- Understanding Poverty

- Disaster Risk Management

Shock Waves : Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty

Ending poverty and stabilizing climate change will be two unprecedented global achievements and two major steps toward sustainable development. But the two objectives cannot be considered in isolation: they need to be jointly tackled through an integrated strategy. This report brings together those two objectives and explores how they can more easily be achieved if considered together.

Publication

Climate Change, Disaster Risk, and the Urban Poor

Analyzing the key challenges the urban poor face from climate change and disasters and identifies strategies and financing opportunities.

You have clicked on a link to a page that is not part of the beta version of the new worldbank.org. Before you leave, we’d love to get your feedback on your experience while you were here. Will you take two minutes to complete a brief survey that will help us to improve our website?

Feedback Survey

Thank you for agreeing to provide feedback on the new version of worldbank.org; your response will help us to improve our website.

Thank you for participating in this survey! Your feedback is very helpful to us as we work to improve the site functionality on worldbank.org.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2022

The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management

- Heidi Kreibich ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6274-3625 1 ,

- Anne F. Van Loon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2308-0392 2 ,

- Kai Schröter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3173-7019 1 , 3 ,

- Philip J. Ward ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7702-7859 2 ,

- Maurizio Mazzoleni ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0913-9370 2 ,

- Nivedita Sairam ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4611-9894 1 ,

- Guta Wakbulcho Abeshu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8775-3678 4 ,

- Svetlana Agafonova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6392-1662 5 ,

- Amir AghaKouchak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4689-8357 6 ,

- Hafzullah Aksoy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5807-5660 7 ,

- Camila Alvarez-Garreton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5381-4863 8 , 9 ,

- Blanca Aznar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6952-0790 10 ,

- Laila Balkhi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8224-3556 11 ,

- Marlies H. Barendrecht ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3825-0123 2 ,

- Sylvain Biancamaria ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6162-0436 12 ,

- Liduin Bos-Burgering ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8372-4519 13 ,

- Chris Bradley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4042-867X 14 ,

- Yus Budiyono ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6288-6527 15 ,

- Wouter Buytaert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6994-4454 16 ,

- Lucinda Capewell 14 ,

- Hayley Carlson 11 ,

- Yonca Cavus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0528-284X 17 , 18 , 19 ,

- Anaïs Couasnon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9372-841X 2 ,

- Gemma Coxon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8837-460X 20 , 21 ,

- Ioannis Daliakopoulos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9333-4963 22 ,

- Marleen C. de Ruiter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5991-8842 2 ,

- Claire Delus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6690-5326 23 ,

- Mathilde Erfurt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1389-451X 19 ,

- Giuseppe Esposito ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5638-657X 24 ,

- Didier François 23 ,

- Frédéric Frappart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4661-8274 25 ,

- Jim Freer 20 , 21 , 26 ,

- Natalia Frolova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3576-285X 5 ,

- Animesh K. Gain ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3814-693X 27 , 28 ,

- Manolis Grillakis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4228-1803 29 ,

- Jordi Oriol Grima 10 ,

- Diego A. Guzmán 30 ,

- Laurie S. Huning ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0296-4255 6 , 31 ,

- Monica Ionita ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8240-4380 32 , 33 , 34 ,

- Maxim Kharlamov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4439-5193 5 , 35 ,

- Dao Nguyen Khoi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1618-1948 36 ,

- Natalie Kieboom ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8497-0204 37 ,

- Maria Kireeva ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8285-9761 5 ,

- Aristeidis Koutroulis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2999-7575 38 ,

- Waldo Lavado-Casimiro ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0051-0743 39 ,

- Hong-Yi Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9807-3851 4 ,

- María Carmen LLasat ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8720-4193 40 , 41 ,

- David Macdonald ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3475-636X 42 ,

- Johanna Mård ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8789-7628 43 , 44 ,

- Hannah Mathew-Richards 37 ,

- Andrew McKenzie ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8723-4325 42 ,

- Alfonso Mejia ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3891-1822 45 ,

- Eduardo Mario Mendiondo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2319-2773 46 ,

- Marjolein Mens 47 ,

- Shifteh Mobini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3365-7346 48 , 49 ,

- Guilherme Samprogna Mohor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2348-6181 50 ,

- Viorica Nagavciuc ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1111-9616 32 , 34 ,

- Thanh Ngo-Duc ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1444-7498 51 ,

- Thi Thao Nguyen Huynh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9071-1225 52 ,

- Pham Thi Thao Nhi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4118-8479 36 ,

- Olga Petrucci ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6918-1135 24 ,

- Hong Quan Nguyen 52 , 53 ,

- Pere Quintana-Seguí ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7107-9671 54 ,

- Saman Razavi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1870-5810 11 , 55 , 56 ,

- Elena Ridolfi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4714-2511 57 ,

- Jannik Riegel 58 ,

- Md Shibly Sadik ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9205-4791 59 ,

- Elisa Savelli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8948-0316 43 , 44 ,

- Alexey Sazonov 5 , 35 ,

- Sanjib Sharma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2735-1241 60 ,

- Johanna Sörensen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2312-4917 49 ,

- Felipe Augusto Arguello Souza ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2753-9896 46 ,

- Kerstin Stahl ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2159-9441 19 ,

- Max Steinhausen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8692-8824 1 ,

- Michael Stoelzle ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0021-4351 19 ,

- Wiwiana Szalińska ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6828-6963 61 ,

- Qiuhong Tang 62 ,

- Fuqiang Tian ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9414-7019 63 ,

- Tamara Tokarczyk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5862-6338 61 ,

- Carolina Tovar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8256-9174 64 ,

- Thi Van Thu Tran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1187-3520 52 ,

- Marjolein H. J. Van Huijgevoort ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9781-6852 65 ,

- Michelle T. H. van Vliet ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2597-8422 66 ,

- Sergiy Vorogushyn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4639-7982 1 ,

- Thorsten Wagener ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3881-5849 21 , 50 , 67 ,

- Yueling Wang 62 ,

- Doris E. Wendt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2315-7871 67 ,

- Elliot Wickham 68 ,

- Long Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1872-0175 69 ,

- Mauricio Zambrano-Bigiarini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9536-643X 8 , 9 ,

- Günter Blöschl ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2227-8225 70 &

- Giuliano Di Baldassarre ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8180-4996 43 , 44 , 71

Nature volume 608 , pages 80–86 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

55k Accesses

145 Citations

971 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Natural hazards

Risk management has reduced vulnerability to floods and droughts globally 1 , 2 , yet their impacts are still increasing 3 . An improved understanding of the causes of changing impacts is therefore needed, but has been hampered by a lack of empirical data 4 , 5 . On the basis of a global dataset of 45 pairs of events that occurred within the same area, we show that risk management generally reduces the impacts of floods and droughts but faces difficulties in reducing the impacts of unprecedented events of a magnitude not previously experienced. If the second event was much more hazardous than the first, its impact was almost always higher. This is because management was not designed to deal with such extreme events: for example, they exceeded the design levels of levees and reservoirs. In two success stories, the impact of the second, more hazardous, event was lower, as a result of improved risk management governance and high investment in integrated management. The observed difficulty of managing unprecedented events is alarming, given that more extreme hydrological events are projected owing to climate change 3 .

