Case Studies in Workplace Safety: Real-Life Examples of Successful Safety Initiatives

Introduction

Workplace safety is not just about compliance; it’s about saving lives, preventing injuries, and creating a culture of well-being. To illustrate the power of successful safety initiatives, we’ll dive into real-life case studies where organizations have gone above and beyond to ensure the safety of their employees. These inspiring stories showcase how proactive safety measures can lead to reduced incidents, improved morale, and enhanced overall productivity.

1. Tesla’s “Safety First” Culture

Tesla, the electric vehicle pioneer, places a strong emphasis on workplace safety. The company has developed a comprehensive “Safety First” culture, which goes beyond just meeting regulatory requirements. Tesla’s initiative includes rigorous safety training, daily huddles to discuss safety concerns, and a proactive approach to addressing any issues.

Result: Tesla has seen a steady decrease in workplace incidents and an increase in employee engagement. Their safety culture not only protects workers but also reinforces the organization’s commitment to innovation and excellence.

2. Alcoa’s Transformation Through Safety

Alcoa, a global aluminum manufacturer, underwent a significant transformation in the 1980s under the leadership of Paul O’Neill. O’Neill made safety the company’s top priority. His philosophy was simple: “If you want to improve safety, you have to improve everything.”

Result: Alcoa’s safety initiative not only led to a remarkable reduction in workplace injuries but also significantly boosted productivity and profitability. By focusing on safety, the company transformed its entire organizational culture.

3. DuPont’s STOP Program

DuPont, a multinational chemical company, introduced the STOP (Safety Training Observation Program) initiative to empower employees at all levels to identify and report safety hazards. The program encourages workers to speak up, and it trains them to spot potential dangers in the workplace.

Result: DuPont’s STOP Program led to a dramatic decrease in accidents and injuries. It also fostered a culture of transparency and accountability, where every employee played a vital role in ensuring their safety.

4. The Massachusetts General Hospital’s “Safety Matters” Campaign

Healthcare organizations are not exempt from the importance of workplace safety. The Massachusetts General Hospital initiated the “Safety Matters” campaign to reduce medical errors and ensure the safety of patients and healthcare workers.

Result: By emphasizing the importance of safety protocols and encouraging communication among staff, the hospital saw a significant reduction in patient safety incidents and workplace injuries. The “Safety Matters” campaign not only saved lives but also improved the quality of patient care.

5. Singapore Airlines’ Safety Excellence

In the aviation industry, safety is paramount. Singapore Airlines is a shining example of a company that prioritizes safety. The airline invests heavily in safety training and has a robust reporting system that encourages employees to report safety concerns without fear of reprisals.

Result: Singapore Airlines’ relentless commitment to safety has led to an impeccable safety record and a strong reputation for being one of the world’s safest airlines. Passengers and employees alike can feel confident in their commitment to safety.

These real-life case studies demonstrate that a proactive approach to workplace safety not only saves lives but also has a positive impact on an organization’s bottom line. Successful safety initiatives are not merely a box-ticking exercise; they are a reflection of an organization’s values and a commitment to the well-being of its employees. By learning from these examples, we can inspire a culture of safety in our own workplaces and reap the benefits of reduced incidents, improved morale, and increased productivity.

- Magazine Subscription

- ENewsletters

- EHS Education

- Safety Leadership Conference

- America's Safest Companies

- Search Search

- Members Only

- Environment

- Safety Technology

- Training & Engagement

- Safety Leadership

How Did They Do That? Case Studies on EHS Excellence

While it might be an overused phrase — “no need to reinvent the wheel” — there is a lot to be learned from others who have tackled and found solutions to safety issues that many companies face.

In this vein, the winners of the Campbell Award offer materials including business case studies, teaching notes and case study presentations.

Frist a word about the award, which is a National Safety Council award. Its mission is to “identify and provide evidence-based findings that enable current and future business leaders to effectively advance business vitality through embracing the value of environmental, health and safety management.” The award is supported by a network of Global Partners across five continents.

The Campbell Award recognizes organizations for commendable leadership and excellence in integrating EHS management with business operations systems. The award aims to:

- Establish a validated process by which organizations can measure the performance of their EHS operations system against well tested and internationally accepted key performance indicators.

- Capture and evaluate the successes and lessons learned through a rigorous systematic review process.

- Foster the sharing of leading-edge EHS management systems and best practices for educational purposes worldwide.

- Recognize organizations that have EHS well integrated as a key business value and in which measurable achievements in EHS performance are productive and profitable.

Here are some samples (and excerpts) of these case studies:

Johnson & Johnson -- Social Responsibility & Sustainable Competitive Advantages

This business case study starts with the assumption that EHS is a core value — because, for them, it is. Johnson & Johnson’s leaders, however, are aware that this belief is not shared by everyone — including some of its shareholders, who may be more focused on profit margin. By examining the company's credo-based culture and a number of its key EHS initiatives, Johnson & Johnson wanted students to come to understand the myriad ways in which social responsibility offers the company a truly sustainable competitive advantage.

Alcan- Leadership Challenges in Cross-Culture Ventures

This business case study takes a well-developed integrated EHS management system and puts it to the test in an extreme physical and cultural environment. In examining the astonishing results at the Ningxia facility, Alcan leadership wanted students to understand the difference an integrated, transferable system can make. Through this remarkable example, students come to see the value of integration and transfer as it extends not only to the business but the wider community — making the decision they’re faced with at the end of the study even more crucial.

Dow—Inseparability of Safety

“If you can’t do it better, why do it?” These famous words of Dow Chemical Company founder Herbert H. Dow begin the organization’s Campbell Award Case Study. It is this history of innovation, coupled with aspirational goal-setting and world-class expertise, which has enabled Dow to continue to reach and exceed its vision. In this study, readers gain insight into Dow’s transformational goal development process, including a look at incentives, empowerment, risk assessment, leading indicators, and more. Readers have the opportunity to put themselves in the shoes of Dow leadership and ask themselves, “What should we do next?”

More examples can be found here .

There is also a Campbell Institute that was launched from the Campbell Award winners as well as thought-leaders from the National Safety Council. The mission of the Institute is to help organizations achieve and sustain EHS excellence through participation, research and events.

Adrienne Selko | Senior Editor

Email [email protected]

Adrienne Selko is also the senior editor at Material Handling and Logistics and is a former editor of IndustryWeek.

Continue Reading

Johnson & Johnson Takes Worldwide Approach to Ergonomics

NSC: Award Winner Puts EHS First

Sponsored recommendations.

Free Webinar: ISO 45001 – A Commitment to Occupational Health, Safety & Personal Wellness

ISO 45003 – Psychological Health and Safety at Work

DH Pace, national door and dock provider, reduces TRIR and claims with EHS solution

Case Study: Improve TRIR from 4+ to 1 with EHS Solution and Safety Training

Voice your opinion, to join the conversation, and become an exclusive member of ehs today, create an account today.

DOL Mine Inspections Result in Significant Violations

Emergency Responder Standards, Heat Stress and Training Tactics: What You’re Reading This Month

Safety Leadership Conference 2024 to Co-locate with VPPPA’s Safety+

SLC 2024 Preview: The 4 Keys to a World-Class Safety Culture

Photo Gallery: Photos from the Deadly Yarnell Hill Fire

6 Steps to Build Leadership Buy-In for EHS Technology

6 Qualities That Make a Safety Leader

Soft Skills 101: Three Essential Personal Attributes for Safety Professionals

OSHA's most interesting cases

What happened – and lessons learned.

Every OSHA investigation offers an opportunity for using what comes to light to help prevent similar incidents.

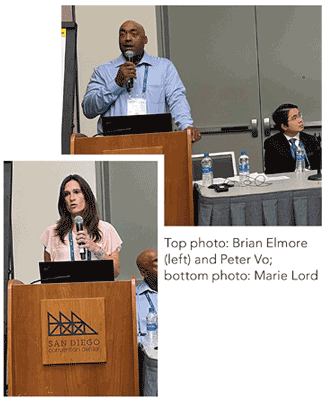

At the 2022 NSC Safety Congress & Expo in September, OSHA staffers highlighted three investigations – and the lessons learned – during the agency’s “Most Interesting Cases” Technical Session.

