How to Write History that People Want to Read- © 2011

- Ann Curthoys 0 ,

- Ann McGrath 1

University of Sydney, AustraliaYou can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar Australian National University, Australia7760 Accesses 3 Citations 18 Altmetric This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access. Access this book- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout Other ways to accessLicence this eBook for your library Institutional subscriptions About this bookSimilar content being viewed by others.  Introduction Historiography, Renaissance - 21st century

- history of literature

Table of contents (13 chapters)Front matter. - Ann Curthoys, Ann McGrath

Which history to tell?Who is your history for, crying in the archives, history in 3d, how to avoid writer’s block, once upon a time, narrative, plot, action, styling pasts for presents, character and emotion, footnote fetishism, back matter. 'A really excellent book. It is written in a bright, informal style with some hard-and-fast rules balanced with advice, warning and very positive encouragement.' Alan Atkinson, author of The Europeans in Australia 'This witty little volume reveals the tricks and tips of the profession and recounts endearing anecdotes about the authors' own experiences as historians. A delightful read, this is also a seriously good advice manual. Refreshing, sensitive, thorough, here are two wise women who practise what they preach.' Philippa Levine, author of The British Empire: Sunrise to Sunset 'Historians of all kinds, whether scholars, students or commercial authors, all share a wish to maximise their publics: this lively and practical primer will tell them how. Lucid, unpretentious and punchy, it is crammed with sage advice, shrewd criticism and dozens of samples of compelling history writing.' Iain McCalman, author of Darwin's Armada Authors and AffiliationsAnn Curthoys Ann McGrath About the authorsBibliographic information. Book Title : How to Write History that People Want to Read Authors : Ann Curthoys, Ann McGrath DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-230-30496-3 Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan London eBook Packages : Palgrave History Collection , History (R0) Copyright Information : Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Nature America Inc. 2011 Softcover ISBN : 978-0-230-29038-9 Published: 17 June 2011 eBook ISBN : 978-0-230-30496-3 Published: 30 April 2016 Edition Number : 1 Number of Pages : VIII, 265 Topics : Historiography and Method , Creative Writing , Science, Humanities and Social Sciences, multidisciplinary Policies and ethics - Find a journal

- Track your research

Thesis StatementsWhat is a thesis statement. Your thesis statement is one of the most important parts of your paper. It expresses your main argument succinctly and explains why your argument is historically significant. Think of your thesis as a promise you make to your reader about what your paper will argue. Then, spend the rest of your paper–each body paragraph–fulfilling that promise. Your thesis should be between one and three sentences long and is placed at the end of your introduction. Just because the thesis comes towards the beginning of your paper does not mean you can write it first and then forget about it. View your thesis as a work in progress while you write your paper. Once you are satisfied with the overall argument your paper makes, go back to your thesis and see if it captures what you have argued. If it does not, then revise it. Crafting a good thesis is one of the most challenging parts of the writing process, so do not expect to perfect it on the first few tries. Successful writers revise their thesis statements again and again. A successful thesis statement: - makes an historical argument

- takes a position that requires defending

- is historically specific

- is focused and precise

- answers the question, “so what?”

How to write a thesis statement: Suppose you are taking an early American history class and your professor has distributed the following essay prompt: “Historians have debated the American Revolution’s effect on women. Some argue that the Revolution had a positive effect because it increased women’s authority in the family. Others argue that it had a negative effect because it excluded women from politics. Still others argue that the Revolution changed very little for women, as they remained ensconced in the home. Write a paper in which you pose your own answer to the question of whether the American Revolution had a positive, negative, or limited effect on women.” Using this prompt, we will look at both weak and strong thesis statements to see how successful thesis statements work. While this thesis does take a position, it is problematic because it simply restates the prompt. It needs to be more specific about how the Revolution had a limited effect on women and why it mattered that women remained in the home. Revised Thesis: The Revolution wrought little political change in the lives of women because they did not gain the right to vote or run for office. Instead, women remained firmly in the home, just as they had before the war, making their day-to-day lives look much the same. This revision is an improvement over the first attempt because it states what standards the writer is using to measure change (the right to vote and run for office) and it shows why women remaining in the home serves as evidence of limited change (because their day-to-day lives looked the same before and after the war). However, it still relies too heavily on the information given in the prompt, simply saying that women remained in the home. It needs to make an argument about some element of the war’s limited effect on women. This thesis requires further revision. Strong Thesis: While the Revolution presented women unprecedented opportunities to participate in protest movements and manage their family’s farms and businesses, it ultimately did not offer lasting political change, excluding women from the right to vote and serve in office. Few would argue with the idea that war brings upheaval. Your thesis needs to be debatable: it needs to make a claim against which someone could argue. Your job throughout the paper is to provide evidence in support of your own case. Here is a revised version: Strong Thesis: The Revolution caused particular upheaval in the lives of women. With men away at war, women took on full responsibility for running households, farms, and businesses. As a result of their increased involvement during the war, many women were reluctant to give up their new-found responsibilities after the fighting ended. Sexism is a vague word that can mean different things in different times and places. In order to answer the question and make a compelling argument, this thesis needs to explain exactly what attitudes toward women were in early America, and how those attitudes negatively affected women in the Revolutionary period. Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a negative impact on women because of the belief that women lacked the rational faculties of men. In a nation that was to be guided by reasonable republican citizens, women were imagined to have no place in politics and were thus firmly relegated to the home. This thesis addresses too large of a topic for an undergraduate paper. The terms “social,” “political,” and “economic” are too broad and vague for the writer to analyze them thoroughly in a limited number of pages. The thesis might focus on one of those concepts, or it might narrow the emphasis to some specific features of social, political, and economic change. Strong Thesis: The Revolution paved the way for important political changes for women. As “Republican Mothers,” women contributed to the polity by raising future citizens and nurturing virtuous husbands. Consequently, women played a far more important role in the new nation’s politics than they had under British rule. This thesis is off to a strong start, but it needs to go one step further by telling the reader why changes in these three areas mattered. How did the lives of women improve because of developments in education, law, and economics? What were women able to do with these advantages? Obviously the rest of the paper will answer these questions, but the thesis statement needs to give some indication of why these particular changes mattered. Strong Thesis: The Revolution had a positive impact on women because it ushered in improvements in female education, legal standing, and economic opportunity. Progress in these three areas gave women the tools they needed to carve out lives beyond the home, laying the foundation for the cohesive feminist movement that would emerge in the mid-nineteenth century. Thesis ChecklistWhen revising your thesis, check it against the following guidelines: - Does my thesis make an historical argument?

- Does my thesis take a position that requires defending?

- Is my thesis historically specific?

- Is my thesis focused and precise?

- Does my thesis answer the question, “so what?”

Download as PDF  6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601 Other Resources- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