Similar content being viewed by others

How the USA can benefit from risk-based premiums combined with flood protection

Biases in national and continental flood risk assessments by ignoring spatial dependence

Assessing the myth of disaster risk reduction in the wake of catastrophic floods

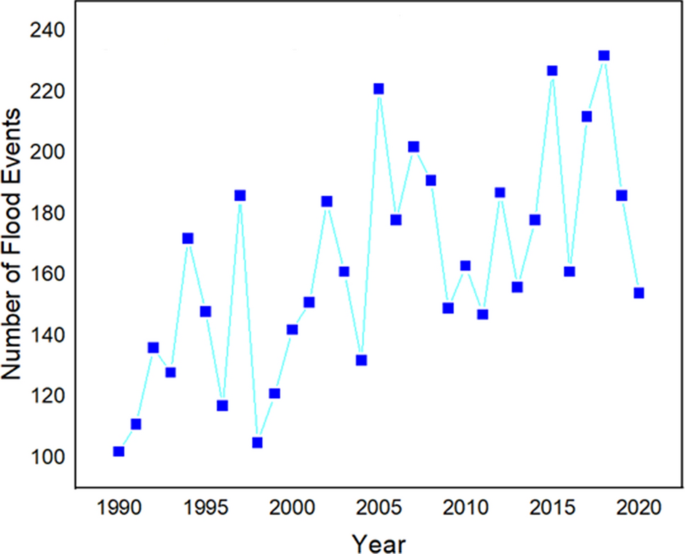

Observed decreasing trends in the vulnerability to floods and droughts, owing to effective risk management, are encouraging 1 . Globally, human and economic vulnerability dropped by approximately 6.5- and 5-fold, respectively, between the periods 1980–1989 and 2007–2016 (ref. 2 ). However, the impacts of floods and droughts are still severe and increasing in many parts of the world 6 . Climate change will probably lead to a further increase in their impacts owing to projected increases in the frequency and severity of floods and droughts 3 . The economic damage of floods is projected to double globally 7 and that of droughts to triple in Europe 8 , for a mean temperature increase of 2 °C.

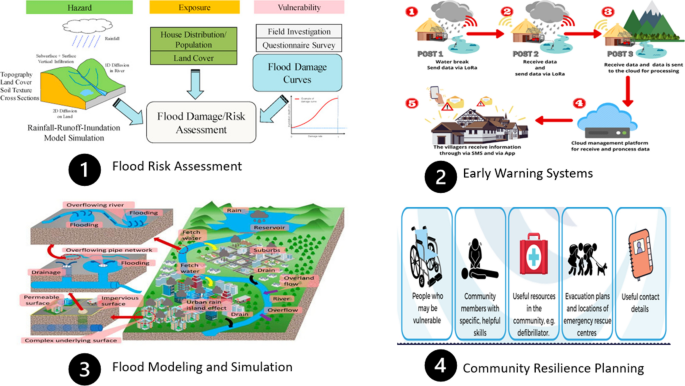

The purpose of risk management is to reduce the impact of events through modification of the hazard, exposure and/or vulnerability: according to United Nations (UN) terminology 9 , disaster risk management is the application of disaster risk reduction policies and strategies to prevent new disaster risk, reduce existing disaster risk and manage residual risk, contributing to the strengthening of resilience against, and reduction of, disaster losses. Hazard is a process, phenomenon or human activity that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation; exposure is the situation of people, infrastructure, housing, production capacities and other tangible human assets located in hazard-prone areas; and vulnerability is the conditions determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors or processes 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 that increase the susceptibility of an individual, a community, assets or systems to the impacts of hazards. To be effective, risk management needs to be based on a sound understanding of these controlling risk drivers 14 , 15 . Past studies have identified increasing exposure as a primary driver of increasing impacts 3 , 4 , and vulnerability reduction has been identified as key for reduction of impacts 16 , 17 . However, ascertaining the combined effect of the drivers and the overall effectiveness of risk management has been hampered by a lack of empirical data 4 , 5 .

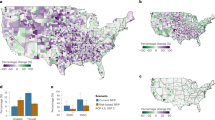

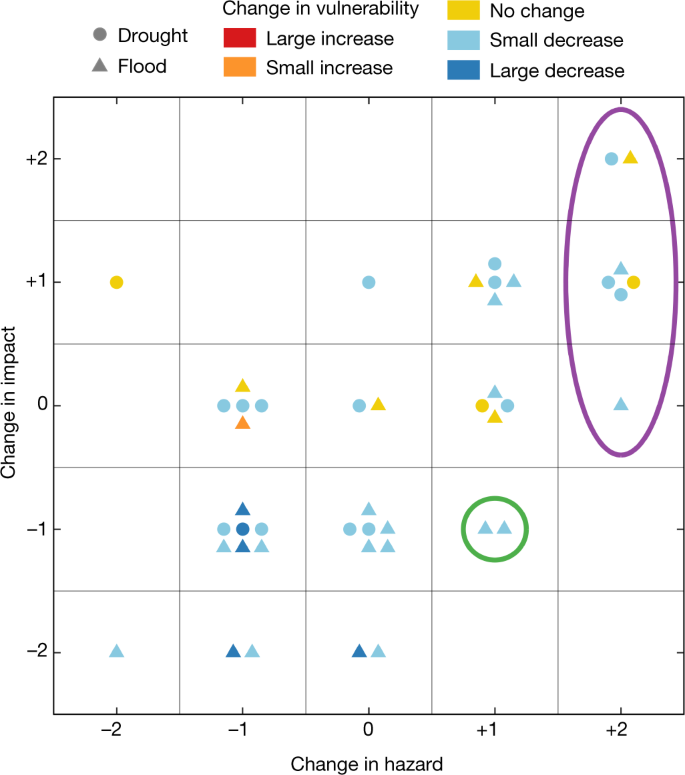

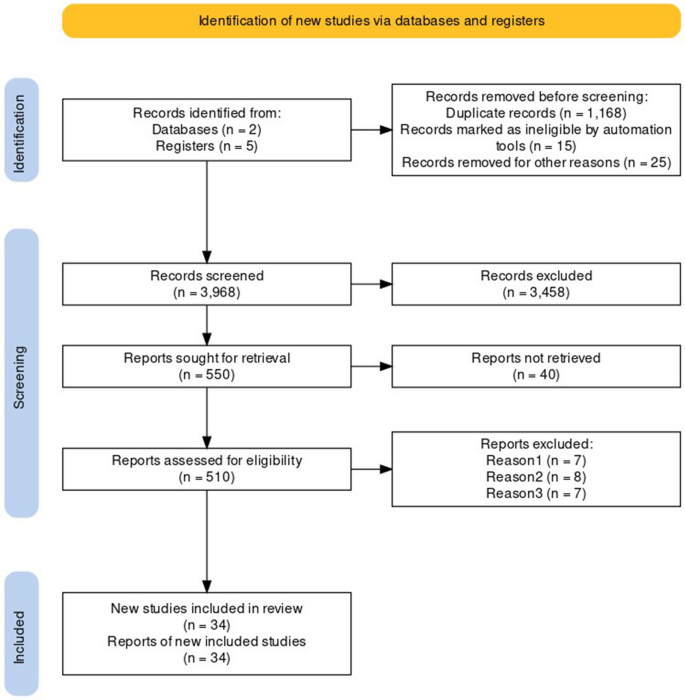

Here we analyse a new dataset of 45 pairs of flood or drought events that occurred in the same area on average 16 years apart (hereinafter referred to as paired events). The data comprise 26 flood and 19 drought paired events across different socioeconomic and hydroclimatic contexts from all continents (Fig. 1a ). We analyse floods and droughts together, because of the similarity of some of the management methods (for example, warning systems, water reservoir infrastructure), the potential for trade-offs in risk reduction between floods and droughts and therefore value for the management communities to learn from each other 18 . The impact, quantified by direct (fatalities, monetary damage), indirect (for example, disruption of traffic or tourism) and intangible impacts (for example, impact on human health or cultural heritage), is considered to be controlled by three drivers: hazard, exposure and vulnerability 3 . These drivers are quantified using a large range of different indices—for example, the standardized precipitation index, the number of houses in the affected area and risk awareness, respectively (Supplementary Table 1 ). These three drivers are considered to be exacerbated by management shortcomings. Hazard may be exacerbated by problems with water management infrastructure such as levees or reservoirs 19 . Exposure and vulnerability may be worsened by suboptimal implementation of non-structural measures such as risk-aware regional planning 20 or early warning 21 , respectively. We analyse management shortcomings and their effect on the three drivers explicitly, as this is the point at which improvements can start—for example, by the introduction of better strategies and policies. Data availability understandably varies among the paired events, and this can introduce inconsistency and subjectivity. The analyses are therefore based on indicators of change, to account for differences between paired events in respect of measured variables, data quality and uncertainty. These indicators of change represent the differences between the first event (baseline) and the second, categorized as large decreases/increases (−2/+2), small decreases/increases (−1/+1) and no change (0) (Supplementary Table 2 ). To minimize the subjectivity and uncertainty of indicator assignment, a quality assurance protocol is implemented and indicators of change with sub-indicators are used.

a , Location of flood and drought paired events ( n = 45). Numbers are paired-event IDs. b , Indicators of change, sorted by impact change. Impact is considered to be controlled by hazard, exposure and vulnerability, which are exacerbated by risk management shortcomings. Maps of the paired events coloured according to drivers and management shortcomings are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 .