- Brian Elmore , an OSHA inspector based in Omaha, NE

- Marie Lord , assistant area director of the OSHA office in Marlton, NJ

- Peter Vo , safety engineer in OSHA’s Houston South area office

Here are the cases they presented.

- Shelving collapse in a cold storage warehouse

- Lockout/tagout-related amputation

- Crane collapse

Related Articles

More of osha’s ‘most interesting cases’, post a comment to this article.

Safety+Health welcomes comments that promote respectful dialogue. Please stay on topic. Comments that contain personal attacks, profanity or abusive language – or those aggressively promoting products or services – will be removed. We reserve the right to determine which comments violate our comment policy. (Anonymous comments are welcome; merely skip the “name” field in the comment box. An email address is required but will not be included with your comment.)

Report Abusive Comment

Why Safety Culture Improvement Matters: Case Studies

By Josh Williams, Ph.D.

There is a large body of evidence showing the benefits of safety culture advancement including improved: safety motivation and participation (Neal & Griffin, 2006), employee commitment (Clarke, 2006), perceptions of leadership buy-in (Brown & Holmes, 1986), and other organizational factors like job satisfaction, likelihood of staying with the job, and decreased stress (Morrow & Crum, 1988). I would like to share a few examples of client case studies showing why safety culture improvement matters.

Improving safety culture is also associated with fewer workplace injuries (Barling et al., 2002; Clarke, 2006; Gillen et al., 2002; Zohar, 2000, 2002). There is no single metric to describe how long it will take incidents to reduce after a change effort because every company and every culture are different. There are variables that influence changes in target outcomes including the size of the company (e.g., Scott, 1998), the industry and sector of the company (e.g., Hoonakker et al., 2005), the maturity of the culture at the onset of the change process (e.g., Kezar, 2001), the amount of time the organization spends on the development effort (e.g., Weick & Quinn, 1999), how comprehensive the change efforts are (e.g., Krause et al., 1999), and the effectiveness of safety culture improvement interventions.

Improving safety culture takes smart planning, effort, and long-term commitment. Here are a few examples of client case studies showing how safety culture advancement helps prevent incidents.

Unpacking the Importance of Safety Culture: Insightful Case Studies

Case study 1: power generation facility.

Propulo partnered with a large coal mine and power generation facility to help improve safety culture. In the shadow of a large-scale transition away from coal, they engaged Propulo to improve safety awareness and performance. Recognizing the disruptive impact of the transition away from coal, Propulo focused on understanding the degree to which change had affected the workers’ focus on safety. Targeting points of pain between leadership and the frontline workforce, we sought to create a more cohesive workplace which could facilitate more evolved safety conversation.

After initial scoping to understand the dynamics of their safety culture, we delivered person-based (e.g., attitudes and behavior) safety training, conducted safety leadership ownership activities, and provided guidance on process improvements for safety inspections, meetings, job planning, corporate communications, and change management. This resulted in a 38% reduction in TRIR and more than 900,000 exposure hours without an injury – the longest stretch in company history.

Case Study 2: Energy Provider

Propulo partnered with a very large energy provider to develop a customized and targeted safety program to reduce injuries. This organization had a vertically integrated operation across production, trading, and retail, and also used a variety of generation technologies like natural gas, LPG, hydro, wind, and thermal. Given their broad operational variety and the challenges that accompany vertical integration , our team focused on understanding how to address each of the diverse subcultures within their organization. We provided safety leadership and field level safety training and coaching that was customized for each group along with focused programs to provide structure for supporting this training. Targeted training is considerably more effective when paired with structural changes which permit the embedding of training concepts and learning transfer. This led to an 89% reduction in total recordables, a 55% decrease in lost time incidents, and a more than 1,000% reduction in average compensations claim costs (relative to the national average).

Case Study 3: Canadian Mining Company

Propulo worked with new ownership of a leading Canadian diamond mining company to assess their safety culture maturity, increase safety engagement, and improve overall safety performance. This organization was struggling with a perceived lack of a unified safety vision, noncompliance with site policies, low levels of hazard identification and risk awareness, and subpar leadership capabilities among some team leaders. Also, there was a lack of personal accountability and belief that employees should look out for one another.

Propulo partnered with this organization to:

- Establish a steering team to guide the change effort.

- Support a communication strategy to personalize safety messaging that employees would “feel” as a value instead of just another company program.

- Identify and train process champions across departments who would serve as leaders in their respective community to support the change effort.

- Implement a safety culture leadership training strategy to all site leaders, from executives to frontline supervisors.

- Deliver safety culture and ownership training to all employees.

- Develop a sustainment strategy that included embedding training concepts in safety meetings and pre-job briefs, implementing monthly safe production communication themes, and developing a visual campaign to reinforce safe production values.

- Support executive messaging to better align corporate communications and reinforce the message that “safe mining” is what we do and not just a corporate goal.

Over this two-year period, the organization was able to reduce total recordable rates from 4.17 to 1.1 which was one of the lowest in the Canadian mining industry (average was 3.28).

Managing Expectations

It is important to understand that changes in lagging safety indicators (incidents, injuries, property damage) typically lag safety culture improvements. Although the trend is that companies will enjoy a gradual decrease in injuries across several years after implementing quality safety improvement programs, the effects of change on safety outcomes do not happen in a predictable fashion (a straight line). Across a multi-year time period, there will likely be years where there is a steeper reduction in injuries, while other years could more steadily decline or plateau. For example, Krause et al. (1999) studied the effect of behavior-based safety management changes on injury reduction over time in 73 companies. Results showed the change was weakest (on average) in the earlier time periods and were the strongest at year five (i.e., five years after the interventions were completed). So, it is reasonable to expect that culture change takes time, some of the strongest effects may be seen after several years, and the results won’t be a linear and consistent trend.

The end game for conscientious leaders is to decrease the quantity and severity of incidents and injuries. Improving safety culture has been demonstrated to reduce the likelihood of these events occurring, even if it doesn’t follow a predictable path or happen overnight. Conducting safety culture assessments with strategic planning, delivering safety leadership skills training and coaching, and providing ongoing executive coaching are just a few ways that Propulo can help leaders improve safety culture to prevent serious injuries and fatalities and other incidents.

Case Study: BBS (Behavior-Based Safety) 2.0

Improve Your Safety Systems

RELATED POSTS

Change Management for Safety Derailers: Look Out for These Red Flag Conditions

A Novel Way to Incentivize Safety: Case Study

Improving Safety Leadership: Leading with Emotional Intelligence

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 14 Jul 2022

- Research & Ideas

When the Rubber Meets the Road, Most Commuters Text and Email While Driving

Laws and grim warnings have done little to deter distracted driving. Commuters routinely use their time behind the wheel to catch up on emails, says research by Raffaella Sadun, Thomaz Teodorovicz, and colleagues. What will it take to make roads safer?

- 15 Mar 2022

This Workplace Certification Made Already Safe Companies Even Safer

New research by Michael Toffel and colleagues confirms what workplace safety advocates have long claimed: Adopting OHSAS 18001 reduces worker injuries and improves a brand's image. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Aug 2021

Can Autonomous Vehicles Drive with Common Sense?

