Article Google Scholar

Balas E, Boren S. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Yearb Med Informatics. 2000;2000:65–70.

Google Scholar

Rogers EM. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addict Behav. 2002;27:989–93.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion Interventions : the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cutts S, Talboys R, Paspula C, Ail D, Premphe EM, Fanous R. History of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. 2016;4:547–8.

Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Torres Acosta MA, Singer BD. Pathogenesis of COVID-19-induced ARDS: implications for an ageing population. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2002049.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Herridge MS, Moss M, Hough CL, Hopkins RO, Rice TW, Bienvenu OJ, et al. Recovery and outcomes after the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in patients and their family caregivers. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(5):725–38.

Chiumello D, Coppola S, Froio S, Gotti M. What’s next after ARDS: long-term outcomes. Respir Care. 2016;61:689–99.

Network ARDS. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–8.

Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, Hodgson CL, Munshi L, Walkey AJ, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European society of intensive care medicine/society of critical care medicine clinical practice guideline: mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1253–63.

Villar J, Blanco J, Añón JM, Santos-Bouza A, Blanch L, Ambrós A, et al. The ALIEN study: incidence and outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome in the era of lung protective ventilation. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1932–41.

Young MP, Manning HL, Wilson DL, Mette S, Riker RR, Leiter JC, et al. Ventilation of patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: has new evidence changed clinical practice? Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1260–5.

Needham DM, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez P, Dinglas VD, Sevransky JE, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, et al. Lung protective mechanical ventilation and two year survival in patients with acute lung injury: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;344:e2124.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Weinert CR, Gross CR, Marinelli WA. Impact of randomized trial results on acute lung injury ventilator therapy in teaching hospitals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1304–9.

Umoh NJ, Fan E, Mendez-Tellez P, Sevransky JE, Dennison CR, Shanholtz C, et al. Patient and intensive care unit organizational factors associated with low tidal volume ventilation in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1463–8.

Chen YF, Lim CK, Ruan SY, Jerng JS, Lin JW, Kuo PH, et al. Factors associated with adherence to low-tidal volume strategy for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome and their impacts on outcomes: an observational study and propensity analysis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:1158–68.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kalhan R, Mikkelsen M, Dedhiya P, Christie J, Gaughan C, Lanken PN, et al. Underuse of lung protective ventilation: analysis of potential factors to explain physician behavior. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:300–6.

Weiss CH, Baker DW, Weiner S, Bechel M, Ragland M, Rademaker A, et al. Low tidal volume ventilation use in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1515–22.

Needham DM, Yang T, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, Shanholtz C, Sevransky JE, et al. Timing of low tidal volume ventilation and intensive care unit mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective cohorts study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:177–85.

Spece LJ, Caldwell ES, Lindee S, Tull CLH. Rate of low tidal volume ventilation use remains low in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome despite improvement efforts at a single center. J Crit Care. 2018;44:72–6.

Rubenfeld GD, Cooper C, Carter G, Thompson BT, Hudson LD. Barriers to providing lung-protective ventilation to patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1289–93.

Mikkelsen ME, Dedhiya PM, Kalhan R, Gallop RJ, Lanken PN, Fuchs BD. Potential reasons why physicians underuse lung-protective ventilation: a retrospective cohort study using physician documentation. Respir Care. 2008;53:455–61.

Checkley W, Brower R, Korpak A, Thompson BT. Effects of a clinical trial on mechanical ventilation practices in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1215–22.

Weiss CH, Baker DW, Tulas K, Weiner S, Bechel M, Rademaker A, et al. A critical care clinician survey comparing attitudes and perceived barriers to low tidal volume ventilation with actual practice. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1682–9.

Bechel MA, Pah AR, Shi H, Mehrotra S, Persell SD, Weiner S, et al. A quantitative approach for the analysis of clinician recognition of acute respiratory distress syndrome using electronic health record data. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–16.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christakis NA, Asch DA. Physician characteristics associated with decisions to withdraw life support. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:367–72.

Valente T, Davis RL. Accelerating the diffusion of innovations using opinion leaders. Annu AAPSS. 1999;566:55–67.