Source data

The majority of paired events show decreases in management shortcomings (71% of paired events; Fig. 1b ), which reflects that societies tend to learn from extreme events 22 . Most cases also show a decrease in vulnerability (80% of paired events) as societies typically reduce their vulnerability after the first event of a pair 21 . The five paired events with a large decrease in impact (dark blue, top left in Fig. 1b ) are associated with decreases or no change of all three drivers.

Drivers of changes in impact

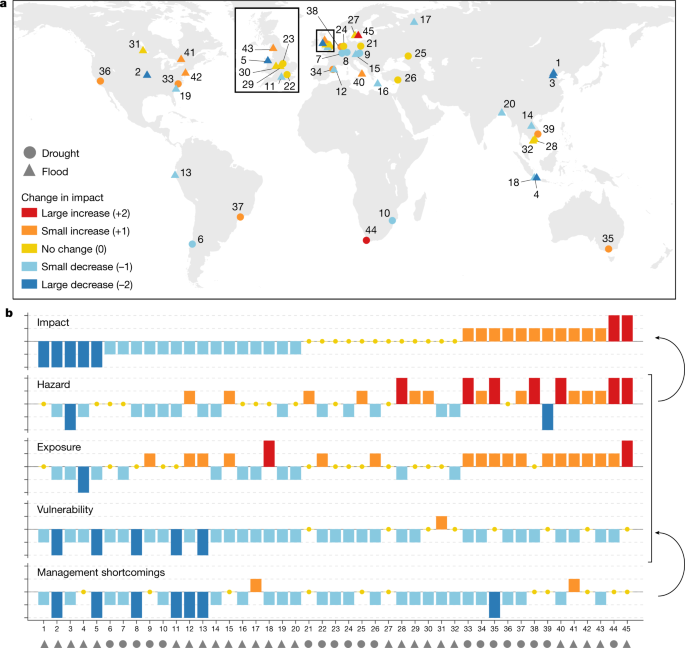

Changes in flood impacts are significantly and positively correlated with changes in hazard ( r = 0.64, P ≤ 0.01), exposure ( r = 0.55, P ≤ 0.01) and vulnerability ( r = 0.60, P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 2a ), which is in line with risk theory 3 . Although a previous analysis of eight case studies 21 identified vulnerability as a key to reduction of flood impacts, this new, more comprehensive, dataset suggests that changes in hazard, exposure and vulnerability are equally important, given that they correlate equally strongly with changes in flood impact. Changes in drought impacts are significantly correlated with changes in hazard and exposure, but not with changes in vulnerability (Fig. 2c ). This suggests that changes in vulnerability have been less successful in reducing drought impact than flood impact, which is also consistent with those event pairs for which only vulnerability changed (Extended Data Table 1 ). However, quantification of the contribution of individual drivers is difficult with this empirical approach because there are only a limited number of cases in which only one driver changed. There are three cases in which only vulnerability changed between events, two cases in which only hazard changed and no case in which only exposure changed (Extended Data Table 1 ). Additionally, paired events without a change in hazard (0) are analysed in more detail to better understand the role of exposure and vulnerability (Extended Data Fig. 2 ). In all these paired events, a reduction in impact was associated with a reduction in vulnerability, highlighting the importance of vulnerability. In five of these eight cases with a decrease in impact there was also a decrease in exposure, whereas in one case (floods in Jakarta, Indonesia in 2002 and 2007 (ID 18)) there was a large increase in exposure. In the paired event of droughts in California, United States (1987–1992 and 2011–2016, ID 36) an increase in exposure and a reduction in vulnerability increased impact, which points to the more important role of exposure in comparison with vulnerability in this drought case (Extended Data Fig. 2 ).

a , c , Correlation matrix of indicators of change for flood ( a ) and drought ( c ) paired events. Colours of squares indicate Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients and their size, the P value. b , d ,Histograms of indicators of change of flood ( b ) and drought ( d ) stratified by decrease ( n = 15 and n = 5 paired events for flood and drought, respectively) and increase ( n = 5 and n = 8 paired events, respectively) in impact. The asterisk denotes the success stories of Box 1 ; double asterisks denote pairs for which the second event was much more hazardous than the first (that is, 'unprecedented'). Mgmt shortc, management shortcomings.

Generally the changes in drivers are not significantly correlated with each other, with the exception of hazard and exposure in the case of floods ( r = 0.55, P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 2a ). This finding may be explained by the influence of hazard on the size of the inundation area, and thus on the numbers of people and assets affected, which represent exposure.

The sensitivity analysis suggests that the correlation pattern is robust, as visualized by the colours in Extended Data Fig. 3 . The pattern of P values is also robust for flood cases, although these become less significant for drought because of the smaller sample size (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

We split the paired events into groups of decreasing and increasing impact to evaluate their drivers separately (Fig. 2b,d ). Overall, the pattern is similar for floods and droughts. Most flood and drought pairs with decreasing impact show either a decrease in hazard (ten pairs, 50%) or no change (eight pairs, 40%). Exceptions are two flood pairs that are success stories of decreased impact despite an increase in hazard, as detailed in Box 1 . The change in exposure of the pairs with decreased impacts (Fig. 2b,d ) ranges from a large decrease to a large increase, whereas vulnerability always decreased. All cases with a large decrease in vulnerability (−2) are associated with a decrease in impacts. Overall, the pattern suggests that a decrease in impacts is mainly caused by a combination of lower hazard and vulnerability, despite an increase in exposure in 25% of cases.

The role of hazard and vulnerability in impact reduction can be exemplified by the pair of riverine floods in Jakarta, Indonesia (ID 4 in Fig. 1 ). The 2007 event had a flood return period of 50 years, whereas it was 30 years for the 2013 event 23 (that is, the hazard of the second event was smaller). Vulnerability had also decreased as a result of improved preparedness resulting from a flood risk mapping initiative and capacity building programmes implemented after the first flood, to improve citizens' emergency response, as well as by an improvement in official emergency management by establishment of the National Disaster Management Agency in 2008. Additionally, exposure was substantially reduced. Whilst the first flood caused 79 fatalities and direct damage of €1.3 billion, the second event caused 38 fatalities and €0.76 billion of direct damage.

Another example is a pair of Central European droughts (ID 9). During the 2003 event, the minimum 3-month Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index was −1.62 whereas in 2015 it was −1.18—that is, the hazard of the second event was smaller 24 . The vulnerability was also lower in the second event, because the first event had raised public awareness and triggered an improvement in institutional planning. For instance, the European Commission technical guidance on drought management plans 25 was implemented. Many reservoirs were kept filled until the beginning of summer 2015, which alleviated water shortages for various sectors and, in some cities (for example, Bratislava and Bucharest), water was supplied from tanks 26 . Additionally, water use and abstraction restrictions were implemented for non-priority uses including irrigation 26 . The impact was reduced from €17.1 billion to €2.2 billion, despite an increase in exposure because of the larger drought extent affecting almost all of Europe in 2013.