Driverless vehicles could improve global health as much as the introduction of penicillin. But consumers won't trust the cars until they behave more like humans, argues Julian De Freitas. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Sep 2019

- Cold Call Podcast

How a New Leader Broke Through a Culture of Accuse, Blame, and Criticize

Children’s Hospital & Clinics COO Julie Morath sets out to change the culture by instituting a policy of blameless reporting, which encourages employees to report anything that goes wrong or seems substandard, without fear of reprisal. Professor Amy Edmondson discusses getting an organization into the “High Performance Zone.” Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 11 Jun 2019

- Working Paper Summaries

Throwing the Baby Out with the Drinking Water: Unintended Consequences of Arsenic Mitigation Efforts in Bangladesh

In this study, households that were encouraged to switch water sources to avoid arsenic exposure experienced a significant rise in infant and child mortality, likely due to diarrheal disease from exposure to unsafe alternatives. Public health interventions should carefully consider access to alternatives when engaging in mass behavior change efforts.

- 31 Jan 2019

How Wegmans Became a Leader in Improving Food Safety

Ray Goldberg discusses how the CEO of the Wegmans grocery chain faced a food safety issue and then helped the industry become more proactive. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 09 May 2018

A Simple Way for Restaurant Inspectors to Improve Food Safety

Basic tweaks to the schedules of food safety inspectors could prevent millions of foodborne illnesses, according to new behavioral science research by Maria Ibáñez and Michael Toffel. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Sep 2016

What Brands Can Do to Monitor Factory Conditions of Suppliers

For better or for worse, it’s fallen to multinational corporations to police the overseas factories of suppliers in their supply chains—and perhaps make them better. Michael W. Toffel examines how. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Jun 2016

Companies Need to Start Marketing Security to Customers

The recent tragedies in Orlando underscore that businesses and their customers seem increasingly vulnerable to harm, so why don't companies do and say more about security? The ugly truth is safety doesn't sell, says John Quelch. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jan 2016

The Integrity of Private Third-party Compliance Monitoring

Michael Toffel and Jodi Short examine how conflict of interest and other risks lead to inaccurate monitoring of health, labor, and environmental standards.

- 21 May 2012

OSHA Inspections: Protecting Employees or Killing Jobs?

As the federal agency responsible for enforcing workplace safety, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration is often at the center of controversy. Associate Professor Michael W. Toffel and colleague David I. Levine report surprising findings about randomized government inspections. Key concepts include: In a natural field experiment, researchers found that companies subject to random OSHA inspections showed a 9.4 percent decrease in injury rates compared with uninspected firms. The researchers found no evidence of any cost to inspected companies complying with regulations. Rather, the decrease in injuries led to a 26 percent reduction in costs from medical expenses and lost wages—translating to an average of $350,000 per company. The findings strongly indicate that OSHA regulations actually save businesses money. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Jan 2011

Terror at the Taj

Under terrorist attack, employees of the Taj Mahal Palace and Tower bravely stayed at their posts to help guests. A look at the hotel's customer-centered culture and value system. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Request Membership

Latest Articles

Workplace Fire Safety: Essential Strategies for a Safer Office

Comprehensive Guide to Fire Safety: Strategies for Prevention and Protection

Continual Professional Development (CPD) in Health, Safety, and Environment (HSE): A Guide for Ongoing Excellence

Preparing a Risk Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide

Creating an Effective Fire Response Plan for Your Office

Fire Safety Training: Empowering Employees for Emergency Situations

Office Fire Hazards: Identifying and Mitigating Risks

The Role of Fire Drills in Ensuring a Safe Workplace

Navigating Workplace Fire Safety: Essential Tips for Employees

Case studies in construction safety: lessons learned from real incidents.

Case studies in construction safety provide invaluable insights into real incidents, helping to understand the consequences of safety lapses and the importance of preventive measures. Here are summaries of some impactful case studies, highlighting key lessons learned:

Case Study 1: Structural Collapse Due to Inadequate Shoring

- Incident : A multi-story building under construction collapsed due to inadequate shoring and bracing during the concrete curing process.

- Consequences : Multiple injuries and fatalities occurred, along with significant project delays and financial losses.

- Lessons Learned : The importance of adhering to engineering specifications for temporary structures and the need for regular inspections by qualified personnel.

Case Study 2: Electrocution from Overhead Power Lines

- Incident : A worker operating a crane came into contact with overhead power lines, resulting in electrocution and death.

- Consequences : Loss of life, legal action against the company, and significant financial settlements.

- Lessons Learned : The critical need for hazard assessment regarding overhead power lines and the importance of safety training for equipment operators.

Case Study 3: Trench Collapse

- Incident : A trench collapse occurred due to a lack of proper shoring and trench boxes, trapping workers.

- Consequences : Fatalities and serious injuries, alongside OSHA fines and criminal charges.

- Lessons Learned : The vital role of following trench safety guidelines, including proper shoring and having a trench rescue plan in place.

Case Study 4: Fall from Height Due to Inadequate Fall Protection

- Incident : A worker fell from a significant height due to inadequate fall protection measures.

- Consequences : Fatal injury, increased insurance premiums, and significant OSHA fines.

- Lessons Learned : The necessity of fall protection systems for work at height and regular safety training on their use.

Case Study 5: Fire and Explosion Due to Chemical Mishandling

- Incident : Incorrect storage and handling of flammable chemicals led to a major fire and explosion.

- Consequences : Severe injuries, property damage, and long-term environmental impact.

- Lessons Learned : The importance of proper chemical storage, handling procedures, and emergency response planning.

Case Study 6: Scaffolding Failure Due to Overloading

- Incident : Scaffolding collapsed under the weight of too many workers and equipment.

- Consequences : Multiple injuries and a halt in construction activities.

- Lessons Learned : Adherence to load capacity guidelines for scaffolding and regular safety checks.

Case Study 7: Health Issues from Prolonged Exposure to Hazardous Materials

- Incident : Workers developed chronic respiratory issues from prolonged exposure to asbestos and silica without proper PPE.

- Consequences : Long-term health problems for workers, lawsuits, and compensation claims.

- Lessons Learned : The necessity of providing adequate PPE and training workers on handling hazardous materials.

These case studies underscore the multifaceted nature of construction safety, emphasizing the need for comprehensive safety management systems. They highlight the importance of adhering to safety protocols, continuous training, and proactive risk management to prevent accidents and protect workers. By learning from these incidents, construction managers can better prepare and mitigate similar risks in their projects.

You May Also Like

More From Author

+ there are no comments, cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Safety First: Implementing a Culture of Safety in Construction

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Essentials for Every Construction Worker

You may also like:.

EHS Daily Advisor

Practical EHS Tips, News & Advice. Updated Daily.

Injuries and Illness

Case studies in safety: a great training tool.

Updated: Nov 6, 2011

Case studies are a great safety training tool. It’s like CSI. Employees can really get involved examining the evidence and seeing why an accident occurred.

Safety case studies are fun, challenging, interactive, and a highly effective training method.

Armed with the knowledge they gain from examining the facts of real workplace accidents, workers can learn how to avoid similar incidents and injuries.

Here’s an example of such a case from BLR’s OSHA Accident Case Studies . This case is about a confined space incident.

The Incident

Two employees arrived at concrete pit at demolition site where they’d been working to salvage the bottom part of a cardboard baler imbedded in the pit. When the employees uncovered the pit, they both felt a burning sensation in their eyes.

Employee #1 climbed down into the pit to determine what might be causing their eyes to burn. He immediately climbed back out of the pit because it was hot. He decided to put a water hose into the pit to help cool it down.

The employees climbed down into the pit with the water hose. Both employees experienced chest tightness, difficulty breathing, and burning eyes. They decided to exit the pit because of the intolerable conditions.

Employee #2 climbed out first. As Employee #1 was climbing the ladder to get out, he was overcome by the fumes and fell back into the pit. He landed on his back, unconscious.

Employee #2 climbed down into the pit in an attempt to rescue employee #1, but was unable to lift him. Employee #2 exited the pit in order to get help. Unfortunately, by the time help arrived, Employee #1 had died of asphyxiation.

The accident investigation determined that employee #1 had attempted to extinguish a small cutting torch fire the day before by covering it with sand and dirt. Apparently the fire was not extinguished and smoldered overnight, which resulted in a build up of carbon monoxide inside the pit.