A Step-by-Step Guide to Doing Historical Research [without getting hysterical!] In addition to being a scholarly investigation, research is a social activity intended to create new knowledge. Historical research is your informed response to the questions that you ask while examining the record of human experience. These questions may concern such elements as looking at an event or topic, examining events that lead to the event in question, social influences, key players, and other contextual information. This step-by-step guide progresses from an introduction to historical resources to information about how to identify a topic, craft a thesis and develop a research paper. Table of contents: The Range and Richness of Historical Sources Secondary Sources Primary Sources Historical Analysis What is it? Who, When, Where, What and Why: The Five "W"s Topic, Thesis, Sources Definition of Terms Choose a Topic Craft a Thesis Evaluate Thesis and Sources A Variety of Information Sources Take Efficient Notes Note Cards Thinking, Organizing, Researching Parenthetical Documentation Prepare a Works Cited Page Drafting, Revising, Rewriting, Rethinking For Further Reading: Works Cited Additional Links So you want to study history?! Tons of help and links Slatta Home Page Use the Writing and other links on the lefhand menu I. The Range and Richness of Historical Sources Back to Top Every period leaves traces, what historians call "sources" or evidence. Some are more credible or carry more weight than others; judging the differences is a vital skill developed by good historians. Sources vary in perspective, so knowing who created the information you are examining is vital. Anonymous doesn't make for a very compelling source. For example, an FBI report on the antiwar movement, prepared for U.S. President Richard Nixon, probably contained secrets that at the time were thought to have affected national security. It would not be usual, however, for a journalist's article about a campus riot, featured in a local newspaper, to leak top secret information. Which source would you read? It depends on your research topic. If you're studying how government officials portrayed student activists, you'll want to read the FBI report and many more documents from other government agencies such as the CIA and the National Security Council. If you're investigating contemporary opinion of pro-war and anti-war activists, local newspaper accounts provide a rich resource. You'd want to read a variety of newspapers to ensure you're covering a wide range of opinions (rural/urban, left/right, North/South, Soldier/Draft-dodger, etc). Historians classify sources into two major categories: primary and secondary sources. Secondary Sources Back to Top Definition: Secondary sources are created by someone who was either not present when the event occurred or removed from it in time. We use secondary sources for overview information, to familiarize ourselves with a topic, and compare that topic with other events in history. In refining a research topic, we often begin with secondary sources. This helps us identify gaps or conflicts in the existing scholarly literature that might prove promsing topics. Types: History books, encyclopedias, historical dictionaries, and academic (scholarly) articles are secondary sources. To help you determine the status of a given secondary source, see How to identify and nagivate scholarly literature . Examples: Historian Marilyn Young's (NYU) book about the Vietnam War is a secondary source. She did not participate in the war. Her study is not based on her personal experience but on the evidence she culled from a variety of sources she found in the United States and Vietnam. Primary Sources Back to Top Definition: Primary sources emanate from individuals or groups who participated in or witnessed an event and recorded that event during or immediately after the event. They include speeches, memoirs, diaries, letters, telegrams, emails, proclamations, government documents, and much more. Examples: A student activist during the war writing about protest activities has created a memoir. This would be a primary source because the information is based on her own involvement in the events she describes. Similarly, an antiwar speech is a primary source. So is the arrest record of student protesters. A newspaper editorial or article, reporting on a student demonstration is also a primary source. II. Historical Analysis What is it? Back to Top No matter what you read, whether it's a primary source or a secondary source, you want to know who authored the source (a trusted scholar? A controversial historian? A propagandist? A famous person? An ordinary individual?). "Author" refers to anyone who created information in any medium (film, sound, or text). You also need to know when it was written and the kind of audience the author intend to reach. You should also consider what you bring to the evidence that you examine. Are you inductively following a path of evidence, developing your interpretation based on the sources? Do you have an ax to grind? Did you begin your research deductively, with your mind made up before even seeing the evidence. Historians need to avoid the latter and emulate the former. To read more about the distinction, examine the difference between Intellectual Inquirers and Partisan Ideologues . In the study of history, perspective is everything. A letter written by a twenty- year old Vietnam War protestor will differ greatly from a letter written by a scholar of protest movements. Although the sentiment might be the same, the perspective and influences of these two authors will be worlds apart. Practicing the " 5 Ws " will avoid the confusion of the authority trap. Who, When, Where, What and Why: The Five "W"s Back to Top Historians accumulate evidence (information, including facts, stories, interpretations, opinions, statements, reports, etc.) from a variety of sources (primary and secondary). They must also verify that certain key pieces of information are corroborated by a number of people and sources ("the predonderance of evidence"). The historian poses the " 5 Ws " to every piece of information he examines: Who is the historical actor? When did the event take place? Where did it occur? What did it entail and why did it happen the way it did? The " 5 Ws " can also be used to evaluate a primary source. Who authored the work? When was it created? Where was it created, published, and disseminated? Why was it written (the intended audience), and what is the document about (what points is the author making)? If you know the answers to these five questions, you can analyze any document, and any primary source. The historian doesn't look for the truth, since this presumes there is only one true story. The historian tries to understand a number of competing viewpoints to form his or her own interpretation-- what constitutes the best explanation of what happened and why. By using as wide a range of primary source documents and secondary sources as possible, you will add depth and richness to your historical analysis. The more exposure you, the researcher, have to a number of different sources and differing view points, the more you have a balanced and complete view about a topic in history. This view will spark more questions and ultimately lead you into the quest to unravel more clues about your topic. You are ready to start assembling information for your research paper. III. Topic, Thesis, Sources Definition of Terms Back to Top Because your purpose is to create new knowledge while recognizing those scholars whose existing work has helped you in this pursuit, you are honor bound never to commit the following academic sins: Plagiarism: Literally "kidnapping," involving the use of someone else's words as if they were your own (Gibaldi 6). To avoid plagiarism you must document direct quotations, paraphrases, and original ideas not your own. Recycling: Rehashing material you already know thoroughly or, without your professor's permission, submitting a paper that you have completed for another course. Premature cognitive commitment: Academic jargon for deciding on a thesis too soon and then seeking information to serve that thesis rather than embarking on a genuine search for new knowledge. Choose a Topic Back to Top "Do not hunt for subjects, let them choose you, not you them." --Samuel Butler Choosing a topic is the first step in the pursuit of a thesis. Below is a logical progression from topic to thesis: Close reading of the primary text, aided by secondary sources Growing awareness of interesting qualities within the primary text Choosing a topic for research Asking productive questions that help explore and evaluate a topic Creating a research hypothesis Revising and refining a hypothesis to form a working thesis First, and most important, identify what qualities in the primary or secondary source pique your imagination and curiosity and send you on a search for answers. Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive levels provides a description of productive questions asked by critical thinkers. While the lower levels (knowledge, comprehension) are necessary to a good history essay, aspire to the upper three levels (analysis, synthesis, evaluation). Skimming reference works such as encyclopedias, books, critical essays and periodical articles can help you choose a topic that evolves into a hypothesis, which in turn may lead to a thesis. One approach to skimming involves reading the first paragraph of a secondary source to locate and evaluate the author's thesis. Then for a general idea of the work's organization and major ideas read the first and last sentence of each paragraph. Read the conclusion carefully, as it usually presents a summary (Barnet and Bedau 19). Craft a Thesis Back to Top Very often a chosen topic is too broad for focused research. You must revise it until you have a working hypothesis, that is, a statement of an idea or an approach with respect to the source that could form the basis for your thesis. Remember to not commit too soon to any one hypothesis. Use it as a divining rod or a first step that will take you to new information that may inspire you to revise your hypothesis. Be flexible. Give yourself time to explore possibilities. The hypothesis you create will mature and shift as you write and rewrite your paper. New questions will send you back to old and on to new material. Remember, this is the nature of research--it is more a spiraling or iterative activity than a linear one. Test your working hypothesis to be sure it is: broad enough to promise a variety of resources. narrow enough for you to research in depth. original enough to interest you and your readers. worthwhile enough to offer information and insights of substance "do-able"--sources are available to complete the research. Now it is time to craft your thesis, your revised and refined hypothesis. A thesis is a declarative sentence that: focuses on one well-defined idea makes an arguable assertion; it is capable of being supported prepares your readers for the body of your paper and foreshadows the conclusion. Evaluate Thesis and Sources Back to Top Like your hypothesis, your thesis is not carved in stone. You are in charge. If necessary, revise it during the research process. As you research, continue to evaluate both your thesis for practicality, originality, and promise as a search tool, and secondary sources for relevance and scholarliness. The following are questions to ask during the research process: Are there many journal articles and entire books devoted to the thesis, suggesting that the subject has been covered so thoroughly that there may be nothing new to say? Does the thesis lead to stimulating, new insights? Are appropriate sources available? Is there a variety of sources available so that the bibliography or works cited page will reflect different kinds of sources? Which sources are too broad for my