Most flood and drought pairs with an increase in impact also show a larger hazard (11 cases, 85%; Fig. 2b,d ). For six of these paired events (46%), the second event was much more hazardous than the first (hazard indicator-of-change +2), whereas this was never the case for the pairs with decreasing impact. Of those pairs with an increase in impact, 12 (92%) show an increase in exposure and nine (69%) show a small decrease in vulnerability (vulnerability indicator-of-change −1). Overall, the pattern suggests that the increase in impact is mainly caused by a combination of higher hazard and exposure, which is not compensated by a small decrease in vulnerability.

The role of hazard and exposure in increasing impact is illustrated by a pair of pluvial floods in Corigliano-Rossano City, Calabria, Italy (ID 40). This 2015 event was much more hazardous (+2) than that in 2000, with precipitation return periods of more than 100 and 10–20 years, respectively 27 . Also, the 2000 event occurred during the off-season for tourism in September whereas the exposure was much larger in 2015, because the event occurred in August when many tourists were present. Interruption of the peak holiday season caused severe indirect economic damage. Another example is a pair of droughts (ID 33) affecting North Carolina, United States. Between 2007 and 2009, about 65% of the state was affected by what was classified as an exceptional drought, with a composite drought indicator of the US Drought Monitor of 27 months 28 , whereas between 2000 and 2003 only about 30% of the state was affected by an exceptional drought of 24 months 28 . The crop losses in 2007–2009 were about €535 million, whereas they were €497 million in 2000–2003, even though vulnerability had been reduced due to drought early warning and management by the North Carolina Drought Management Council, established in 2003.

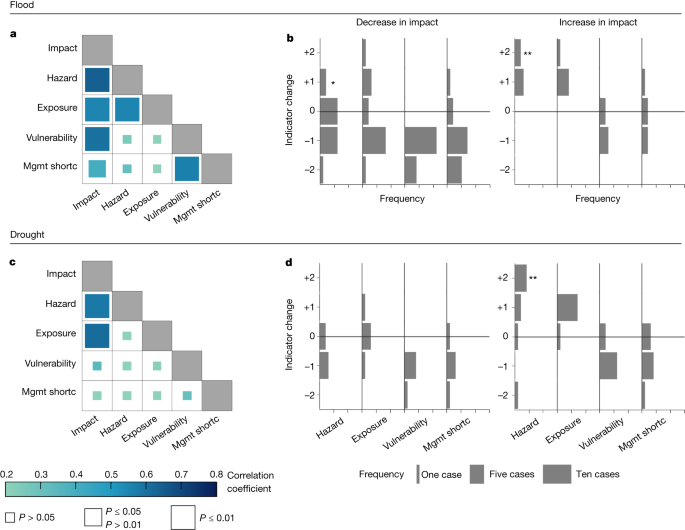

Box 1 Success stories of decreased impact despite increased hazard

The dataset includes two cases in which a lower impact was achieved despite a larger hazard of the second event, making these interesting success stories (Fig. 3 ). Both cases are flood paired events, but of different types (that is, pluvial and riverine floods (Table 1 )). These cases have in common that institutional changes and improved flood risk management governance were introduced and high investments in integrated management were undertaken, which led to an effective implementation of structural and non-structural measures, such as improved early warning and emergency response to complement structural measures such as levees (Table 1 ).

Effects of changes in management on drivers

The correlations shown in Fig. 2a,c also shed light on how management affects hazard, exposure and vulnerability and thus, indirectly, impact. For flood paired events, changes in management shortcomings are significantly positively correlated with changes in vulnerability ( r = 0.56, P ≤ 0.01), and both are significantly positively correlated with changes in impact (Fig. 2a ). For drought, however, these correlations are not significant (Fig. 2c ). Thus, achieving decreases in vulnerability, and consequently in impact, by improving risk management (that is, reducing management shortcomings) seems to be more difficult for droughts than for floods. This difficulty may be related to spillover effects—that is, drought measures designed to reduce impacts in one sector can increase impacts in another. For example, irrigation to alleviate drought in agriculture may increase drought impacts on drinking water supply and ecology 29 .

The paired floods in the Piura region, Peru (ID 13) illustrate how effective management can reduce vulnerability, and consequently impact. At the Piura river, maximum flows of 3,367 and 2,755 m 3 s −1 were recorded during the 1998 and 2017 events, respectively (that is, hazard showed a small decrease (−1)). Around 2000, the national hydrometeorological service started to issue medium-range weather forecasts that allowed preparations months before the 2017 event. In 2011, the National Institute of Civil Defence and the National Centre for the Estimation, Prevention, and Reduction of Disaster Risk were founded which, together with newly established short-range river flow forecasts, allowed more efficient emergency management of the more recent event. Additionally, non-governmental organizations such as Practical Action had implemented disaster risk-reduction activities, including evacuation exercises and awareness campaigns 30 . All of these improvements in management decreased vulnerability. The impact of the second event was smaller, with 366 fatalities in 1998 compared with 159 in 2017, despite an increase in exposure due to urbanization and population increase.

When the hazard of the second event was larger than that of the first (+1, +2), in 11 out of 18 cases (61%) the impact of the second event was also larger, irrespective of small decreases in vulnerability in eight of these cases (light blue dots/triangles in Fig. 3 ). There are only two paired events in our dataset for which a decrease in impact was achieved despite the second event being more hazardous (highlighted by the green circle in Fig. 3 ). These cases are considered success stories and are further discussed in Box 1 . For the two paired events (ID 21 and 30) for which the only driver that changed was hazard (+1), the impacts did not change (0) (Extended Data Table 1 ). Water retention capacity of 189,881,000 m³ and good irrigation infrastructure with sprinkling machines were apparently sufficient to counteract the slight increase in hazard for the drought paired event in Poland in 2006 and 2015 (ID 21). The improved flood alleviation scheme implemented between the paired flood events (2016 and 2018), protected properties in Birmingham, United Kingdom (ID 30). There are, however, seven cases for which the second event was much more hazardous (+2) than the first (highlighted by the purple ellipse in Fig. 3 )—that is, events of a magnitude that locals had probably not previously experienced. We term these events, subjectively, as unprecedented; almost all had an increased impact despite improvements in management.

Categories are: lower hazard and lower impact, ten cases; higher hazard and higher impact, 11 cases; lower hazard and higher impact, one case; higher hazard and lower impact, two cases. Circles and triangles indicate drought and flood paired events, respectively; their colours indicate change in vulnerability. Green circle highlights success stories ( n = 2) of reduced impact (−1) despite a small increase in hazard (+1). Purple ellipse indicates paired events ( n = 7) with large increase in hazard (+2)—that is, events that were subjectively unprecedented and probably not previously experienced by local residents.

One unprecedented pluvial flood is the 2014 event in the city of Malmö, Sweden (ID 45). This event was much more hazardous than that experienced a few years before, with precipitation return periods on average of 135 and 24 years, respectively, for 6 h duration 31 . The largest 6 h precipitation measured at one of nine stations during the 2014 event corresponded to a return period of 300 years. The combined sewage system present in the more densely populated areas of the city was overwhelmed, leading to extensive basement flooding in 2014 (ref. 31 ). The direct monetary damage was about €66 million as opposed to €6 million in the first event. An unprecedented drought occurred in the Cape Town metropolitan area of South Africa, in 2015–2018 (ID 44). The drought was much longer (4 years) than that experienced previously in 2003–2004 (2 years). Although the Berg River Dam had been added to the city’s water supply system in 2009, and local authorities had developed various strategies for managing water demands (for example, water restrictions, tariff increases, communication campaign), the second event caused a much higher direct impact of about €180 million 32 because the water reserves were reduced to virtually zero.