Try OSHA Accident Case Studies and give a boost to your safety training program with real-life case studies of actual industrial accidents from OSHA files. We have a great one on lifting. Get the details.

Discussion Questions

Once the case has been presented, some discussion questions can help kick off the analysis of the incident. For example:

- What are the potential hazards of confined spaces?

- What was the specific hazard in this case that cause a fatality?

- Were these workers properly trained and equipped to enter a confined space?

- What type of air monitoring should be done before entering a confined space?

- Was this a permit-required confined space? If so, were the workers familiar with the safety requirements of the permit?

- Was confined space rescue equipment readily accessible?

- Training? There is no indication on the accident report that the employees were trained as authorized entrants of confined spaces. If they did receive any confined space entry training, they clearly didn’t apply what they learned. Authorized entrants are trained on the hazards of confined spaces, atmosphere testing procedures, symptoms of lack of oxygen or exposure to toxic chemicals, personal protective equipment (PPE), communication equipment, rescue retrieval equipment, etc.

- Hazard warning? These employees entered the space despite experiencing "red flags," such burning eyes and unusual heat. An important part of training for confined space workers includes learning about hazards such as the symptoms of a lack of oxygen or exposure to toxic chemicals. Workers should never enter a space, and should immediately leave a space, in which they experience signs of hazardous conditions.

Even your most skeptical workers will see what can go wrong and become safety-minded employees with OSHA Accident Case Studies . They’ll learn valuable safety training lessons from real mistakes—but in classroom training meetings instead of on your shop floor. Get more info.

- Permit-required? Most confined spaces require a permit before workers can enter the space. Permit-required confined spaces have the potential for hazards such as hazardous atmospheres, engulfment, entrapment, falls, heat, combustibility, etc. By reviewing a permit, entrants know they have obtained all the necessary equipment and the atmosphere has been monitored so they know the space is safe to enter.

- Testing? This worker died of asphyxiation, or lack of oxygen. If the atmosphere in the pit had been tested prior to entry, this accident would not have occurred. Common monitoring practices require a check of the oxygen concentration, a check for flammable gases or vapors (especially important if welding is going to be done in the space), and finally, a check for any other toxic chemicals known to potentially be in the space. Monitoring is conducted before entering the space and periodically while workers are in the space.

- Rescue procedures and equipment? The worker who collapsed back into the pit while climbing out could not be rescued because he was not wearing required rescue equipment. He should have been wearing a full-body harness attached to a retrieval line that was connected to a winch-type system that could have been used to pull the unconscious worker out of the pit. Of course, the other employee would have had to have been trained in confined space rescue procedures.

Tomorrow, we’ll introduce you to another case from OSHA Accident Case Studies, this one about a materials handling accident that resulted in a serious back injury.

More Articles on Injuries and Illness

1 thought on “case studies in safety: a great training tool”.

PingBack from http://savant7.com/workaccidentreport/workplace-safety/case-studies-train-employees-to-look-for-accident-causes-and-prevention/

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Case studies

Successful leadership.

There are many benefits to be gained from successful leadership in health and safety, as these case studies show.

Case study - North Staffordshire Combined Healthcare NHS Trust

The board found itself facing service improvement targets. Using new corporate and clinical guidance, it set about taking a 'whole systems' approach to managing corporate risk, giving one of its directors responsibility for the leadership of health and safety for the first time. Health and safety was also made a key item on the board agenda.

This has resulted in a much better integrated health and safety management system that increases the opportunity to identify and manage all corporate risks, and a much more open culture, improving reporting and monitoring. The board actively promotes a culture that gives staff the confidence to report incidents. This has resulted in:

- incidence rates reduced by 16% over two years;

- insurance premiums reduced by 10%.

Case study - British Sugar

British Sugar had an excellent safety record and was devastated in 2003 when it suffered three fatalities. Although health and safety had always been a business priority, the company recognised that a change in focus was needed to achieve behavioural change. This included:

- the CEO assigning health and safety responsibilities to all directors, and monthly reports go to the board;

- creating effective working partnerships with employees, trade unions and others;

- overseeing a behavioural change programme and audits;

- publishing annual health and safety targets, and devising initiatives to meet them.

Results include:

A two thirds reduction in both lost time and minor injury frequency rates over a 10 year period.

much greater understanding by directors of health and safety risks.

Case study – Mid and West Wales Fire and Rescue Service

To give health and safety a high priority, Mid and West Wales Fire and Rescue Service recognised that it was critical for its leadership to demonstrate to its staff that accountability for health and safety was a fundamental element in the success of its overall service delivery. The director of service policy and planning was nominated as the health and safety director for the service in order to clearly define the importance this subject held within the organisation. The director implemented a revised health and safety framework, which included a programme of fire station visits to engage the workforce, and placed a renewed emphasis on improving incident reporting, investigation and monitoring procedures. The service has reported:

- £100,000 reduction in insurance liability premiums in one year through improved corporate strategic risk management;

- 50% reduction in sickness absence through work related injury over a two year period;

- 50% reduction in injury incidence rate over a three year period.

Case study – Sainsbury's

An external health and safety audit identified a need to develop a unified approach, and also recommended more direction from the board, to develop an effective strategy.

The result was a radical revision of the company's approach, including:

- the group human resources director creating a health and safety vision, supported by a plan with targets over three years;

- training on health and safety responsibilities was introduced for all board directors.

This has resulted in:

- the board providing a role model for health and safety behaviour;

- 17% reduction in sickness absence;

- 28% reduction in reportable incidents;

- improved morale and pride in working for the company;

- raising the profile of health and safety so it is becoming embedded in the culture of the organisation.

When leadership falls short

Many high-profile safety cases over the years have been rooted in failures of leadership. When board members do not lead effectively on health and safety management, the consequences can be severe. These examples mark issues for all boards to consider.

Competent advice, training and supervision

Following the fatal injury of an employee maintaining machinery at a recycling firm employing approximately 30 people, a company director received a 12-month custodial sentence for manslaughter. The machinery was not properly isolated and started up unexpectedly.

An HSE and police investigation revealed there was no safe system of work for maintenance; instruction, training and supervision were inadequate. HSE's investigating principal inspector said: 'Evidence showed that the director chose not to follow the advice of his health and safety adviser and instead adopted a complacent attitude, allowing the standards in his business to fall.'

The managing director of a manufacturing company with around 100 workers was sentenced to 12 months' imprisonment for manslaughter following the death of an employee who became caught in unguarded machinery. The investigation revealed that, had the company adequately maintained guarding around a conveyor, the death would have been avoided.

The judge made clear that whether the managing director was aware of the situation was not the issue: he should have known as this was a long-standing problem. An area manager also received a custodial sentence. The company received a substantial fine and had to pay the prosecution's costs.

Risk assessment

A company and its officers were fined a total of £245,000 and ordered to pay costs of £75,500 at Crown Court in relation to the removal of asbestos. The company employed ten, mostly young, temporary workers; they were not trained or equipped to safely remove the asbestos, nor warned of its risk. The directors were also disqualified from holding any company directorship for two years and one year respectively.

Is this page useful?

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 18 November 2019

A review and critique of academic lab safety research

- A. Dana Ménard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3503-5559 1 &

- John F. Trant ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4780-4968 2

Nature Chemistry volume 12 , pages 17–25 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

41k Accesses

117 Citations

221 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Chemical education

- Chemical safety

- Scientific community

- Social sciences

Over the past ten years, there have been several high-profile accidents in academic laboratories around the world, resulting in significant injuries and fatalities. The aftermath of these incidents is often characterized by calls for reflection and re-examination of the academic discipline’s approach to safety research and policy. However, the study of academic lab safety is still underdeveloped and necessary data about changes in safety attitudes and behaviours has not been gathered. This Review article critically examines the state of academic chemical safety research from a multifactorial stance, including research on the occurrence of lab accidents, contributors to lab accidents, the state of safety training research and the cultural barriers to conducting safety research and implementing safer lab practices. The Review concludes by delineating research questions that must be addressed to minimize future serious academic laboratory incidents as well as stressing the need for committed leadership from our research institutions.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Testing the effectiveness of interactive training on sexual harassment and assault in field science

Inappropriate behaviours in a dental training environment: pilot of a UK-wide questionnaire

Biomedical doctoral students’ research practices when facing dilemmas: two vignette-based randomized control trials

Baudendistel, B. Investigation Report University of California, Los Angeles , Case No. S1110-003-09 (Department of Industrial Relations, Division of Occupational Safety and Health, Los Angeles, 2009).