thesis? Which resources are too narrow? Who is the author of the secondary source? Does the critic's background suggest that he/she is qualified? After crafting a thesis, consider one of the following two approaches to writing a research paper: Excited about your thesis and eager to begin? Return to the primary or secondary source to find support for your thesis. Organize ideas and begin writing your first draft. After writing the first draft, have it reviewed by your peers and your instructor. Ponder their suggestions and return to the sources to answer still-open questions. Document facts and opinions from secondary sources. Remember, secondary sources can never substitute for primary sources. Confused about where to start? Use your thesis to guide you to primary and secondary sources. Secondary sources can help you clarify your position and find a direction for your paper. Keep a working bibliography. You may not use all the sources you record, but you cannot be sure which ones you will eventually discard. Create a working outline as you research. This outline will, of course, change as you delve more deeply into your subject. A Variety of Information Sources Back to Top "A mind that is stretched to a new idea never returns to its original dimension." --Oliver Wendell Holmes Your thesis and your working outline are the primary compasses that will help you navigate the variety of sources available. In "Introduction to the Library" (5-6) the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers suggests you become familiar with the library you will be using by: taking a tour or enrolling for a brief introductory lecture referring to the library's publications describing its resources introducing yourself and your project to the reference librarian The MLA Handbook also lists guides for the use of libraries (5), including: Jean Key Gates, Guide to the Use of Libraries and Information Sources (7th ed., New York: McGraw, 1994). Thomas Mann, A Guide to Library Research Methods (New York: Oxford UP, 1987). Online Central Catalog Most libraries have their holdings listed on a computer. The online catalog may offer Internet sites, Web pages and databases that relate to the university's curriculum. It may also include academic journals and online reference books. Below are three search techniques commonly used online: Index Search: Although online catalogs may differ slightly from library to library, the most common listings are by: Subject Search: Enter the author's name for books and article written about the author. Author Search: Enter an author's name for works written by the author, including collections of essays the author may have written about his/her own works. Title Search: Enter a title for the screen to list all the books the library carries with that title. Key Word Search/Full-text Search: A one-word search, e.g., 'Kennedy,' will produce an overwhelming number of sources, as it will call up any entry that includes the name 'Kennedy.' To focus more narrowly on your subject, add one or more key words, e.g., "John Kennedy, Peace Corps." Use precise key words. Boolean Search: Boolean Search techniques use words such as "and," "or," and "not," which clarify the relationship between key words, thus narrowing the search. Take Efficient Notes Back to Top Keeping complete and accurate bibliography and note cards during the research process is a time (and sanity) saving practice. If you have ever needed a book or pages within a book, only to discover that an earlier researcher has failed to return it or torn pages from your source, you understand the need to take good notes. Every researcher has a favorite method for taking notes. Here are some suggestions-- customize one of them for your own use. Bibliography cards There may be far more books and articles listed than you have time to read, so be selective when choosing a reference. Take information from works that clearly relate to your thesis, remembering that you may not use them all. Use a smaller or a different color card from the one used for taking notes. Write a bibliography card for every source. Number the bibliography cards. On the note cards, use the number rather than the author's name and the title. It's faster. Another method for recording a working bibliography, of course, is to create your own database. Adding, removing, and alphabetizing titles is a simple process. Be sure to save often and to create a back-up file. A bibliography card should include all the information a reader needs to locate that particular source for further study. Most of the information required for a book entry (Gibaldi 112): Author's name Title of a part of the book [preface, chapter titles, etc.] Title of the book Name of the editor, translator, or compiler Edition used Number(s) of the volume(s) used Name of the series Place of publication, name of the publisher, and date of publication Page numbers Supplementary bibliographic information and annotations Most of the information required for an article in a periodical (Gibaldi 141): Author's name Title of the article Name of the periodical Series number or name (if relevant) Volume number (for a scholarly journal) Issue number (if needed) Date of publication Page numbers Supplementary information For information on how to cite other sources refer to your So you want to study history page . Note Cards Back to Top Take notes in ink on either uniform note cards (3x5, 4x6, etc.) or uniform slips of paper. Devote each note card to a single topic identified at the top. Write only on one side. Later, you may want to use the back to add notes or personal observations. Include a topical heading for each card. Include the number of the page(s) where you found the information. You will want the page number(s) later for documentation, and you may also want page number(s)to verify your notes. Most novice researchers write down too much. Condense. Abbreviate. You are striving for substance, not quantity. Quote directly from primary sources--but the "meat," not everything. Suggestions for condensing information: Summary: A summary is intended to provide the gist of an essay. Do not weave in the author's choice phrases. Read the information first and then condense the main points in your own words. This practice will help you avoid the copying that leads to plagiarism. Summarizing also helps you both analyze the text you are reading and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses (Barnet and Bedau 13). Outline: Use to identify a series of points. Paraphrase, except for key primary source quotations. Never quote directly from a secondary source, unless the precise wording is essential to your argument. Simplify the language and list the ideas in the same order. A paraphrase is as long as the original. Paraphrasing is helpful when you are struggling with a particularly difficult passage. Be sure to jot down your own insights or flashes of brilliance. Ralph Waldo Emerson warns you to "Look sharply after your thoughts. They come unlooked for, like a new bird seen on your trees, and, if you turn to your usual task, disappear...." To differentiate these insights from those of the source you are reading, initial them as your own. (When the following examples of note cards include the researcher's insights, they will be followed by the initials N. R.) When you have finished researching your thesis and you are ready to write your paper, organize your cards according to topic. Notecards make it easy to shuffle and organize your source information on a table-- or across the floor. Maintain your working outline that includes the note card headings and explores a logical order for presenting them in your paper. IV. Begin Thinking, Researching, Organizing Back to Top Don't be too sequential. Researching, writing, revising is a complex interactive process. Start writing as soon as possible! "The best antidote to writer's block is--to write." (Klauser 15). However, you still feel overwhelmed and are staring at a blank page, you are not alone. Many students find writing the first sentence to be the most daunting part of the entire research process. Be creative. Cluster (Rico 28-49). Clustering is a form of brainstorming. Sometimes called a web, the cluster forms a design that may suggest a natural organization for a paper. Here's a graphical depiction of brainstorming . Like a sun, the generating idea or topic lies at the center of the web. From it radiate words, phrases, sentences and images that in turn attract other words, phrases, sentences and images. Put another way--stay focused. Start with your outline. If clustering is not a technique that works for you, turn to the working outline you created during the research process. Use the outline view of your word processor. If you have not already done so, group your note cards according to topic headings. Compare them to your outline's major points. If necessary, change the outline to correspond with the headings on the note cards. If any area seems weak because of a scarcity of facts or opinions, return to your primary and/or secondary sources for more information or consider deleting that heading. Use your outline to provide balance in your essay. Each major topic should have approximately the same amount of information. Once you have written a working outline, consider two different methods for organizing it. Deduction: A process of development that moves from the general to the specific. You may use this approach to present your findings. However, as noted above, your research and interpretive process should be inductive. Deduction is the most commonly used form of organization for a research paper. The thesis statement is the generalization that leads to the specific support provided by primary and secondary sources. The thesis is stated early in the paper. The body of the paper then proceeds to provide the facts, examples, and analogies that flow logically from that thesis. The thesis contains key words that are reflected in the outline. These key words become a unifying element throughout the paper, as they reappear in the detailed paragraphs that support and develop the thesis. The conclusion of the paper circles back to the thesis, which is now far more meaningful because of the deductive development that supports it. Chronological order A process that follows a traditional time line or sequence of events. A chronological organization is useful for a paper that explores cause and effect. Parenthetical Documentation Back to Top The Works Cited page, a list of primary and secondary sources, is not sufficient documentation to acknowledge the ideas, facts, and opinions you have included within your text. The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers describes an efficient parenthetical style of documentation to be used within the body of your paper. Guidelines for parenthetical documentation: "References to the text must clearly point to specific sources in the list of works cited" (Gibaldi 184). Try to use parenthetical documentation as little as possible. For example, when you cite an entire work, it is preferable to include the author's name in the text. The author's last name followed by the page number is usually enough for an accurate identification of the source in the works cited list. These examples illustrate the most common kinds of documentation. Documenting a quotation: Ex. "The separation from the personal mother is a particularly intense process for a daughter because she has to separate from the one who is the same as herself" (Murdock 17). She may feel abandoned and angry. Note: The author of The Heroine's Journey is listed under Works Cited by the author's name, reversed--Murdock, Maureen. Quoted material is found on page 17 of that book. Parenthetical documentation is after the quotation mark and before the period. Documenting a paraphrase: Ex. In fairy tales a woman who holds the princess captive or who abandons her often needs to be killed (18). Note: The second paraphrase is also from Murdock's book The Heroine's Journey. It is not, however, necessary to repeat the author's name if no other documentation interrupts the two. If the works cited page lists more than one work by the same author, include within the parentheses an abbreviated form of the appropriate title. You may, of course, include the title in your sentence, making it unnecessary to add an abbreviated title in the citation. > Prepare a Works Cited Page Back to Top There are a variety of titles for the page that lists primary and secondary sources (Gibaldi 106-107). A Works Cited page lists those works you have cited within the body of your paper. The reader need only refer to it for the necessary information required for further independent research. Bibliography means literally a description of books. Because your research may involve the use of periodicals, films, art works, photographs, etc. "Works Cited" is a more precise descriptive term than bibliography. An Annotated Bibliography or Annotated Works Cited page offers brief critiques and descriptions of the works listed. A Works Consulted page lists those works you have used but not cited. Avoid using this format. As with other elements of a research paper there are specific guidelines for the placement and the appearance of the Works Cited page. The following guidelines comply with MLA style: The Work Cited page is placed at the end of your paper and numbered consecutively with the body of your paper. Center the title and place it one inch from the top of your page. Do not quote or underline the title. Double space the entire page, both within and between entries. The entries are arranged alphabetically by the author's last name or by the title of the article or book being cited. If the title begins with an article (a, an, the) alphabetize by the next word. If you cite two or more works by the same author, list the titles in alphabetical order. Begin every entry after the first with three hyphens followed by a period. All entries begin at the left margin but subsequent lines are indented five spaces. Be sure that each entry cited on the Works Cited page corresponds to a specific citation within your paper. Refer to the the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (104- 182) for detailed descriptions of Work Cited entries. Citing sources from online databases is a relatively new phenomenon. Make sure to ask your professor about citing these sources and which style to use. V. Draft, Revise, Rewrite, Rethink Back to Top "There are days when the result is so bad that no fewer than five revisions are required. In contrast, when I'm greatly inspired, only four revisions are needed." --John Kenneth Galbraith Try freewriting your first draft. Freewriting is a discovery process during which the writer freely explores a topic. Let your creative juices flow. In Writing without Teachers , Peter Elbow asserts that "[a]lmost everybody interposes a massive and complicated series of editings between the time words start to be born into consciousness and when they finally come off the end of the pencil or typewriter [or word processor] onto the page" (5). Do not let your internal judge interfere with this first draft. Creating and revising are two very different functions. Don't confuse them! If you stop to check spelling, punctuation, or grammar, you disrupt the flow of creative energy. Create; then fix it later. When material you have researched comes easily to mind, include it. Add a quick citation, one you can come back to later to check for form, and get on with your discovery. In subsequent drafts, focus on creating an essay that flows smoothly, supports fully, and speaks clearly and interestingly. Add style to substance. Create a smooth flow of words, ideas and paragraphs. Rearrange paragraphs for a logical progression of information. Transition is essential if you want your reader to follow you smoothly from introduction to conclusion. Transitional words and phrases stitch your ideas together; they provide coherence within the essay. External transition: Words and phrases that are added to a sentence as overt signs of transition are obvious and effective, but should not be overused, as they may draw attention to themselves and away from ideas. Examples of external transition are "however," "then," "next," "therefore." "first," "moreover," and "on the other hand." Internal transition is more subtle. Key words in the introduction become golden threads when they appear in the paper's body and conclusion. When the writer hears a key word repeated too often, however, she/he replaces it with a synonym or a pronoun. Below are examples of internal transition. Transitional sentences create a logical flow from paragraph to paragraph. Iclude individual words, phrases, or clauses that refer to previous ideas and that point ahead to new ones. They are usually placed at the end or at the beginning of a paragraph. A transitional paragraph conducts your reader from one part of the paper to another. It may be only a few sentences long. Each paragraph of the body of the paper should contain adequate support for its one governing idea. Speak/write clearly, in your own voice. Tone: The paper's tone, whether formal, ironic, or humorous, should be appropriate for the audience and the subject. Voice: Keep you language honest. Your paper should sound like you. Understand, paraphrase, absorb, and express in your own words the information you have researched. Avoid phony language. Sentence formation: When you polish your sentences, read them aloud for word choice and word placement. Be concise. Strunk and White in The Elements of Style advise the writer to "omit needless words" (23). First, however, you must recognize them. Keep yourself and your reader interested. In fact, Strunk's 1918 writing advice is still well worth pondering. First, deliver on your promises. Be sure the body of your paper fulfills the promise of the introduction. Avoid the obvious. Offer new insights. Reveal the unexpected. Have you crafted your conclusion as carefully as you have your introduction? Conclusions are not merely the repetition of your thesis. The conclusion of a research paper is a synthesis of the information presented in the body. Your research has led you to conclusions and opinions that have helped you understand your thesis more deeply and more clearly. Lift your reader to the full level of understanding that you have achieved. Revision means "to look again." Find a peer reader to read your paper with you present. Or, visit your college or university's writing lab. Guide your reader's responses by asking specific questions. Are you unsure of the logical order of your paragraphs? Do you want to know whether you have supported all opinions adequately? Are you concerned about punctuation or grammar? Ask that these issues be addressed. You are in charge. Here are some techniques that may prove helpful when you are revising alone or with a reader. When you edit for spelling errors read the sentences backwards. This procedure will help you look closely at individual words. Always read your paper aloud. Hearing your own words puts them in a new light. Listen to the flow of ideas and of language. Decide whether or not the voice sounds honest and the tone is appropriate to the purpose of the paper and to your audience. Listen for awkward or lumpy wording. Find the one right word, Eliminate needless words. Combine sentences. Kill the passive voice. Eliminate was/were/is/are constructions. They're lame and anti-historical. Be ruthless. If an idea doesn't serve your thesis, banish it, even if it's one of your favorite bits of prose. In the margins, write the major topic of each paragraph. By outlining after you have written the paper, you are once again evaluating your paper's organization. OK, you've got the process down. Now execute! And enjoy! It's not everyday that you get to make history. VI. For Further Reading: Works Cited Back to Top Barnet, Sylvan, and Hugo Bedau. Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing: A Brief Guide to Argument. Boston: Bedford, 1993. Brent, Doug. Reading as Rhetorical Invention: Knowledge,Persuasion and the Teaching of Research-Based Writing. Urbana: NCTE, 1992. Elbow, Peter. Writing without Teachers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. Gibladi, Joseph. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 4th ed. New York: Modern Language Association, 1995. Horvitz, Deborah. "Nameless Ghosts: Possession and Dispossession in Beloved." Studies in American Fiction , Vol. 17, No. 2, Autum, 1989, pp. 157-167. Republished in the Literature Research Center. Gale Group. (1 January 1999). Klauser, Henriette Anne. Writing on Both Sides of the Brain: Breakthrough Techniques for People Who Write. Philadelphia: Harper, 1986. Rico, Gabriele Lusser. Writing the Natural Way: Using Right Brain Techniques to Release Your Expressive Powers. Los Angeles: Houghton, 1983. Sorenson, Sharon. The Research Paper: A Contemporary Approach. New York: AMSCO, 1994. Strunk, William, Jr., and E. B. White. The Elements of Style. 3rd ed. New York: MacMillan, 1979. Back to Top This guide adapted from materials published by Thomson Gale, publishers. For free resources, including a generic guide to writing term papers, see the Gale.com website , which also includes product information for schools. National Council on Public HistoryHOW DO HISTORIANS KNOW ABOUT THE PAST? There are many different ways of exploring and thinking about the past, and many different ways to use that knowledge . Professional historians—people with some advanced training in the discipline of history—bring a particular and often-misunderstood set of skills to the task of learning about the past. They gather and weigh different kinds of evidence , including primary sources (documents or recollections from the time period being studied), material artifacts, and previous scholarship (secondary sources). Using these sources, they work toward careful, often provisional interpretations of what was happening and why at a given time. Above all, historians are trying to understand how and why things change over time . This isn’t a matter of simply pinpointing causes and outcomes, but of considering different contexts and time scales for interpreting the available facts. For example, the history of conflict in the Middle East is often seen as the result of religious clashes going back centuries or millennia. But it can also be interpreted in light of the history of European intervention and colonization in the region, as well as the shorter timeline of other nations’ reliance on Middle Eastern oil. Historians weigh these kinds of time frames and intersecting processes to arrive at accounts of the past that go beyond simple cause and effect. Good historical thinking seldom provides easy answers or lessons. But it can help to clarify what’s at stake, what has shaped present-day realities, and who has been involved in (or excluded from) particular struggles and changes. Public historians put these skills to work in many different settings, from museums and government agencies to projects that help communities document their own histories. (Click here to see some of the kinds of work public historians do.) Visit the History Relevance Campaign for another statement about the importance and use of historical thinking. For an in-depth podcast series featuring interviews with historians about how they work, listen to Doing History from the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, in collaboration with Ben Franklin’s World: A Podcast about Early American History . Sign Up to Receive News and Announcements Emails from NCPH- Only members receive our weekly e-newsletter, but on occasion we send news and announcements to broader audiences. This includes information about our annual meeting and other events, advocacy alerts, and opportunities in the public history field.