Even though it is known that vulnerability reduction plays a key role in reducing risk, our paired-event cases reveal that when the hazard of the second event was higher than the first, a reduction in vulnerability alone was often not sufficient to reduce the impact of the second event to less than that of the first. Our analysis of drivers of impact change reveals the importance of reducing hazard, exposure and vulnerability to achieve an effective impact reduction (Fig. 2 ). Although previous studies have attributed a high priority to vulnerability reduction 17 , 21 , the importance of considering all three drivers identified here may reflect the sometimes limited efficiency of management decisions, resulting in unintended consequences. For example, levee construction aiming at reducing hazards may increase exposure through encouraging settlements in floodplains 33 , 34 . Similarly, construction of reservoirs to abate droughts may enhance exposure through encouraging agricultural development and thus increase water demand 35 , 36 .

Events that are much more hazardous than preceding events (termed unprecedented here) seem to be difficult to manage; in almost all the cases considered they led to increased impact (Fig. 3 ). This finding may be related to two factors. First, large infrastructure such as levees and water reservoirs play an important role in risk management. These structures usually have an upper design limit up to which they are effective but, once a threshold is exceeded, they become ineffective. For example, the unprecedented pluvial flood in 2014 in Malmö, Sweden (ID 45) exceeded the capacity of the sewer system 31 and the unprecedented drought in Cape Town (ID 44) exceeded the storage water capacity 37 . This means that infrastructure is effective in preventing damage during events of a previously experienced magnitude, but often fails for unprecedented events. Non-structural measures, such as risk-aware land-use planning, precautionary measures and early warning, can help mitigate the consequences of water infrastructure failure in such situations 21 , but a residual risk will always remain. Second, risk management is usually implemented after large floods and droughts, whereas proactive strategies are rare. Part of the reason for this behaviour is a cognitive bias associated with the rarity and uniqueness of extremes, and the nature of human risk perception, which makes people attach a large subjective probability to those events they have personally experienced 38 .

On the other hand, two case studies were identified in which impact was reduced despite an increase in hazard (Box 1 ). An analysis of these case studies identifies three success factors: (1) effective governance of risk and emergency management, including transnational collaboration such as in the Danube case; (2) high investments in structural and non-structural measures; and (3) improved early warning and real-time control systems such as in the Barcelona case. We believe there is potential for more universal application of these success factors to counteract the current trend of increasing impacts associated with climate change 3 . These factors may also be effective in the management of unprecedented events, provided they are implemented proactively.

The concept of paired events aims at comparing two events of the same hazard type that occurred in the same area 21 to learn from the differences and similarities. This concept is analogous to paired catchment studies, which compare two neighbouring catchments with different vegetation in terms of their water yield 39 . Our study follows the theoretical risk framework that considers impact as a result of three risk components or drivers 3 : hazard, exposure and vulnerability (Extended Data Fig. 4 ). Hazard reflects the intensity of an event, such as a flooded area or drought deficit—for example, measured by the standardized precipitation index. Exposure reflects the number of people and assets in the area affected by the event. Consequently, the change in exposure between events is influenced by changes in the population density and the assets in the affected area (socioeconomic developments), as well as by changes in the size of the affected area (change of hazard). Vulnerability is a complex concept, with an extensive literature from different disciplines on how to define, measure and quantify it 13 , 40 , 41 , 42 . For instance, Weichselgartner 43 lists more than 20 definitions of vulnerability, and frameworks differ quite substantially—for example, in terms of integration of exposure into vulnerability 11 or separating them 3 . Reviews and attempts to converge on the various vulnerability concepts stress that vulnerability is dynamic and that assessments should be conducted for defined human–environment systems at particular places 12 , 44 , 45 . Every vulnerability analysis requires an approach adapted to its specific objectives and scales 46 . The paired event approach allows detailed context and place-based vulnerability assessments that are presented in the paired event reports, as well as comparisons across paired events based on the indicators-of-change. The selection of sub-indicators for the characterization of vulnerability is undertaken with a particular focus on temporal changes at the same place. All three drivers—hazard, exposure and vulnerability—can be reduced by risk-management measures. Hazard can be reduced by structural measures such as levees or reservoirs 19 , exposure by risk-aware regional planning 20 and vulnerability by non-structural measures, such as early warning 21 .

Our comparative analysis is based on a novel dataset of 45 paired events from around the world, of which 26 event pairs are floods and 19 are droughts. The events occurred between 1947 and 2019, and the average period between the two events of a pair is 16 years. The number of paired events is sufficiently large to cover a broad range of hydroclimatic and socioeconomic settings around the world and allows differentiated, context-specific assessments on the basis of detailed in situ observations. Flood events include riverine, pluvial, groundwater and coastal floods 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 . Drought events include meteorological, soil moisture and hydrological (streamflow, groundwater) droughts 51 . The rationale for analysing floods and droughts together is based on their position at the two extremes of the same hydrological cycle, the similarity of some management strategies (for example, warning systems, water reservoir infrastructure), potential trade-offs in the operation of the same infrastructure 52 and more general interactions between these two risks (for example, water supply to illegal settlements that may spur development and therefore flood risk). There may therefore be value in management communities learning from each other 18 .

The dataset comprises: (1) detailed review-style reports about the events and key processes between the events, such as changes in risk management (open access data; Data Availability statement); (2) a key data table that contains the data (qualitative and quantitative) characterizing the indicators for the paired events, extracted from individual reports (open access data); and (3) an overview table providing indicators-of-change between the first and second events (Supplementary Table 3 ). To minimize the elements of subjectivity and uncertainty in the analysis, we (1) used indicators-of-change as opposed to indicators of absolute values, (2) calculated indicators from a set of sub-indicators (Supplementary Table 1 ) and (3) implemented a quality assurance protocol. Commonly, more than one variable was assessed per sub-indicator (for example, flood discharges at more than one stream gauge, or extreme rainfall at several meteorological stations). A combination or selection of the variables was used based on hydrological reasoning on the most relevant piece of information. Special attention was paid to this step during the quality assurance process, drawing on the in-depth expertise on events of one or more of our co-authors. The assignment of values for the indicators-of-change, including quality assurance, was inspired by the Delphi Method 53 that is built on structured discussion and consensus building among experts. The process was driven by a core group (H.K., A.F.V.L., K. Schröter, P.J.W. and G.D.B.) and was undertaken in the following steps: (1) on the basis of the detailed report, a core group member suggested values for all indicators-of-change for a paired event; (2) a second member of the core group reviewed these suggestions; in case of doubt, both core group members rechecked the paired event report and provided a joint suggestion; (3) all suggestions for the indicators-of-change for all paired events were discussed in the core group to improve consistency across paired events; (4) the suggested values of the indicators-of-change were reviewed by the authors of the paired-event report; and finally (5), the complete table of indicators-of-change (Supplementary Table 3 ) was reviewed by all authors to ensure consistency between paired events. Compound events were given special consideration, and the best possible attempt was made to isolate the direct effects of floods and droughts from those of concurrent phenomena on hazard, exposure and impact, based on expert knowledge of the events of one or more of the co-authors. For instance, in the course of this iterative process it became clear that fatalities during drought events were not caused by a lack of water, but by the concurrent heatwave. It was thus decided to omit the sub-indicator ‘fatalities’ in drought impact characterization. The potential biases introduced by compound events were further reduced by the use of the relative indicators-of-change between similar event types with similar importance of concurrent phenomena.