Technical Bulletin AL-134: Handling air-sensitive reagents (Sigma Aldrich, 2012).

Benderley, B. L. California investigation report explains what went wrong for Sangji. Science http://blogs.sciencemag.org/sciencecareers/2012/01/yesterday-we-pu.html (2012).

Allen, K. A young lab worker, a professor and a deadly accident. Toronto Star (2014); https://www.thestar.com/news/world/2014/03/30/a_young_lab_worker_a_professor_and_a_deadly_accident.html

Benderly, B. L. Danger in school labs. Sci. Am. 303 , 18–20 (2010).

PubMed Google Scholar

Grabowski, L. E. & Goode, S. R. Review and analysis of safety policies of chemical journals. J. Chem. Health Saf. 23 , 30–35 (2016).

Google Scholar

Langerman, N. Warning to all principal investigators. J. Chem. Health Saf. 19 , 42–43 (2012).

Kemsley, J. N. University of Hawaii fined $115,500 for lab explosion. Chem. Eng. News (2016); http://cen.acs.org/articles/94/web/2016/09/University-Hawaii-fined-115500-lab.html

Pinghui, Z. Three students die in blast at Beijing university laboratory. South China Morning Post (2018); http://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/2179543/three-students-die-blast-beijing-university-laboratory

Van Noorden, R. A death in the lab. Nature 472 , 270–271 (2011).

Texas Tech University laboratory explosion (U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, 2010).

Kemsley, J. N. 10 years after Sheri Sangji’s death, are academic labs any safer? Chem. Eng. News (2018).

Hunter, K. et al. Guidelines for chemical laboratory safety in academic institution s (American Chemical Society, 2016); https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/about/governance/committees/chemicalsafety/publications/acs-safety-guidelines-academic.pdf

Kaufman, J. A. Killed in lab accidents: Memorial Wall. Lab Safety https://www.labsafety.org/memorial-wall (2019).

Miller, A. J. M. & Tonks, I. A. Let’s talk about safety: Open communication for safer laboratories. Organometallics 37 , 3225–3227 (2018).

CAS Google Scholar

Young, J. A. How “safe” are the students in my lab? Do teachers really care. J. Chem. Educ. 60 , 1067–1068 (1983).

Accidents in waiting. Nature 472 , 259 (2011).

Jorgensen, E. F. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Research Laboratory Safe Behavior Survey (RLSBS). J. Chem. Health Saf. 24 , 38–43 (2017).

Peplow, M. & Marris, E. How dangerous is chemistry? Nature 441 , 560–561 (2006).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hellman, M. A., Savage, E. P. & Keefe, T. J. Epidemiology of accidents in academic chemistry laboratories. Part 1. Accident data survey. J. Chem. Educ. 63 , A267 (1986).

Van Noorden, R. Safety survey reveals lab risks. Nature 493 , 9–10 (2013).

Ayi, H.-R. & Hon, C.-Y. Safety culture and safety compliance in academic laboratories: A Canadian perspective. J. Chem. Health Saf. 25 , 6–12 (2018).

Simmons, H. E., Matos, B. & Simpson, S. A. Analysis of injury data to improve safety and training. J. Chem. Health Saf. 24 , 21–28 (2017).

Sieloff, A. C., Shendell, D. G., Marshall, E. G. & Ohman-Strickland, P. An examination of injuries and respiratory irritation symptoms among a sample of undergraduate chemistry students from a Public Northeastern University. J. Chem. Health Saf. 20 , 17–26 (2013).

Probst, T. M., Barbaranelli, C. & Petitta, L. The relationship between job insecurity and accident under-reporting: A test in two countries. Work Stress 27 , 383–402 (2013).

Rathman, T. L. & Schwindeman, J. A. Preparation, properties, and safe handling of commercial organolithiums: Alkyllithiums, lithium sec-organoamides, and lithium alkoxides. Org. Process Res. Dev. 18 , 1192–1210 (2014).

Mikula, H. et al. Practical and efficient large-scale preparation of dimethyldioxirane. Org. Process Res. Dev. 17 , 313–316 (2013).

Morandi, B. & Carreira, E. M. Iron-catalyzed cyclopropanation in 6 M KOH with in situ generation of diazomethane. Science 335 , 1471–1474 (2012).

Busura, S., Khan, F., Hawboldt, K. & Iliyas, A. Quantitative risk-based ranking of chemicals considering hazardous thermal reactions. J. Chem. Health Saf. 21 , 27–38 (2014).

Frontier, A. Laboratory techniques and methods to improve your experimental skills. Not Voodoo http://chem.chem.rochester.edu/~nvd/index.php (2019).

Lowe, D. How not to do it: Tertiary butyllithium. Science Mag https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2007/03/01/how_not_to_do_it_tertiary_butyllithium (2007).

Snyder, S. A. Essential Reagents for Organic Synthesis (eds Fuchs, P., Bode, J., Charette, A. & Rovis, T) (Wiley, 2019).

Urben, P. G. Bretherick’s Handbook of Reactive Chemical Hazards 7th edn (Elsevier, 2017).

Bertozzi, C. R. Ingredients for a positive safety culture. ACS Cent. Sci. 2 , 764–766 (2016).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Huising, R. & Silbey, S. S. Constructing consequences for noncompliance: The case of academic laboratories. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 649 , 157–177 (2013).

Hendershot, D. C. Process safety: Is safety “common sense”? J. Chem. Health Saf. 19 , 35–36 (2012).

Kemsley, J. N. Learning from UCLA. Chem. Eng. News 87 , 29–34 (2009).

Schmidt, H. Anatomy of an incident—Multiple failure of safety systems under stress. J. Chem. Health Saf. 25 , 6–11 (2018).

Cournoyer, M. E., Trujillo, S., Lawton, C. M., Land, W. M. & Schreiber, S. B. Anatomy of an incident. J. Chem. Health Saf. 23 , 40–48 (2016).

Phifer, R. Case study – Incident investigation: Laboratory explosion. J. Chem. Health Saf. 21 , 2–5 (2014).

Reason, J. The contribution of latent human failures to the breakdown of complex systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B 327 , 475–484 (1990).

Young, J. A. How complacency can jeopardize safety. Chem. Health Saf. 6 , 5 (1999).

Wu, T.-C., Liu, C.-W. & Lu, M.-C. Safety climate in university and college laboratories: Impact of organizational and individual factors. J. Saf. Res. 38 , 91–102 (2007).

Steward, J. E., Wilson, V. L. & Wang, W.-H. Evaluation of safety climate at a major public university. J. Chem. Health Saf. 23 , 4–12 (2016).

Schröder, I., Huang, D. Y. Q., Ellis, O., Gibson, J. H. & Wayne, N. L. Laboratory safety attitudes and practices: A comparison of academic, government, and industry researchers. J. Chem. Health Saf. 23 , 12–23 (2016).

McEwen, L., Stuart, R., Sweet, E. & Izzo, R. Baseline survey of academic chemical safety information practices. J. Chem. Health Saf. 25 , 6–10 (2018).

King, M. F. & Bruner, G. C. Social desirability bias: A neglected aspect of validity testing. Psychol. Market. 17 , 79–103 (2000).

Edwards, A. L. The social desirability variable in personality assessment and research. (Dryden Press, 1957).

Wardlaw, M. J. Three lessons for a better cycling future. BMJ 321 , 1582–1585 (2000).