- Name * First Last

- Annual Meeting Information

- NCPH News and Announcements

- NCPH Advocacy Efforts

- News and opportunities from NCPH Affiliates

- I have read and understood the Privacy Statement

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

You may unsubscribe or change your preferences at anytime by emailing [email protected] Cavanaugh Hall 127, 425 University Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46202-5140 (317) 274-2716 [email protected]  How Historians Write About HistoryHow do historians write about the people, places, and events they’ve studied in historical sources? We continue our Doing History: How Historians Work series by investigating how historians write about history. Our guide for this investigation is John Demos, the Samuel Knight Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University and an award-winning historian.  Episode Summary In this episode, we explore how historians write about history with John Demos, the Samuel Knight Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University and an award-winning historian. During our conversation, John reveals what the new social and new narrative schools of history are and what it’s like to write about history in those genres; How John decides whether he should write a book about his research topics; And, how John approaches writing and has developed his writing skills over time. What You’ll Discover- John’s love of writing and how he became a historian

- New social history

- New narrative history

- John’s 3 dimensions of historical study: 1. Particular 2. General 3. Generic

- The importance of people in historical writing

- Details about the “heathen school” in Cornwall, Connecticut (1817-1826)

- How John decides whether his research topic is a book

- John’s writing process

- How John knows when to stop conducting research

- Mistakes John has made in his writing

- How to weave historical analysis into a compelling narrative

- How John developed his writer’s voice

- How historians balance a desire to do justice to the past with their position as human beings in the 21st century

- How John tries to maintain objectivity when he writes about history

Links to People, Places, and Publications- Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England

- The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America

- The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Age of the Early Republic

- Aaron Sachs

- Wallace Stegner, Angle of Repose

- The New Yorker

- John’s Potosi article for Common-place

Recent posts- History & Historians in the Public April 27, 2020

- The History of Genealogy April 20, 2020

- How Genealogists Research April 13, 2020

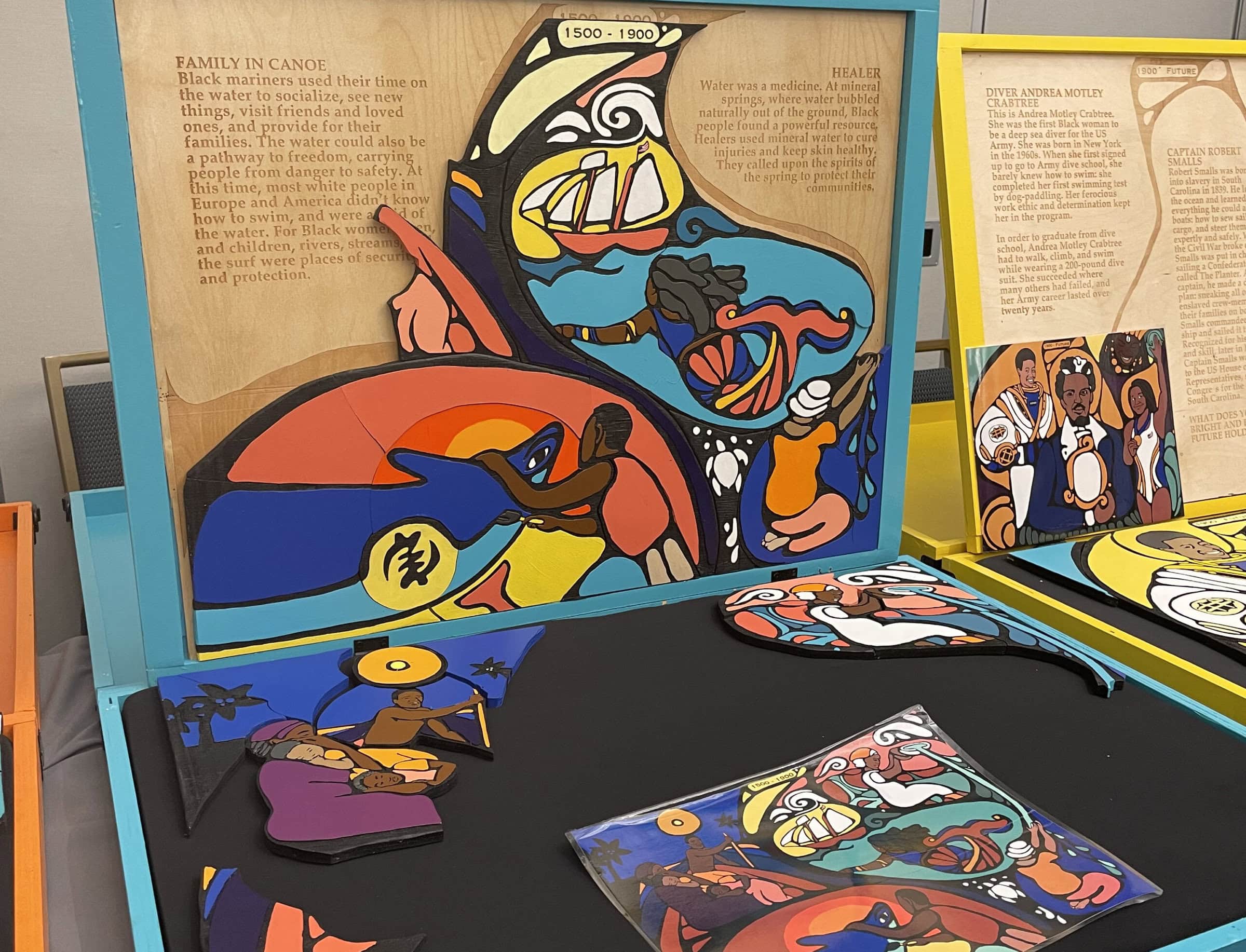

Follow @DoingHistoryPod Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices. 26 Becoming a Public HistorianA public historian is someone who makes historical knowledge available to the general public. The historian may be a trained academic historian, a person with specialized training in the craft of public history, or an avocational historian who shares their knowledge. Each type has its own advantages and limitations. Academically trained historians : These public historians can be confident that they are well-trained in how to make meaning out of historical evidence, often by applying theoretical frameworks primarily understood by others with similar advanced training. That sentence contains most of their strengths and weaknesses for doing public history. The public is happy to see pieces of historical evidence-objects, photographs, and documents. The public is less happy with theories, jargon or anything else that makes them feel unwelcome. The academically trained public historian should change the way they communicate information about history. U se accessible language and appeal to a wide variety of interests and levels of dedication among learners. The typical trained public historian receives their undergraduate and/or graduate degree in public history or museum studies. They should be well prepared to communicate history to the public. They may not have as much training in sophisticated thinking about history. The public may not like theories but their learning experience can be richer if the message is crafted by someone with a deep understanding of historiography. A good researcher can quickly amass enough understanding of any particular historic event or issue to build a credible public history presentation. A lack of deep understanding could, however make that presentation a bit flat, or superficial. Also, the public will only forgive a mistake, or a demonstrated lack of detailed knowledge, if the historian is ready to learn alongside them. The trained public historian need s to cultivate a passion for some particular areas of history and to pursue understanding of sophisticated historiography. The amateur historian enjoys comfortable membership in the public that forms the audience of public history, and may have the easiest time reaching the audience. Such a historian generally studies a limited range of subjects in which they have a passionate interest. They do this in their leisure time while pursuing some other career that may not relate to history. They may have no formal history training beyond high school learning or undergraduate survey courses. If they are personable, their passion for their subject shines through to engage audiences. Their limitations are also born of that passion. They may focus on intense knowledge of objects and facts and assume the audience wants to learn absolutely every detail. They may also fail to give an overall framework into which the learner can place these discrete facts in order to understand them—that is, fail to give context. Passion can produce giant exhibits, long, exhausting writings, and two-hour lectures. The amateur historian must harness their passion and give the learner the opportunity to take in small or large servings of the historian’s wealth of knowledge. Every public historian needs to do ALL of the things in italics and is prone to all of the mistakes. Public History’s AudienceThe audience for public history is, ideally, everyone. We all know the popular arguments for the value of studying history: learn about the past so as to avoid repeating old mistakes; you must study the origin and progress of your family, city, nation, political group, ethnic or racial group, profession or philosophy, in order to understand yourself; study the history of groups to which you do not belong, so as to better understand the world. Good public history accomplishes such valuable goals. Unlike the audience for academic history, the casual learner may not be drawn by intense interest and may have absolutely no basis of existing knowledge. Even worse, they may have inaccurate existing knowledge that they resist questioning. The actually resistant learner is the hardest of all. Think of the person whose family dragged them to your museum when they had other plans. Think of students assigned to do your fun online history tutorial who do not think history can be fun. Meet each learner on their own terms and try to respond to their interest level. Take failure in stride and revel in even a tiny victory of sparked interest. The number one job of the public historian—InterpretationPublic history is all, ultimately, interpretation. It is the act of transforming the raw knowledge from primary sources and the complex conclusions produced by academic inquiry into accessible presentations. Difficult, but worth the struggle. A formalized understanding of the craft of interpretation was made available in 1957. Working with the National Park Service, Freeman Tilden wrote Interpreting Our Heritage as a guide for those who led tours in national parks. His six principals of interpretation were designed for use on tours of the natural world and discussions of larger environmental issues. They work equally well for a historic artifact or document. The constant evolution of the practice of public history has never rendered his basic ideas obsolete. His short book is a quick read and highly recommended. Here is a list of suggestions for good interpretation: - Creating interpretation that is accessible does not mean “dumbing down” sophisticated ideas. It is much more difficult than that! It involves careful use of familiar language and skilled use of images and objects to form a message that people with an amateur interest in history can find helpful and intriguing.