The indicator-of-change of impact is composed of the following sub-indicators: number of fatalities (for floods only), direct economic impact, indirect impact and intangible impact (Supplementary Table 1 ). Flood hazard is composed of the sub-indicators precipitation/weather severity, severity of flood, antecedent conditions (for pluvial and riverine floods only), as well as the following for coastal floods only: tidal level and storm surge. Drought hazard is composed of the duration and severity of drought. Exposure is composed of the two sub-indicators people/area/assets exposed and exposure hotspots. Vulnerability is composed of the four sub-indicators lack of awareness and precaution, lack of preparedness, imperfect official emergency/crisis management and imperfect coping capacity. Indicators-of-change, including sub-indicators, were designed such that consistently positive correlations with impact changes are expected (Supplementary Table 1 ). For instance, a decrease in 'lack of awareness' leads to a decrease in vulnerability and is thus expected to be positively correlated with a decrease in impacts. Management shortcomings are characterized by problems with water management infrastructure and non-structural risk management shortcomings, which means that non-structural measures were not optimally implemented. These sub-indicators were aggregated into indicators-of-change for impact, hazard, exposure, vulnerability and management shortcomings, to enable a consistent comparison between flood and drought paired events. This set of indicators is intended to be as complementary as possible, but overlaps are hard to avoid because of interactions between physical and socioeconomic processes that control flood and drought risk. Although the management shortcoming indicator is primarily related to the planned functioning of risk management measures, and hazard, exposure and vulnerability primarily reflect the concrete effects of measures during specific events, there is some overlap between the management shortcoming indicator and all three drivers. Supplementary Table 1 provides definitions and examples of description or measurement of sub-indicators for flood and drought paired events.

The changes are indicated by −2/2 for large decrease or increase, −1/1 for small decrease or increase and 0 for no change. In the case of quantitative comparisons (for example, precipitation intensities and monetary damage), a change of less than around 50% is usually treated as a small change and above approximately 50% as a large change, but always considering the specific measure and paired events. Supplementary Table 2 provides representative examples from flood and drought paired events showing how differences in quantitative variables and qualitative information between the two events of a pair correspond to the values of the sub-indicators, ranging from large decrease (−2) to large increase (+2). We assume that an event is unprecedented in a subjective way—that is, it has probably not been experienced before—if the second event of a pair is much more hazardous than the first (hazard indicator-of-change +2).

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients are calculated for impact, drivers and management shortcomings, separated for flood and drought paired events. Despite the measures taken to minimize the subjectivity and uncertainty of indicator assignment, there will always be an element of subjectivity. To address this, we carried out a Monte Carlo analysis (1,000 iterations) to test the sensitivity of the results when randomly selecting 80% of flood and drought paired events. For each subsample correlation, coefficients and P values were calculated to obtain a total of 1,000 correlation and 1,000 P value matrices. The 25th and 75th quantiles of the correlation coefficients and P values were calculated separately (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Data availability

The dataset containing the individual paired event reports, the key data table and Supplementary Tables 1 – 3 are openly available via GFZ Data Services ( https://doi.org/10.5880/GFZ.4.4.2022.002 ). Source data are provided with this paper.

Jongman, B. et al. Declining vulnerability to river floods and the global benefits of adaptation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , E2271–E2280 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Formetta, G. & Feyen, L. Empirical evidence of declining global vulnerability to climate-related hazards. Glob. Environ. Change 57 , 101920 (2019).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

IPCC. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation (eds Field, C.B. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Bouwer, L. M. Have disaster losses increased due to anthropogenic climate change? Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 92 , 39–46 (2011).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Ward, P. J. et al. Natural hazard risk assessments at the global scale. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20 , 1069–1096 (2020).

Economic Losses, Poverty & Disasters (1998–2017) (UNISDR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction) and CRED (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters), 2018); https://www.cred.be/unisdr-and-cred-report-economic-losses-poverty-disasters-1998-2017

Dottori, F. et al. Increased human and economic losses from river flooding with anthropogenic warming. Nat. Clim. Change 8 , 781–786 (2018).

Cammalleri, C. et al. Global Warming and Drought Impacts in the EU (Publications Office of the European Union, 2020); https://doi.org/10.2760/597045

Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction), 2017); www.undrr.org/terminology

Cutter, S. L., Boruff, B. J. & Shirley, W. L. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 84 , 242–261 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Turner, B. L. et al. A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100 , 8074–8079 (2003).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Eakin, H. & Luers, A. L. Assessing the vulnerability of social-environmental systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 31 , 365–394 (2006).

Eriksen, S. et al. Adaptation interventions and their effect on vulnerability in developing countries: help, hindrance or irrelevance? World Dev. Rev. 141 , 105383 (2020).

Kreibich, H. et al. Costing natural hazards. Nat. Clim. Change 4 , 303–306 (2014).

De Ruiter, M. C. et al. Why we can no longer ignore consecutive disasters. Earths Future 8 , e2019EF001425 (2020).

Di Baldassarre, G. A. et al. Perspectives on socio-hydrology: capturing feedbacks between physical and social processes. Water Resour. Res. 51 , 4770–4781 (2015).

Mechler, R. & Bouwer, L. M. Understanding trends and projections of disaster losses and climate change: is vulnerability the missing link? Clim. Change 133 , 23–35 (2015).

Ward, P. J. et al. The need to integrate flood and drought disaster risk reduction strategies. Water Secur. 11 , 100070 (2020).

Raikes, J. et al. Pre-disaster planning and preparedness for floods and droughts: a systematic review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 38 , 101207 (2019).

Johnson, K. A. et al. A benefit–cost analysis of floodplain land acquisition for US flood damage reduction. Nat. Sustain. 3 , 56–62 (2019).

Kreibich, H. et al. Adaptation to flood risk: results of international paired flood event studies. Earths Future 5 , 953–965 (2017).

Birkland, T. A. Focusing events, mobilization, and agenda setting. J. Public Policy 18 , 53–74 (1998).

Budiyono, Y. et al. River flood risk in Jakarta under scenarios of future change. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 16 , 757–774 (2016).

Ionita, M. et al. The European 2015 drought from a climatological perspective. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21 , 1397–1419 (2017).

Drought Management Plan Report (European Commission, 2007); https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/quantity/pdf/dmp_report.pdf

Van Lanen, H. A. J. et al. Hydrology needed to manage droughts: the 2015 European case. Hydrol. Process. 30 , 3097–3104 (2016).

Petrucci, O. et al. Civil protection and damaging hydrogeological events: comparative analysis of the 2000 and 2015 events in Calabria (southern Italy). Adv. Geosci. 44 , 101–113 (2017).

NDMC (National Drought Mitigation Center) U.S. Drought Monitor https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu (2020).

Garrick, D. E. et al. Managing the cascading risks of droughts: institutional adaptation in transboundary river basins. Earths Future 6 , 809–827 (2018).

French, A. & Mechler, R. Managing El Niño Risks Under Uncertainty in Peru (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 2017); http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/14849/1/French_Mechler_2017_El%20Ni%C3%B1o_Risk_Peru_Report.pdf

Sörensen, J. & Mobini, S. Pluvial, urban flood mechanisms and characteristics—assessment based on insurance claims. J. Hydrol. 555 , 51–67 (2017).

Muller, M. Cape Town’s drought: don’t blame climate change. Nature 559 , 174–176 (2018).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

White, G. F. Human Adjustment to Floods (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1945).

Wenger, C. Better use and management of levees: reducing flood risk in a changing climate. Environ. Rev. 23 , 240–255 (2015).

Kallis, G. Coevolution in water resource development: the vicious cycle of water supply and demand in Athens, Greece. Ecol. Econ. 69 , 796–809 (2010).

Di Baldassarre, G. et al. Water shortages worsened by reservoir effects. Nat. Sustain. 1 , 617–622 (2018).

Savelli, E. et al. Don’t blame the rain: social power and the 2015–2017 drought in Cape Town. J. Hydrol. 594 , 125953 (2021).

Merz, B. et al. Charting unknown waters—on the role of surprise in flood risk assessment and management. Water Resour.Res. 51 , 6399–6416 (2015).

Brown, A. E. et al. A review of paired catchment studies for determining changes in water yield resulting from alterations in vegetation. J. Hydrol. 310 , 28–61 (2005).

Cutter, S. L. & Finch, C. Temporal and spatial changes in social vulnerability to natural hazards. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 2301–2306 (2008).