Finkelstein, E. A., Strombotne, K. L., Chan, N. L. & Krieger, J. Mandatory menu labeling in one fast-food chain in King County, Washington. Am. J. Prev. Med. 40 , 122–127 (2011).

Ménard, A. D., Houser, C., Brander, R. W., Trimble, S. & Scaman, A. The psychology of beach users: Importance of confirmation bias, action, and intention to improving rip current safety. Nat. Hazards 94 , 953–973 (2018).

Bretherick, L. Chemical laboratory safety: The academic anomaly. J. Chem. Educ. 67 , A12 (1990).

Hill, R. H. Make safety a habit! J. Chem. Health Saf. 25 , 12–17 (2018).

Darley, J. M. & Latane, B. Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 8 , 377–383 (1968).

Leggett, D. J. Identifying hazards in the chemical research laboratory. Process Saf. Prog. 31 , 393–397 (2012).

Stuart, R. Emergency response training for laboratory workers. J. Chem. Health Saf. 17 , 29–32 (2010).

Mogielnicki, R. P., Stevenson, K. A. & Willemain, T. R. Patient and bystander response to medical emergencies. Med Care 13 , 753–762 (1975).

Shotland, R. L. & Heinold, W. D. Bystander response to arterial bleeding: Helping skills, the decision-making process, and differentiating the helping response. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 49 , 347–356 (1985).

Hill, R. H. & Finster, D. C. Academic leaders create strong safety cultures in colleges and universities. J. Chem. Health Saf. 20 , 27–34 (2013).

West, S. S., Westerlund, J. F., Stephenson, A. L., Nelson, N. C. & Nyland, C. K. Safety in science classrooms: What research and best practice say. Educ. For. 67 , 174–183 (2003).

Withers, J. H., Freeman, S. A. & Kim, E. Learning and retention of chemical safety training information: A comparison of classroom versus computer-based formats on a college campus. J. Chem. Health Saf. 19 , 47–55 (2012).

Nelson, D. A. Incorporating chemical health and safety topics into chemistry curricula: Past accomplishments and future needs. Chem. Health Saf. 6 , 43–48 (1999).

Fivizzani, K. P. Where are we with lab safety education: Who, what, when, where, and how? J. Chem. Health Saf. 23 , 18–20 (2016).

Wood-Black, F. Incorporating safety into the general chemistry curriculum. J. Chem. Health Saf. 21 , 14–21 (2014).

Crockett, J. M. Laboratory safety for undergraduates. J. Chem. Health Saf. 18 , 16–25 (2011).

Bradley, S. Integrating safety into the undergraduate chemistry curriculum. J. Chem. Health Saf. 18 , 4–10 (2011).

Burchett, S., Pfaff, A., Hayes, J. & Woelk, K. Exploding misconceptions: Developing a culture of safety through learner driven activities. J. Chem. Health Saf. 24 , 36–42 (2017).

Matson, M. L., Fitzgerald, J. P. & Lin, S. Creating customized, relevant, and engaging laboratory safety videos. J. Chem. Educ. 84 , 1727–1728 (2007).

Karapantsios, T. D., Boutskou, E. I., Touliopoulou, E. & Mavros, P. Evaluation of chemical laboratory safety based on student comprehension of chemicals labelling. Ed. Chem. Eng. 3 , e66–e73 (2008).

Reniers, G. L. L., Ponnet, K. & Kempeneers, A. Higher education chemical lab safety interventions: Efficacious or ineffective? J. Chem. Health Saf. 21 , 4–8 (2014).

Gallion, L. A., Samide, M. J. & Wilson, A. M. Demonstrating the importance of cleanliness and safety in an undergraduate teaching laboratory. J. Chem. Health Saf. 22 , 28–31 (2015).

Alaimo, P. J., Langenhan, J. M., Tanner, M. J. & Ferrenberg, S. M. Safety teams: An approach to engage students in laboratory safety. J. Chem. Educ. 87 , 856–861 (2010).

Kennedy, S. & Palmer, J. Teaching safety: 1000 students at a time. J. Chem. Health Saf. 18 , 26–31 (2011).

Makransky, G., Thisgaard, M. W. & Gadegaard, H. Virtual simulations as preparation for lab exercises: Assessing learning of key laboratory skills in microbiology and improvement of essential non-cognitive skills. PLoS ONE 11 , e0155895 (2016).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Staehle, I. O. et al. An approach to enhance the safety culture of an academic chemistry research laboratory by addressing behavioral factors. J. Chem. Educ. 93 , 217–222 (2016).

McGarry, K. A. et al. Student involvement in improving the culture of safety in academic laboratories. J. Chem. Educ. 90 , 1414–1417 (2013).

Ritch, D. & Rank, J. Laboratory safety in the biology lab. Bioscene 27 , 17–22 (2001).

Kapin, J. M. Beyond chemical safety— an integrated approach to laboratory safety management. Chem. Health Saf. 6 , 20–22 (1999).

Shariff, A. M. & Norazahar, N. At-risk behaviour analysis and improvement study in chemical engineering laboratories. Int. J. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2 , 51–55 (2011).

Wyllie, R., Lee, K., Morris-Benavides, S. & Matos, B. What to expect when you’re inspecting: A summary of academic laboratory inspection programs. J. Chem. Health Saf. 23 , 18–24 (2016).

Ferjencik, M. & Jalovy, Z. What can be learned from incidents in chemistry labs. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 23 , 630–636 (2010).

Young, J. A. The professional practice of chemical safety. Chem. Health Saf. 6 , 41–42 (1999).

Marendaz, J.-L., Friedrich, K. & Meyer, T. Safety management and risk assessment in chemical laboratories. CHIMIA 65 , 734–737 (2011).

Camino, F. E. Make safety awareness a priority: Use a login software in your research facility. J. Chem. Health Saf. 24 , 22–25 (2017).

Nitsche, C. I., Whittick, G. & Manfredi, M. Collecting reaction incident information: Engaging the community in sharing safety learnings. J. Chem. Health Saf. 25 , 2–5 (2018).

LaPierre, J. It’s 1:30 a.m.-Do you know who’s in your laboratories? Chem. Health Saf. 6 , 31–33 (1999).

Mulcahy, M. B. et al. College and university sector response to the U.S. Chemical Safety Board Texas Tech incident report and UCLA laboratory fatality. J. Chem. Health Saf. 20 , 6–13 (2013).

National Research Council. Prudent practices in the laboratory: Handling and disposal of chemicals (The National Academies Press, 1995).

Bayer, R. Lab safety as a collateral duty in small colleges. J. Chem. Educ. 61 , A259 (1984).

Kaufman, J. A. Safety in the academic laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 55 , A337 (1978).

Scherz, P. Risk, prudence and moral formation in the laboratory. J. Moral Educ. 47 , 304–315 (2018).

Ashbrook, P. Laboratory safety in academia. J. Chem. Health Saf. 20 , 62 (2013).

Ashbrook, P. C. Hazard assessment. J. Chem. Health Saf. 21 , 35 (2014).

Ashbrook, P. C. Accountability. J. Chem. Health Saf. 20 , 48 (2013).

Czornyj, E., Newcomer, D., Schroeder, I., Wayne, N. L. & Merlic, C. A. Proceedings of the 2016 Workshop Safety By Design – Improving safety in research laboratories. J. Chem. Health Saf. 25 , 36–49 (2018).

Backus, B. D. et al. Laboratory safety culture: Summary of the chemical education research and practice – Safety in chemistry education panel discussion at the 46th Midwest and 39th Great Lakes Joint Regional American Chemical Society Meeting, St. Louis, Missouri, on October 21, 2011. J. Chem. Health Saf. 19 , 20–24 (2012).

Langerman, N. Laboratory safety? J. Chem. Health Saf. 16 , 49–50 (2009).

Langerman, N. Reactive chemistry incidents in laboratories. J. Chem. Health Saf. 16 , 23–26 (2009).