- Public history meets learners where they are. A skilled presentation serves as an introduction for those who know nothing about the subject, and provides new information for those already invested in the subject.

- Learners may arrive expecting to be given facts. That would be poor interpretation. Better they leave without a single new fact in their head but with an experience of questioning, of critical thinking, of wanting to know more. Tilden said, “The chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.” What do you think a learner remembers longest-a date in history, or the controversy over the meaning of whatever happened on that date?

- Interpretation must be geared to all possible learners, of every age, education level, background or religion, and great efforts should be made to properly include groups previously excluded from discussions of history. Good interpretation is for everybody.

- It is impossible to create interpretation that works equally well for everybody. This dichotomy is for the public historian to resolve with creativity, flexibility and love. (It is rather similar to the problem caused by these two rules of exhibit design: Labels should be brief so they will be read. Labels should be full of information so they are informative and provocative. Good luck with that one!)

- Tilden also said interpretation is an art, and a process. Doing it well takes practice, mastering an art. The idea of process can inform the crafting of any individual interpretive effort, that is, its structure represents a process of introducing the topic and moving through stages of increasing information and active evaluation that includes the learner. One hopes that each interpretive act is but one part of a larger intellectual journey for the learner. Leave them wanting more.

- Interpretation must be true. That sounds obvious but gives rise to so many questions. Is an exhibit offering true interpretation if one of the artifacts is a reproduction? Maybe, maybe not. If you simplify a map of seventeenth-century Europe, de-emphasizing some of the less active countries, is that making the political geography of the time accessible or is it falsification? Probably both. If your audience is bored and drifting, should you spice up your presentation with an amusing anecdote of questionable veracity? That would be tempting, but not good public history, despite the advice in item 7.

- Learners are not looking for an intense boot camp of study followed by a grueling examination. The public historian does not give grades. The learner can leave in the middle if they wish. Like any purveyor of leisure, you must attract and hold their attention. Humor can help, even bad jokes. Horror can help. Few visitors can ignore a display of a Ku Klux Klan robe. They become like drivers entranced by a highway accident. Popular culture references work sometimes, if carefully targeted and explained. Interpretation is a conversation, a performance, a seduction.