Hinkel, J. ‘‘Indicators of vulnerability and adaptive capacity’’: towards a clarification of the science–policy interface. Glob. Environ. Change 21 , 198–208 (2011).

Tate, E. Social vulnerability indices: a comparative assessment using uncertainty and sensitivity analysis. Nat. Hazards 63 , 325–347 (2012).

Weichselgartner, J. Disaster mitigation: the concept of vulnerability revisited. Disaster Prev. Manage. 10 , 85–94 (2001).

Adger, W. N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 16 , 268–281 (2006).

Birkmann, J. Framing vulnerability, risk and societal responses: the MOVE framework. Nat. Hazards 67 , 193–211 (2013).

Thywissen, K. Components of Risk—a Comparative Glossary (UNU-EHS, 2006); http://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:1869

Tarasova, L. et al. Causative classification of river flood events. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 6 , e1353 (2019).

Google Scholar

Rosenzweig, B. R. et al. Pluvial flood risk and opportunities for resilience. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 5 , e1302 (2018).

Ascott, M. J. et al. Improved understanding of spatio‐temporal controls on regional scale groundwater flooding using hydrograph analysis and impulse response functions. Hydrol. Proc. 31 , 4586–4599 (2017).

Danard, M., Munro, A. & Murty, T. Storm surge hazard in Canada. Nat. Hazards 28 , 407–431 (2003).

Tallaksen, L. & Lanen, H. A. J. V. Hydrological Drought. Processes and Estimation Methods for Streamflow and Groundwater (Elsevier, 2004).

Van den Honert, R. C. & McAneney, J. The 2011 Brisbane floods: causes, impacts and implications. Water 3 , 1149–1173 (2011).

Okoli, C. & Pawlowski, S. D. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inform. Manage. 42 , 15–29 (2004).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The presented work was developed by the Panta Rhei Working Groups 'Changes in flood risk' and 'Drought in the Anthropocene' within the framework of the Panta Rhei Research Initiative of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences. We thank the Barcelona Cicle de l’Aigua S.A., Barcelona City Council, Environment Agency (United Kingdom), Länsförsäkringar Skåne, Steering Centre for Urban Flood Control Programme in HCMC (Vietnam), VA SYD and the West Berkshire Council (United Kingdom) for data. The work was partly undertaken under the framework of the following projects: Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Professorship endowed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF); British Geological Survey’s Groundwater Resources Topic (core science funding); C3-RiskMed (no. PID2020-113638RB-C22), financed by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain; Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (no. ANID/FONDAP/15110009); CNES, through the TOSCA GRANT SWHYM; DECIDER (BMBF, no. 01LZ1703G); Deltares research programme on water resources; Dutch Research Council VIDI grant (no. 016.161.324); FLOOD (no. BMBF 01LP1903E), as part of the ClimXtreme Research Network. Funding was provided by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate; Global Water Futures programme of University of Saskatchewan; GlobalHydroPressure (Water JPI); HUMID project (no. CGL2017-85687-R, AEI/FEDER, UE); HydroSocialExtremes (ERC Consolidator Grant no. 771678); MYRIAD-EU (European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 101003276); PerfectSTORM (no. ERC-2020-StG 948601); Project EFA210/16 PIRAGUA, co-founded by ERDF through the POCTEFA 2014–2020 programme of the European Union; Research project nos. ANID/FSEQ210001 and ANID/NSFC190018, funded by the National Research and Development Agency of Chile; SECurITY (Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 787419); SPATE (FWF project I 4776-N, DFG research group FOR 2416); the UK Natural Environment Research Council-funded project Land Management in Lowland Catchments for Integrated Flood Risk Reduction (LANDWISE, grant no. NE/R004668/1); UK NERC grant no. NE/S013210/1 (RAHU) (W.B.); Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development under grant no. 105.06-2019.20.; and Vietnam National University–HCMC under grant no. C2018-48-01. D.M. and A. McKenzie publish with the permission of the Director, British Geological Survey. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not the organizations for which they work.

Open access funding provided by Helmholtz-Zentrum Potsdam Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum - GFZ.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Section Hydrology, Potsdam, Germany

Heidi Kreibich, Kai Schröter, Nivedita Sairam, Max Steinhausen & Sergiy Vorogushyn

Institute for Environmental Studies, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Anne F. Van Loon, Philip J. Ward, Maurizio Mazzoleni, Marlies H. Barendrecht, Anaïs Couasnon & Marleen C. de Ruiter

Leichtweiss Institute for Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources, Division of Hydrology and River basin management, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany

Kai Schröter

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

Guta Wakbulcho Abeshu & Hong-Yi Li

Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia

Svetlana Agafonova, Natalia Frolova, Maxim Kharlamov, Maria Kireeva & Alexey Sazonov

University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

Amir AghaKouchak & Laurie S. Huning

Department of Civil Engineering, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey

Hafzullah Aksoy

Center for Climate and Resilience Research, Santiago, Chile

Camila Alvarez-Garreton & Mauricio Zambrano-Bigiarini

Department of Civil Engineering, Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile

Operations Department, Barcelona Cicle de l’Aigua S.A, Barcelona, Spain

Blanca Aznar & Jordi Oriol Grima

Global Institute for Water Security, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Laila Balkhi, Hayley Carlson & Saman Razavi

LEGOS, Université de Toulouse, CNES, CNRS, IRD, UPS, Toulouse, France

Sylvain Biancamaria

Department of Groundwater Management, Deltares, Delft, the Netherlands

Liduin Bos-Burgering

School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Chris Bradley & Lucinda Capewell

Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology, Jakarta, Indonesia

Yus Budiyono

Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Imperial College London, London, UK

Wouter Buytaert

Department of Civil Engineering, Beykent University, Istanbul, Turkey

Yonca Cavus

Graduate School, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey

Faculty of Environment and Natural Resources, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

Yonca Cavus, Mathilde Erfurt, Kerstin Stahl & Michael Stoelzle

Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Gemma Coxon & Jim Freer

Cabot Institute, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Gemma Coxon, Jim Freer & Thorsten Wagener

Department of Agriculture, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklio, Greece

Ioannis Daliakopoulos

Université de Lorraine, LOTERR, Metz, France

Claire Delus & Didier François

CNR-IRPI, Research Institute for Geo-Hydrological Protection, Cosenza, Italy

Giuseppe Esposito & Olga Petrucci

INRAE, Bordeaux Sciences Agro, UMR ISPA, Villenave dʼOrnon, France

Frédéric Frappart

University of Saskatchewan, Centre for Hydrology, Canmore, Alberta, Canada

Environmental Policy and Planning Group, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

Animesh K. Gain

Department of Economics, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Venice, Italy

Lab of Geophysical-Remote Sensing & Archaeo-environment, Institute for Mediterranean Studies, Foundation for Research and Technology Hellas, Rethymno, Greece

Manolis Grillakis

Pontificia Bolivariana University, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Bucaramanga, Colombia

Diego A. Guzmán

California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA

Laurie S. Huning

Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research, Palaeoclimate Dynamics Group, Bremerhaven, Germany

Monica Ionita & Viorica Nagavciuc

Emil Racovita Institute of Speleology, Romanian Academy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Monica Ionita

Forest Biometrics Laboratory, Faculty of Forestry, Ștefan cel Mare University, Suceava, Romania

Water Problem Institute Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, Russia

Maxim Kharlamov & Alexey Sazonov

Faculty of Environment, University of Science, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Dao Nguyen Khoi & Pham Thi Thao Nhi

Environment Agency, Bristol, UK

Natalie Kieboom & Hannah Mathew-Richards

School of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, Chania, Greece

Aristeidis Koutroulis

Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú, Lima, Peru

Waldo Lavado-Casimiro

Department of Applied Physics, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