McCroskey, J. C. in Teaching communication: Theory, research, and methods (eds Daly, J.A., Friedrich, G.W. & Vangelisti, A.L.) 471–479 (Erlbaum Associates, 1990).

One injured in lab explosion at UCLA. Los Angeles Daily News https://www.dailynews.com/2019/02/05/one-injured-in-lab-explosion-at-ucla/ (2019).

Download references

Acknowledgements

ADM and JFT would like to thank the University of Windsor for salary support for the preparation of this work. We would also like to thank C. Houser, K. Soucie, M. Bondy, J. Hayward and D. Cavallo-Medved for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Science, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada

A. Dana Ménard

Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada

John F. Trant

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.D.M. wrote the draft of the paper; both A.D.M. and J.F.T. conducted the literature search and analysis; both A.D.M. and J.F.T. revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to A. Dana Ménard or John F. Trant .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The investigation report prepared by California’s Division of Occupational Safety & Health relating to the laboratory accident at UCLA in 2008 that led to the death of Sheharbano Sangji.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ménard, A.D., Trant, J.F. A review and critique of academic lab safety research. Nat. Chem. 12 , 17–25 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0375-x

Download citation

Received : 18 January 2019

Accepted : 11 October 2019

Published : 18 November 2019

Issue Date : January 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-019-0375-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Laboratory safety regulations and training must emphasize the underpinning research ethics perspectives.

- Bor Luen Tang

Journal of Academic Ethics (2024)

Developing a gamified artificial intelligence educational robot to promote learning effectiveness and behavior in laboratory safety courses for undergraduate students

- Qi-Fan Yang

- Li-Wen Lian

- Jia-Hua Zhao

International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education (2023)

Insights from a laboratory fire

- Mitchell P. Jones

- Kathrin Weiland

- Alexander Bismarck

Nature Chemistry (2023)

Large language models for chemistry robotics

- Naruki Yoshikawa

- Marta Skreta

- Animesh Garg

Autonomous Robots (2023)

Rank Has Its Privileges: Explaining Why Laboratory Safety Is a Persistent Challenge

- Gokce Basbug

- Ayn Cavicchi

- Susan S. Silbey

Journal of Business Ethics (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 31 August 2020

Exploring psychological safety in healthcare teams to inform the development of interventions: combining observational, survey and interview data

- Róisín O’Donovan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1993-5319 1 &

- Eilish McAuliffe 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 20 , Article number: 810 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

28k Accesses

64 Citations

40 Altmetric

Metrics details

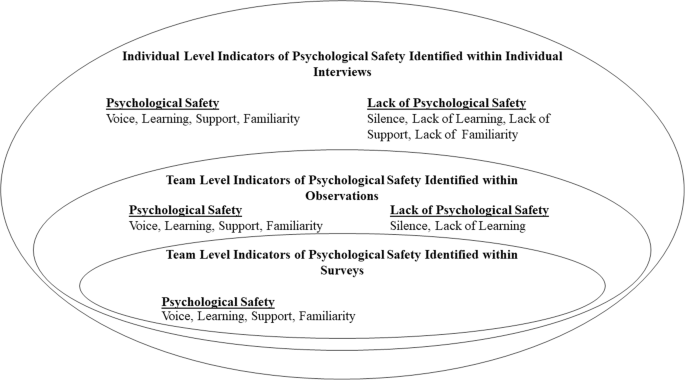

Psychological safety allows healthcare professionals to take the interpersonal risks needed to engage in effective teamwork and to maintain patient safety. In order to improve psychological safety in healthcare teams, an in-depth understanding of the complex and nuanced nature of psychological safety is needed. Psychological safety concepts, including voice, silence, learning behaviour, support and familiarity, informed the current study’s investigation of psychological safety. This study aims to use a mixed-methods approach to develop an in-depth understanding of psychological safety within healthcare teams and to build on this understanding to inform the development of future interventions to improve it.

Survey, observational and interview data are triangulated in order to develop an in- depth understanding of psychological safety within four healthcare teams, working within one case study hospital. The teams taking part included one multidisciplinary and three unidisciplinary teams. Observational and survey data were collected during and immediately following team meetings. Individual interviews were conducted with 31 individuals across the four teams. Thematic analysis was used to analyse these interviews.

Survey results indicated a high level of psychological safety. However, observations and interviews captured examples of silence and situations where participants felt less psychologically safe. Findings from across all three data sources are discussed in relation to voice and silence, learning, familiarity and support.

The results of this study provide a detailed description and in-depth understanding of psychological safety within four healthcare teams. Based on this, recommendations are made for future research and the development of interventions to improve psychological safety.

Peer Review reports

Psychological safety is a multi-dimensional, dynamic phenomenon that concerns team members’ perception of whether it is safe to take interpersonal risks at work [ 1 ]. It is particularly important within healthcare teams who need to work interdependently to co-ordinate safe patient care within a highly complex, dynamic and high stakes work environment [ 2 ]. However, a culture of fear and low psychological safety still exists within healthcare organisations [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. There is a need to develop and implement interventions to improve psychological safety within these teams [ 8 ]. The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of psychological safety within healthcare teams. Cultivating psychological safety is necessary in order to enable healthcare teams to collectively redesign processes and services to cope with new challenges, learn from mistakes and implement changes accordingly [ 9 ]. In order to improve psychological safety, we must first understand the complexity and nuance of psychological safety within healthcare teams [ 8 , 10 ].

To date, there has been a paucity of cross-level and multilevel research on psychological safety [ 10 ]. This has limited our understanding of psychological safety, the concepts related to it and whether it varies across teams within the same organisation [ 10 ]. Within organisational research, collecting different kinds of data on the same phenomenon and triangulating this data can help researchers assess complex phenomena, such as psychological safety, more accurately [ 8 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. In the current study we use survey, observational and interview data to develop an in-depth understanding of psychological safety within healthcare teams. Building on this understanding, we aim to inform the development of an intervention to improve psychological safety.

The constructs which informed our study design our outlined below. These include constructs which have been linked to either low or high psychological safety (voice and learning behaviour) and which have been found to support psychological safety (positive interpersonal relationships). These constructs play a particularly important role within the context of healthcare teams.

Psychological safety promotes voice and learning behaviour. Speaking up and voice behaviour are interpersonally risky behaviours which play an important role in healthcare teams [ 8 ]. Feeling psychologically safe can enable team members to engage in speaking up behaviour, such as asking questions, pointing out a mistake or near miss and making suggestions for improvement [ 2 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. Psychological safety also enables learning behaviours, such as seeking help or feedback [ 1 , 17 , 18 ]. Learning behaviours are integral to healthcare teams’ ability to manage demanding conditions, with rapidly evolving knowledge and practice as well as their ability to learn from failure [ 17 , 18 ]. When healthcare professionals prioritise patient safety by engaging in speaking up and learning behaviours, it is indicative of their levels of psychological safety [ 19 ].

On the other hand, lack of psychological safety inhibits team members from speaking up and causes them to opt for avoidance behaviours, such as silence [ 20 ]. It is important to acknowledge that although employees may frequently engage in voice behaviour, they could also be withholding other ideas, suggestions or concerns [ 20 ]. This highlights the need to go beyond observable behaviours to explore the nuance and complexities of individuals’ experience of psychological safety. In order to do so, this study uses a combination of survey, observation and interview data to gain a full understanding of psychological safety.

Positive interpersonal relationships drive psychological safety [ 21 , 22 ]. Within healthcare teams, having positive relationships, effective role models and better teamwork climates encourages healthcare professionals to speak up for safety [ 19 ]. Team members relationship with the team leader has been found to influence their sense of psychological safety. For example, when leaders engage in supportive behaviour, such as inclusiveness and openness, they foster psychological safety for other team members [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. Peer support and trust among team members also improves psychological safety within teams [ 10 ]. Psychological safety can build across time, increasing as team members become more familiar with one another and have positive experiences of engaging in interpersonally risky behaviour [ 10 , 13 , 26 , 27 ]. While positive, supportive and trusting interpersonal relationships can foster psychological safety, it is important to note that psychological safety does not imply a team without any conflict or problems [ 5 ]. Psychological safety is needed in order for productive conflict, such as task conflict, to occur [ 28 ]. Task conflict concerns disagreements related to differences in viewpoints, ideas and opinions about the task being performed and can result in learning and improved performance [ 13 , 28 , 29 ].