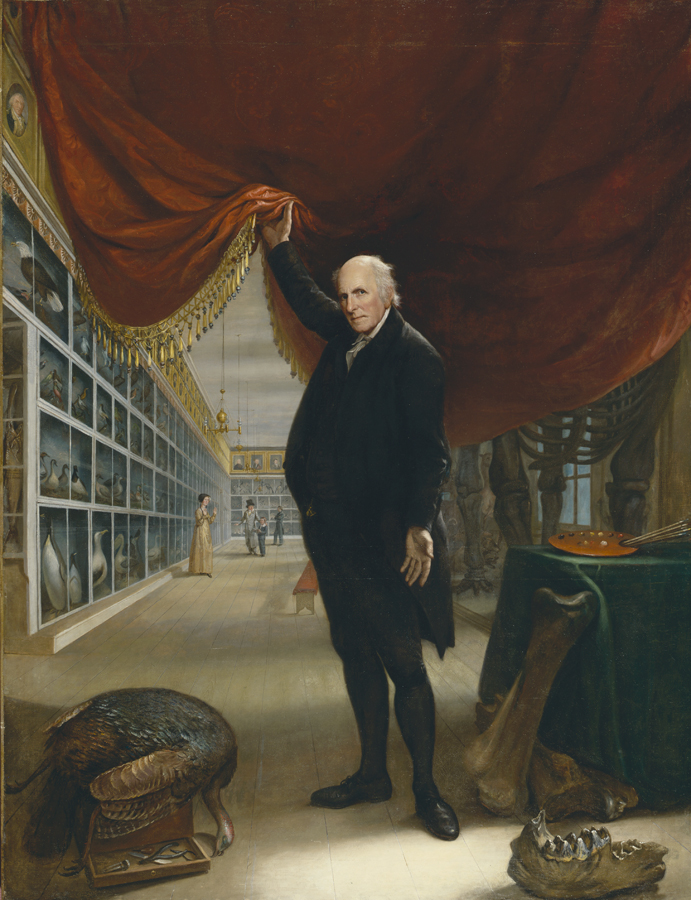

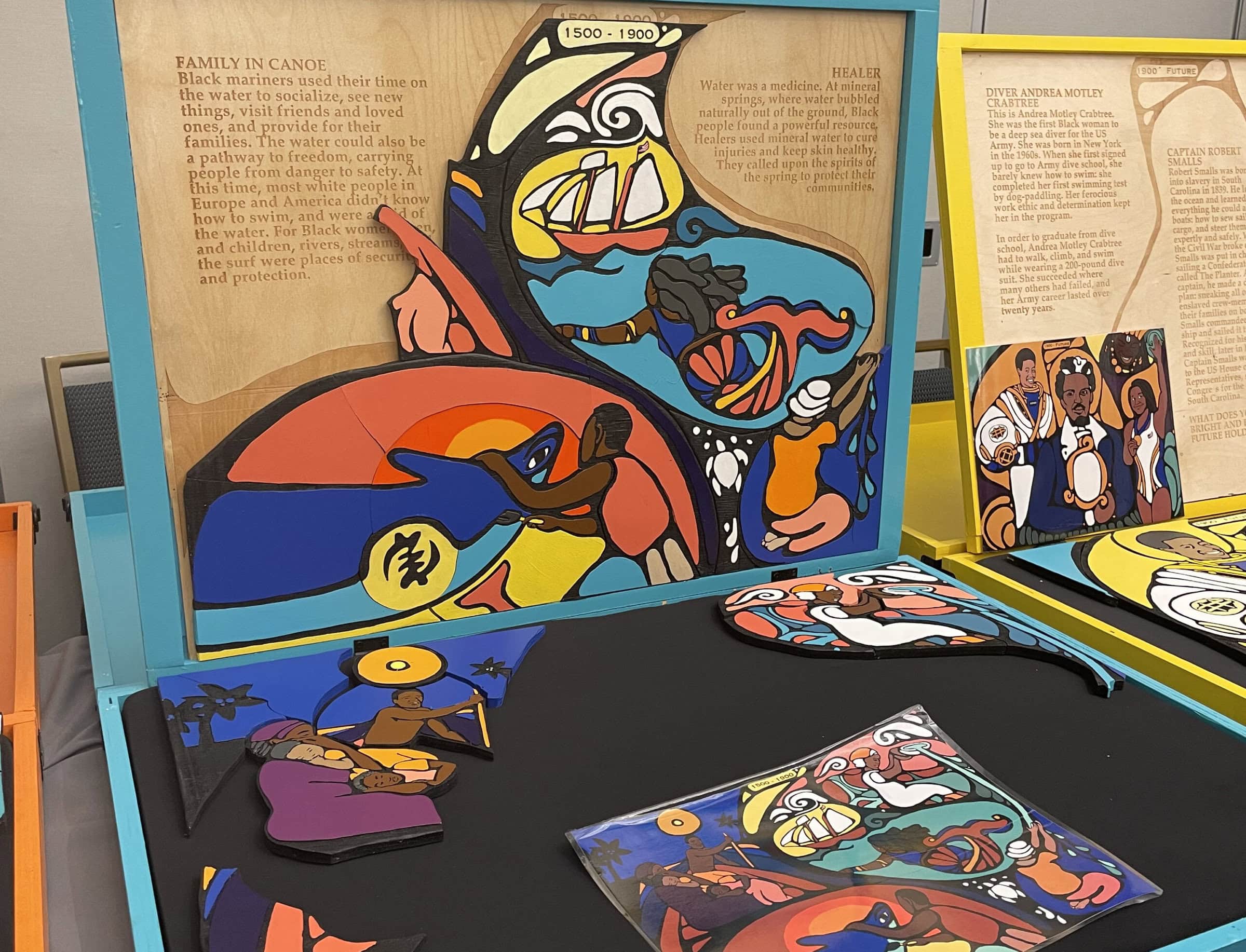

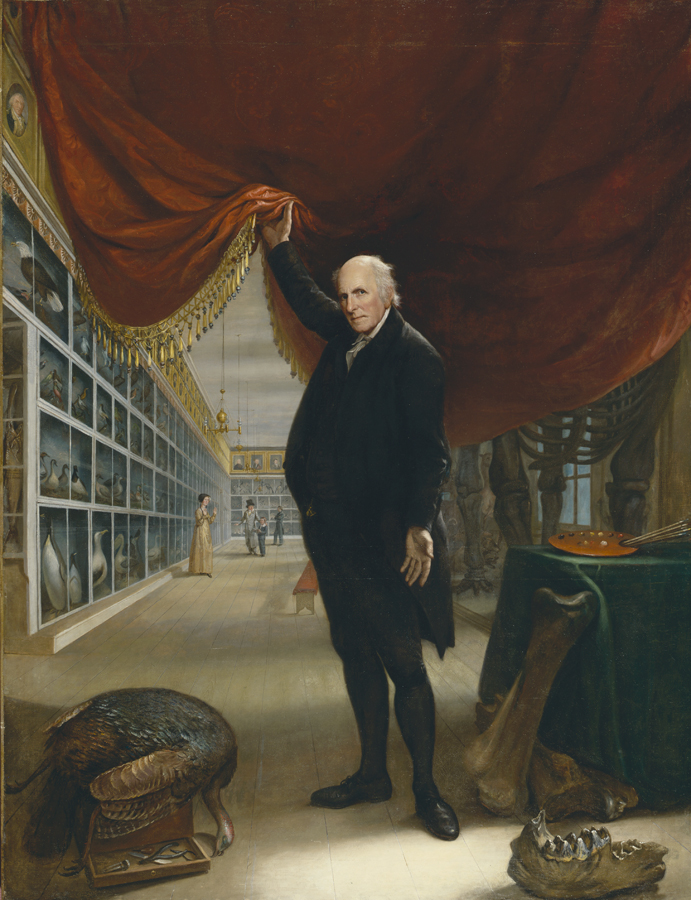

History MuseumsHistory museums may be the first place aspiring public historians consider working. They are also the first choice of potential learners. Authors Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen conducted a poll of 1,500 Americans, asking about their relationship to history, and published the results in The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life in 1998. Museums were the most trusted source of information, far ahead of respondents’ history teachers or even their own grandparents. The earliest museums in the United States presented collections of interesting or exotic objects. They did not strictly adhere to divisions of subject matter, with separate museums for history or science. They lacked even the most rudimentary interpretation An excellent example of the early museum was created by Charles Wilson Peale (1741-1827) in Philadelphia. Peale was an artist who captured the likenesses of many leaders of the American Revolution. His townhouse included a large studio space, which became the first museum gallery, opening in 1786. Peale became a collector, the avocation of many early museum builders. Studio visitors admired his displayed objects, thus inspiring the museum. He mostly collected natural history specimens. He displayed bones, including a Mastodon skeleton, and taxidermied specimens of animals, both strange and familiar. He also displayed his own portraits of inspirational American heroes and some Revolutionary War relics. As a compatriot of Benjamin Franklin, it is not surprising that he included examples of recent inventions. He created a large format “cabinet of curiosities,” the term for a domestic display of objects by an amateur collector.  His self-portrait titled “The Artist in His Museum,” depicts the tasteful arrangement of his collection when it was displayed at Independence Hall. We see him at age 81, in 1822, as he lifts the curtain to reveal the secrets of the world. Beyond the curtain we see animal specimens arranged according to the fairly new idea of taxonomy of living things, so that the birds are grouped together. Above are his American hero portraits. Clearly there was an order to the display, and that is a key first step toward providing the viewer with helpful interpretation. But there was little to no signage (or live gallery guides to answer question) to explain the objects, their origin, arrangement and why they merited inclusion. The well-dressed visitors we see in the background were left to observe without direction, unless the collector himself happened along to chat. Everything has changed since then. Museums small and large proliferated and refined their practices. The main change was away from objects valued mostly for the thrill of possessing that which was rare or exotic or nostalgic toward using them to gain larger historic knowledge. The early collectors, often referred to by the slightly pejorative term “antiquarians,” did not always do that. Often their interest was limited to information about the object’s origin story, including who made it and where, what materials were used, what style might its decoration represent; and its rarity. All of those are good starting points for teaching, but not whole story. Museums evolved, increasingly presenting the object’s role in larger historical trends. The artifacts themselves were arranged in thematic groupings, to add understanding of their connections. Dioramas and room settings were created to give a more tangible feel of historic environments and how collected objects fit into them. Historic house museums took this method further. Gallery rooms could also group artifacts and their accompanying information by time period, association with specific groups of people, or stages of technological production. Labels and signage explained what the visitor was viewing. This is not to suggest that museums achieved perfection. Racism and ethnocentrism haunted curatorial decisions, even in exhibits about foreign cultures and people of color. Great men dominated, with occasional cameo appearances by supporting women like Betsy Ross. Elitism was rampant. Displays of domestic objects and room presented the lives of the wealthy, not the everyday environments of other social groups. The initial audiences for museums were expected to be limited to educated members of the upper social classes, like the people Peale painted visiting his museum. Other people might be dismissed as unable to profit from the knowledge made available in museums. By the Victorian era and into the twentieth century, this thinking changed. Those who were often termed the “common man” were seen as good candidates for visiting a museum. Once there, they would learn from carefully curated presentations of patriotic interpretation, designed to reinforce reverence for the existing social and political systems. Immigrant visitors could learn how to think like Americans. Poorer Americans could embrace middle-class values and norms. Children would be directed to an unwaveringly positive view of their heritage and nation. This sort of practice reached new heights during World War II and the Cold War era. Museums helped remind soldiers going to Europe and post-war civilians of the reasons to support national initiatives. 1976 may have been the last big hurrah for those ideas in museums. The Bicentennial inspired the creation of endless small local history museums and special exhibits in established ones. This curatorial tradition of telling visitors what they should think and what they should learn likely contributed to the later backlash against curatorial authority. So did the perceived curatorial focus on collecting as the major purpose of the museum, with education given less respect. The high point of the backlash was the 2010 publication of The Participatory Museum by Nina Simon, which is available to read free online. This began a conversation within the museum community about the importance of making the museum’s wealth of information available to all visitors in a spirit of discussion and equality. The ongoing experiment is producing strategies for balancing the value of collections and meaningful education with equal regard for both. Advanced training in history is valuable, and often required, for any position in a history museum. The staff who most actively use the skills of the historian are in the education and curatorial departments. Keep in mind the vast range of museum sizes. Some have only one full-time employee who does almost everything. Some have hundreds of people. Educators share the museum’s information with everybody they possibly can. Their methods can include classes for adults or children, lectures and book discussions, tours of the museum, presentations in schools, designing activities for specialized children’s areas within the museum, and offering educational crafts and games during special events. They plan and oversee field trips. This requires logistical expertise and customer service ability, as well as knowledge of curriculum and local education standards so that the field trip activities meet the needs of the schools. Educators take part in exhibit creation and all events and interpretive planning in the museum. The curatorial department is responsible for assembling, maintaining and understanding the museum’s collection of historic materials. They use the collection to create exhibits for their museum, for travel to other museums, and online. They may produce other informative offerings, such as videos or publications. They will almost certainly be asked to provide tours of the museum collection, discuss interesting collection pieces online, and work with students. They also make the collection available for scholarly study. In a small museum, one curator may be both the historian and the person who cares physically for the collection. Ideally a separate collections manager is responsible for all aspects of collection care. Physical care ranges from dusting to hiring professions to restore an artifact. The collections manager knows what and where everything is, as well as how it came to the collection, and if it is sturdy or on the verge of disintegration. They oversee the safe storage, handling and exhibit use of artifacts. In a very large staff there may be positions for archivists, specialized curators, conservators (trained in artifact repair), photographers and exhibit builders. A public historian who does well may become the director of the museum. If you have this opportunity, do not let the financial spreadsheets and endless courting of donors make you forget that you are a historian. Other Career Options in Public HistoryCareers outside of the museum also involve various ways of communicating your understanding of history to those seeking to increase theirs. Where museum work offers the chance to work with historic objects and documents and to craft and carry out exhibits and instructive interactions with the public, some of these alternatives allow you to focus more on one of those areas. The public historian’s thoughtful, accessible interpretation of history can take effective form as writing. Of course, we are past the time “publishing” only referred to printed material like books and magazines, but they are not dead yet and so merit consideration. Written public history is less burdened with the need to address reluctant learners. Except for student assignments, the disinterested will never be part in your audience! All the goals of interpretation apply to writing. It must be authentic, engaging, welcoming, overtly informative and sneakily more than the learner expected. Language is important and visuals are highly recommended. Other roles including editing, developing new authors and fields, and promoting books allow the lucky job candidate to work with many