Valente TW, Fosados R. Diffusion of innovations and network segmentation: the part played by people in promoting health. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:23–31.

Gesell SB, Barkin SL, Valente TW. Social network diagnostics: a tool for monitoring group interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8:116.

Palinkas LA, Holloway IW, Rice E, Fuentes D, Wu Q, Chamberlain P. Social networks and implementation of evidence-based practices in public youth-serving systems: a mixed-methods study. Implement Sci. 2011;6:113.

Mascia D, Cicchetti A, Damiani G. “Us and them”: a social network analysis of physicians’ professional networks and their attitudes towards EBM. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:429.

Kim DA, Hwong AR, Stafford D, Hughes DA, O'Malley AJ, Fowler JH, et al. Social network targeting to maximise population behaviour change: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;8:583–92.

Hunter RF, McAneney H, Davis M, Tully MA, Valente TW, Kee F. “Hidden” social networks in behavior change interventions. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:513–6.

Valente TW, Palinkas LA, Czaja S, Chu K, Brown CH. Social network analysis for program implementation. Plos One. 2015;10:e0131712.

Yousefi-Nooraie R, Dobbins M, Marin A, Hanneman R, Lohfeld L. The evolution of social networks through the implementation of evidence-informed decision-making interventions: a longitudinal analysis of three public health units in Canada. Implement Sci. 2015;10:1–12.

Glegg SMN, Jenkins E, Kothari A. How the study of networks informs knowledge translation and implementation: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2019;14:1–27.

Tang MY, Rhodes S, Powell R, McGowan L, Howarth E, Brown B, et al. How effective are social norms interventions in changing the clinical behaviours of healthcare workers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2021;16:1–19.

Newman MEJ. Networks: an introduction. 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Book Google Scholar

Wensing M, van der Eijk M, Koetsenruijter J, Bloem BR, Munneke M, Faber M. Connectedness of healthcare professionals involved in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: a social networks study. Implement Sci. 2011;6:1–8.

Guimerà R, Amaral LAN. Functional cartography of complex networks. Nature. 2005;433:895–900.

Barnett ML, Landon BE, O’Malley AJ, Keating NL, Christakis NA. Mapping physician networks with self-reported and administrative data. Health Serv Res. 2011;46:1592–609.

Poncela-Casasnovas J, Spring B, McClary D, Moller AC, Mukogo R, Pellegrini CA, et al. Social embeddedness in an online weight management programme is linked to greater weight loss. J R Soc Interface. 2015;12:20140686.

Colquhoun D. An investigation of the false discovery rate and the misinterpretation of P values. R Soc Open Sci. 2014;1:140216.

Valente TW, Pumpuang P. Identifying opinion leaders to promote behavior change. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:881–96.

Mascia D, Cicchetti A. Physician social capital and the reported adoption of evidence-based medicine: exploring the role of structural holes. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:798–805.

Yousefi-Nooraie R, Dobbins M, Brouwers M, Wakefield P. Information seeking for making evidence-informed decisions: a social network analysis on the staff of a public health department in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:118.

Bunger AC, Doogan N, Hanson RF, Birken SA. Advice-seeking during implementation: a network study of clinicians participating in a learning collaborative. Implement Sci. 2018;13:1–12.

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:1–12.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This project was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant T32GM008152 (MB); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Grant K23HL118139 and Grant R01HL140362-01A1 (CHW); the Francis Family Foundation (Parker B. Francis Fellowship Program, CHW); the Department of Defense Army Research Office, Grant W911NF-14-1-0259 (MB, LANA, CHW); the National Center for Research Resources, Grant 5UL1RR025741, which is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 8UL1TR000150 (Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Enterprise Data Warehouse); and John and Leslie McQuown (MB, LANA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Francis Family Foundation, or the Department of Defense. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Meagan Bechel

Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Road (Room E136), Evanston, IL, 60208, USA

Adam R. Pah & Luís A. Nunes Amaral

Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Adam R. Pah

Division of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Stephen D. Persell

Center for Primary Care Innovation, Institute for Public Health and Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA

Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy, and Immunology, NorthShore University HealthSystem, 1001 University Place, Suite 162, Evanston, IL, 60201, USA