In this study, focusing on a single hospital as a case study, we use a mixed methods approach to further our understanding of psychological safety within four healthcare teams. We combine data collected through surveys, observations and individual interviews to gain a holistic understanding of psychological safety in these teams. Building on this understanding, we aim to inform the development of future interventions to improve psychological safety in healthcare teams.

Research setting and participants

This study was undertaken by the authors as part of a wider body of research aiming to develop an intervention to improve psychological safety in healthcare teams. This research was conducted with healthcare professionals working on one of four healthcare teams from within the same acute, suburban hospital. Three of the teams were unidisciplinary – physiotherapists, nurses and speech and language therapists – and one was multidisciplinary. The authors collaborated closely with hospital management in order to recruit healthcare teams from within the hospital. These teams were selected in collaboration with hospital management using purposive sampling in order to identify different team types as well as teams that held meetings amenable to observation. The lead researcher contacted the leader of each team to ask if their team would be interested in taking part in the team observation and survey. Before beginning observations, team members from within each team were asked to consent to the meeting being observed and to completing the survey following the meeting. For interviews, a combination of purposive sampling and snowball sampling were employed to recruit team members from within each team. After the observation and surveys were complete, the researcher informed the team that anyone who was willing to take part in an interview could contact them (the researcher) or their team leader who would then refer them to the lead researcher. Team members were recruited from across all staff grades and included team leaders as well as senior and junior team members [ 30 ]. The total number of participants who took part in each phase of data collection can be found in Table 1 .

The team as a whole were observed during regularly scheduled team meetings. Of those who attended the meeting, there was 100% participation rate in the survey within teams A and B. There was one team members in team C and another in team D who was part of the observations but did not complete a survey. Since surveys were kept completely anonymous, it was not possible to assess whether the same participants who completed the survey also took part in an interview. In teams A ( n = 2), B ( n = 1) and D ( n = 1), participants who were not present during observations and who did not complete a survey were recruited by the team leader to take part in an interview.

Data collection

Within case study designs, the use of multiple sources of evidence in recommended in order to capture a holistic understanding of the phenomena being studied [ 31 ]. The current study triangulates multiple sources of data in order to gain an in-depth understanding of psychological safety in healthcare teams. Rather than adopting the commonly used approach to triangulation to gain more credible or valid results, we draw on a post-modern paradigm which views reality as having multiple, fractured dimensions and being socially constructed. This approach requires acknowledgment that all research findings are shaped by the approach used to collect them and that different methods of data collection will offer different results [ 32 ]. Therefore, we use multiple methods to deepen our understanding of psychological safety by encouraging re-interpretation of findings as data sources reveal new insights and, thus, facilitating a more complex and in-depth exploration of healthcare professionals experiences of psychological safety. This approach to triangulation of data has been termed crystallization [ 33 ].

Composite measure of psychological safety

Survey and observational data were collected using the composite measure developed and presented in a recent paper focused on measuring psychological safety in healthcare teams [ 34 ]. For each team, one weekly meeting was observed using the observation measure, which captured voice, silence, supportive or unsupportive and familiarity behaviours. The observational data were collected as part of a pilot test of the measure and, as a result, behaviours were amended following each observation, however the overall categories remained the same. Observations were completed by one researcher who sat at the table or in the room where each meeting was conducted. The observer tracked the behaviours displayed by the team leader and team members by making a mark in the “behaviour count” box for the relevant behaviour. Observations were made by only one researcher in order to reduce the inhibiting effect the presence of two researchers might have on the team’s behaviour. The observed team meetings varied in length. The meeting held by Team A lasted 30 min, Team B’s meeting lasted 90 min, Team C’s meeting lasted 70 min and Team D had a meeting which lasted 120 min. All meeting were the teams regularly scheduled team meetings. Each discussed clinical and/or management issues that were relevant to their team.

Following the meeting, team members were asked to complete the survey component of the composite measure. There were three sections in the survey which assessed participants’ psychological safety in relation to: the team leader, other team members and the team as a whole. As part of a pilot test of the survey, a 7 point Likert scale was used for teams A-C. For team D, a 10 point Likert scale was tested. This was done in order to check if using a 10 point Likert scale would give participants an even wider spectrum of response options and, thus, allow the survey to capture more variability in participants’ responses [ 35 ]. Surveys did not ask for any identifiable information and were kept completely anonymous. Participants completed their survey in the same room as one another. There was plenty of space for them to move freely in order to complete their survey in private and surveys were handed directly to the researcher once completed.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 31 participants from across the four teams. The full interview schedule is presented as a supplementary file . This interview data was collected in order to gain an in-depth understanding of individuals’ experience of psychological safety and explore whether there were any emerging differences compared to the team level observations or survey responses. Interviews were conducted in a private room located within the case study hospital and lasted an average of 28 min. A full description of the process used to collect and analyse the interview data can be found in O'Donovan, De Brún & McAuliffe (in preparation). Hybrid inductive-deductive thematic analysis was used to identify themes which correspond to the concepts covered in the observations and survey data. Descriptive, open codes were assigned to each interview. These codes were then reviewed and refined, with reference to the psychological safety literature, in order to identify overarching themes. Analysis also compared findings from individuals in the same team to explore the consistencies and inconsistencies across cases. Thematic analysis was chosen because it is a theoretically flexible approach to qualitative analysis which allows the combination of inductive and deductive methods [ 36 , 37 ]. As highlighted by Braun and Clarke [ 36 ], thematic analysis is a useful method for working within a participatory research paradigm, with participants as collaborators, and for producing qualitative analysis which can inform policy development. Since the overarching aim of this study was to inform the development of an intervention to improve psychological safety which is grounded in the experiences of healthcare professionals, thematic analysis was particularly suitable. Our analysis focused on themes which captured participants’ experiences of speaking up or remaining silent, engaging in learning behaviour and their experience of support, or lack of support and familiarity within the team.

Ethical approval was obtained for this study from the Human Research Ethics Committee in University College Dublin (Reference number: LS-17-67). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to each stage of data collection. In order to maintain anonymity, no identifiable information was collected during observations or surveys. Interviews were assigned a code made up of P (participant), interview number (e.g. the first interview conducted within each team was given the number 1) and team letter (A, B, C or D) and any identifiable characteristics were removed from the interview transcripts.

Survey results

All survey responses are displayed in Table 2 . They indicated that team members felt psychologically safe. In team A, a mean response of 6.700 was given for section 1, 6.597 for section 2 and 6.212 for section 3.

Observations

A positive, constructive atmosphere was observed during the team meeting. While the team leader spoke the most, team members were given opportunities to speak up. However, five to six team members dominated the discussion and not all team members spoke. These observations indicated that both team members and team leaders engaged in voice, learning, supportive and familiarity behaviours. There were no counts of defensive voice, silence or unsupportive behaviour. The specific behaviours displayed can be seen in Table 3 and observer ratings can be seen in Table 4 .

Voice and silence

Team members described an open team atmosphere where they felt listened to, respected and psychologically safe. They felt comfortable speaking up about work issues or things “they felt very strongly” about and would go to their team leader if they were “frustrated” or “struggling” . Interviews highlighted that there were opportunities to speak up during meetings. However, team members remained silent about certain issues. Some team members believed that discussing conflict, personal or confidential issues within a team setting may not be “appropriate” . They would discuss these issues outside the team setting instead.

“but I would say maybe it’s when the group disassembles that some of those opinions come out, you know, it mightn’t always be that effective.”