historical subjects while enjoying regular employment and benefits. Authors are more likely to be self-employed, though opportunities exist within history organizations that do publication. We now have so many options beyond books. Technology and creative ways to use it offer constant opportunities to interpret for the connected public. There is little point in discussing specific current technological products—as they will soon change. The wonders of new tools should never overshadow the rules of good interpretation. The field has left behind the days when digital methods of communication were suspect. All acts of interpretation are judged by the same standards. Fiction is controversial. Novels and films featuring a dramatic or humorous fictional tale set into an (hopefully) accurate historic setting are a complicated issue. The learner, who may think they are casually relaxing with a film or an historical romance, is also studying the past. What an opportunity for the public historian—you have their willing attention! Unfortunately, the most memorable parts tend to be the fights, love scenes and jokes, rather than the background of historical events like political differences and the failures of business. Consider the example of the 1997 movie, Titanic. Most viewers remember the nude drawing scene. Many learned a bit about the strict divisions of social class in 1912, since that idea appeared repeatedly and forcefully. Far fewer likely picked up on the hints that the ship’s owners rushed it into use and ignored safety concerns. Whatever the limitation of fictional history authorship, serving as an expert advisor on such productions is a legitimate role for a public historian. Such a consultant reviews proposed clothing, furnishings and backgrounds for a film, insuring that these visual elements are correct. The consultant may be able to address language mistakes, such as having a character say “O.K.” before its period of common use. Like all consulting jobs, this requires prior experience to establish credentials. Cultural Heritage Preservation and Historic PreservationThe more recognized field of historic preservation, in which buildings and landscapes are saved and maintained, is actually a sub-field of cultural heritage preservation. The overall goal of that is to selectively and effectively identify aspects of human culture that should be kept alive and made available to the public for education, celebration and recreation. Historic preservation in the United States is generally thought to have begun with activist women who formed the Mount Vernon Ladies Association in 1853 to save George Washington’s iconic house. They saw the house as a living symbol of the ideals of the American Revolution, practically a shrine. The ladies learned lessons through hard experience that new preservationists still face. They had to find the means of acquiring ownership, establish an efficient governing organization, fundraise endlessly, and decide how best to maintain the building so that it authentically represents what is termed the “period of significance.” For Mount Vernon that is the lifetime of the hero. Their efforts were overtly directed at inculcating patriotism. They even hoped the structure could turn hearts away from sectional division and prevent the impending Civil War. The house could not do that, but its emotional association with General Washington did keep it safe from Union soldiers who destroyed other houses in their path. Modern preservation goes far beyond sanctifying the homes of great men-though there is value in those places. Preservation efforts are now directed at saving places representing all kinds of people, as well as cultural trends such as the history of musical genres or theater. Social history points to many sites worth saving, as can all areas of historical inquiry. Efforts have also moved beyond the protection of individual buildings to protecting neighborhoods, urban streetscapes, and rural and agricultural landscapes. Where can the trained historian find work in this field? Every preservation effort is based on research into the location’s past. The resulting body of knowledge is used in fundraising efforts, public policy decisions and winning citizen support. All are needed to begin the process of preservation. This information guides the physical treatment of the property once preservation begins. For instance, it informs decisions about what parts of the building or landscape should stay because they authentically represent the location’s past, and which should be removed because they do not. Such parts could be as small as a hinge or as big as an orchard or barn. Private firms employ historians to do such research for clients, as do government entities at all levels. They navigate complex issues of legal limits and official policy, as well as economic interest and public sentiment. At the federal level, historians work to guide policy and practice in the National Parks Service and in the offices of the Secretary of the Interior, which sets standards for appropriate preservation and maintains the National Register of Historic Places. At the municipal and county level, employees oversee the proper implementation of preservation work and the designation of significant places. Each state has an affiliate historic preservation office to identify and protect important sites. They work for the state government to properly implement national standards and help local individuals and groups engage in responsible preservation. In Texas, this office is part of the Texas Historical Commission. They also operate historic sites at houses, cemeteries and agricultural grounds for educating visitors. They authorize and create official historic markers that tell passers-by the significance of the place where they are standing. In their public work they cross over from the smaller area of historic preservation to larger aspects of cultural heritage preservation. This large preservation field identifies, saves and disseminates information about all aspects of all relevant cultures. Those include not only buildings and smaller objects of all types, but intangible artifacts like folk songs and stories, religious rituals, family celebratory practices, or anything else that tells how a particular people experienced and explained the world. Some preservation organizations and government agencies employ historians to gather material and make it available, but much work in this area may be individual efforts involving little immediate financial gain. Such study can inform publications of all types as well as museum work. Corporate and Governmental HistoryMany corporations and governmental agencies employ historians and archivists to maintain the entity’s history. Their primary goal in doing this is to insure smooth current operations by giving staff members easy access to information about organizational history. The historian is expected to have the most thorough knowledge of the organization possible, and know where to find the answer to every question. This type of position may therefore be focused on information classification, storage and retrieval. There may still be some opportunities to engage in interpretation to the public. The corporate or departmental historian may be charged with overseeing content about the organization’s history for their website, as well as other digital outreach efforts. They could be called upon for archival images or stories for use in advertising or public relations. They might even be able to assemble a more detailed publication about the history of the organization. One Dallas-Fort Worth example is cosmetic company Mary Kay. They have long maintained an internal historian and a collection of both archival material and objects. This collection is shown in a museum space in the company’s world headquarters in Addison, Texas. The collection of past products and packaging can be referenced for current product development. The record of the company’s history of working with a national, and now international, army of individual sellers is also valuable. They use it to recruit and retain these workers. They promote the history of the company and its founder, Mary Kay Ash, as offering women empowerment and self-sufficiency. As this one example may suggest, an internally employed historian in such a place may be limited in their historic messaging. As an employee, they may be expected to toe the party line. Every organization likely has unflattering aspects in their past that a good historian would want to explore, but might not be allowed to pursue. Consider this before taking either a regular position or a consulting assignment. Also weigh the possibility of encouraging a more transparent and accurate historical interpretation. You might succeed! Archives and LibrariesEach of these institutions requires specialized training in their practices for collecting and organizing books and documents and other types of texts. Subject knowledge is a definite plus for recognizing the potential uses each resource holds for historical study. Skill in interpretation supports the other mission function of such institutions: connecting information seekers with the right resources and helping them make full use of them. As the temporary research assistant for each visitor, the archivist or librarian can explore new knowledge on so many subjects while helping people learn how to research, to think critically, and to synthesize discrete facts into useful historical insights. Recommended resources:Start online with these two organizations. Both offer free information, student memberships, hold yearly conferences and publish journals. The first is slightly more oriented to the practice of public history across all fields. The second tends to focus more on museum issues. - https://ncph.org

- https://aaslh.org

- https://www.oah.org

- https://www.texasmuseums.org

- https://www.thc.texas.gov