Curtis H. Weiss

Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

Luís A. Nunes Amaral

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception or design: CHW, LANA, SDP; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data: MB, ARP, CHW, LANA; drafting of the manuscript: MB, CHW, LANA; revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content: all; final approval of the manuscript for submission: all.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Curtis H. Weiss or Luís A. Nunes Amaral .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved with a waiver of consent by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00098191). The clinician survey study was approved with a waiver of consent by Northwestern University (STU00208733) and participating hospitals. The ARDS patient cohort study was approved with a waiver of consent by Northwestern University (STU00208049). Administrative permissions and licenses were not required to access patient data.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

SP reports grant support from Pfizer, Inc. unrelated to this manuscript. MB, LANA, and CHW report the related US provisional patent: Systems and Methods for Patient Management Within a Healthcare Facility. US Serial No: 62/457,574. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Bechel, M., Pah, A.R., Persell, S.D. et al. The first step is recognizing there is a problem: a methodology for adjusting for variability in disease severity when estimating clinician performance. BMC Med Res Methodol 22 , 69 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01543-7

Download citation

Received : 24 October 2021

Accepted : 11 February 2022

Published : 16 March 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01543-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Clinical medicine

- Performance measure

- Data science

- Social network analysis

- Critical care

BMC Medical Research Methodology

ISSN: 1471-2288

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The Art of Effective Problem Solving: A Step-by-Step Guide

Author: Daniel Croft

Daniel Croft is an experienced continuous improvement manager with a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt and a Bachelor's degree in Business Management. With more than ten years of experience applying his skills across various industries, Daniel specializes in optimizing processes and improving efficiency. His approach combines practical experience with a deep understanding of business fundamentals to drive meaningful change.

Whether we realise it or not, problem solving skills are an important part of our daily lives. From resolving a minor annoyance at home to tackling complex business challenges at work, our ability to solve problems has a significant impact on our success and happiness. However, not everyone is naturally gifted at problem-solving, and even those who are can always improve their skills. In this blog post, we will go over the art of effective problem-solving step by step.

You will learn how to define a problem, gather information, assess alternatives, and implement a solution, all while honing your critical thinking and creative problem-solving skills. Whether you’re a seasoned problem solver or just getting started, this guide will arm you with the knowledge and tools you need to face any challenge with confidence. So let’s get started!

Problem Solving Methodologies

Individuals and organisations can use a variety of problem-solving methodologies to address complex challenges. 8D and A3 problem solving techniques are two popular methodologies in the Lean Six Sigma framework.

Methodology of 8D (Eight Discipline) Problem Solving:

The 8D problem solving methodology is a systematic, team-based approach to problem solving. It is a method that guides a team through eight distinct steps to solve a problem in a systematic and comprehensive manner.

The 8D process consists of the following steps:

- Form a team: Assemble a group of people who have the necessary expertise to work on the problem.

- Define the issue: Clearly identify and define the problem, including the root cause and the customer impact.

- Create a temporary containment plan: Put in place a plan to lessen the impact of the problem until a permanent solution can be found.

- Identify the root cause: To identify the underlying causes of the problem, use root cause analysis techniques such as Fishbone diagrams and Pareto charts.

- Create and test long-term corrective actions: Create and test a long-term solution to eliminate the root cause of the problem.

- Implement and validate the permanent solution: Implement and validate the permanent solution’s effectiveness.

- Prevent recurrence: Put in place measures to keep the problem from recurring.

- Recognize and reward the team: Recognize and reward the team for its efforts.

Download the 8D Problem Solving Template

A3 Problem Solving Method:

The A3 problem solving technique is a visual, team-based problem-solving approach that is frequently used in Lean Six Sigma projects. The A3 report is a one-page document that clearly and concisely outlines the problem, root cause analysis, and proposed solution.

The A3 problem-solving procedure consists of the following steps:

- Determine the issue: Define the issue clearly, including its impact on the customer.

- Perform root cause analysis: Identify the underlying causes of the problem using root cause analysis techniques.

- Create and implement a solution: Create and implement a solution that addresses the problem’s root cause.

- Monitor and improve the solution: Keep an eye on the solution’s effectiveness and make any necessary changes.