María Carmen LLasat

Water Research Institute, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

British Geological Survey, Wallingford, UK

David Macdonald & Andrew McKenzie

Centre of Natural Hazards and Disaster Science, Uppsala, Sweden

Johanna Mård, Elisa Savelli & Giuliano Di Baldassarre

Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Civil and Environmental Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA

Alfonso Mejia

Escola de Engenharia de Sao Carlos, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil

Eduardo Mario Mendiondo & Felipe Augusto Arguello Souza

Department of Water Resources & Delta Management, Deltares, Delft, the Netherlands

Marjolein Mens

Trelleborg municipality, Trelleborg, Sweden

Shifteh Mobini

Department of Water Resources Engineering, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Shifteh Mobini & Johanna Sörensen

University of Potsdam, Institute of Environmental Science and Geography, Potsdam, Germany

Guilherme Samprogna Mohor & Thorsten Wagener

University of Science and Technology of Hanoi, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam

Thanh Ngo-Duc

Institute for Environment and Resources, Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Thi Thao Nguyen Huynh, Hong Quan Nguyen & Thi Van Thu Tran

Institute for Circular Economy Development, Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Hong Quan Nguyen

Observatori de l’Ebre, Ramon Llull University – CSIC, Roquetes, Spain

Pere Quintana-Seguí

School of Environment and Sustainability, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Saman Razavi

Department of Civil, Geological and Environmental Engineering, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Edile e Ambientale, Sapienza Università di Roma, Rome, Italy

Elena Ridolfi

University of Applied Sciences, Magdeburg, Germany

Jannik Riegel

Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Md Shibly Sadik

Earth and Environmental Systems Institute, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA

Sanjib Sharma

Institute of Meteorology and Water Management National Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland

Wiwiana Szalińska & Tamara Tokarczyk

Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Related Land Surface Processes, Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

Qiuhong Tang & Yueling Wang

Department of Hydraulic Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China

Fuqiang Tian

Royal Botanical Gardens Kew, London, UK

Carolina Tovar

KWR Water Research Institute, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands

Marjolein H. J. Van Huijgevoort

Department of Physical Geography, Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands

Michelle T. H. van Vliet

Civil Engineering, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Thorsten Wagener & Doris E. Wendt

School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA

Elliot Wickham

School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Water Resources Management, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria

Günter Blöschl

Department of Integrated Water Systems and Governance, IHE Delft, Delft, the Netherlands

Giuliano Di Baldassarre

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

H.K. initiated the study and led the work. H.K., A.F.V.L., K. Schröter, P.J.W. and G.D.B. coordinated data collection, designed the study and undertook analyses. All co-authors contributed data and provided conclusions and a synthesis of their case study (the authors of each paired event report were responsible for their case study). M. Mazzoleni additionally designed the figures, and he and N.S. contributed to the analyses. H.K., G.D.B., P.J.W., A.F.V.L., K. Schröter and G.D.B. wrote the manuscript with valuable contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Heidi Kreibich .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature thanks Elizabeth Tellman, Oliver Wing and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended data fig. 1 location of flood and drought paired events coloured according to their indicators-of-change..

a , Change in hazard; b , change in exposure; c , change in vulnerability and d , change in management shortcomings.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Parallel plot of paired events with the same hazard of both events.

The hazard change is zero for all shown paired events. The lines show how the different combinations of indicators-of-change result in varying changes in impacts. Small offsets within the grey bars of the indicator-of-change values enable the visualization of all lines.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Results of the sensitivity analyses.

a–d Correlation matrix of indicators-of-change for 25th and 75th quantiles of correlation coefficients and p-values, respectively ( a , c ) and 75th and 25th quantiles of correlation coefficients and p-values, respectively ( b , d ) separate for flood and drought paired events. Quantiles of correlation coefficients and p-values were calculated separately; colours of squares indicate Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients; sizes of squares indicates p-values. Fig. 2a, c is added to the right to ease comparison.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Theoretical framework used in this study (adapted from IPCC 3 ).

This theoretical risk framework considers impact as a result of three risk components or drivers: hazard, exposure and vulnerability, which in turn are modified by management.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables.

Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Source Data Fig. 1.

Source data fig. 2., source data fig. 3., source data extended data fig. 1., source data extended data fig. 2., source data extended data fig. 3., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kreibich, H., Van Loon, A.F., Schröter, K. et al. The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management. Nature 608 , 80–86 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04917-5

Download citation

Received : 19 August 2021

Accepted : 30 May 2022

Published : 03 August 2022

Issue Date : 04 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04917-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Associations between a cash voucher intervention, food consumption, and coping strategies in somali food-insecure populations.

- Theresa Fang

- Yunhee Kang

Agriculture & Food Security (2024)

Limited progress in global reduction of vulnerability to flood impacts over the past two decades

- Inga J. Sauer

- Benedikt Mester

- Christian Otto

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

- Daniel Nohrstedt

- Elena Mondino

- Charles F. Parker

npj Natural Hazards (2024)

Application of a hybrid algorithm of LSTM and Transformer based on random search optimization for improving rainfall-runoff simulation

- Wenzhong Li

- Chengshuai Liu

Scientific Reports (2024)

Strategic storm flood evacuation planning for large coastal cities enables more effective transfer of elderly populations

- Mingfu Guan

Nature Water (2024)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Login or signup to the library

- my Channels

- All Channels

- List events

- List channels

- List collections

You are here

Landslide mitigation and disaster risk management - case studies and good practice.

Resources on this Collection

Management of Slope Stability in Communities (MoSSaiC) in Saint Lucia

Safer Cities 12 Demonstration Housing Construction for Landslide and Flood Prone Areas A case study from Ratnapura, Sri Lanka

Words into Action Guidelines 3. Landslide Hazard and Risk Assessment

Interaction of Dams and Landslides—Case Studies and Mitigation

Peru – 2012 – Flooding and Land Slides

Nepal: Flood and Landslide

Collections on this collection.

Landslides Mitigation in Shelter and Settlements - Technical Guidelines

Post Disaster Engineering - Reports and Case Studies

Natural Disaster Management in Mozambique

You must be logged in to post a comment

Content Search

World + 7 more

Case Studies: Red Cross Red Crescent Disaster Risk Reduction in Action – What Works at Local Level, June 2018

Attachments.

Community/local action for resilience:

- Building the disaster resilience of asylum seekers

The Australian Red Cross in Queensland adapted a generic preparedness tool to support highrisk marginalised communities of asylum seekers to build their own resilience to disaster. Specific and relevant messaging was developed within a community education programme co-designed with members of the asylum seekers community, who became educators and facilitators to deliver the programme. The programme reached 900 people in a successful pilot, measured through positive shifts in knowledge of key actions to take in preparedness of disaster. The underlying achievement is the acceptance and trust of the communities, reflecting the respect for cultural and language diversity, and recognizing the capacity of asylum seekers communities to contribute and participate in their host country.

- Integrated Coastal Community Resilience and Disaster Risk Reduction in Demak, Central Java

Exacerbated erosion affected the ecology and increased vulnerability of coastal communities in Demak. The Indonesian Red Cross mobilized communities through Community-Based Action Teams to restore the ecosystem through mangrove plantation and implement livelihood generation to improve community resilience. Under an integrated approach, the community is connected with village authorities and scientists from the Bogor Agricultural Institute to implement sustainable local action. The programme has shown concrete results in reducing the risks of tidal disasters, while eco-tourism and crab cultivation farming have increased the income of the communities, along with their heightened awareness and preparedness for disaster.

- Winter shelters for rural herder communities

Rural herders in Mongolia must keep their livestock alive through extreme temperatures and exposure of harsh winters that follow after drought. In efforts to reduce livestock loss, the Red Cross supported herder communities to design and construct winters shelters for livestock in a participatory approach garnering the collective capacity of community, local government and the Red Cross. A strong community focus ensures that the herders drive the activities towards preserving their livelihoods and the traditional nomadic way of life under threat by climatic challenges.

- Youth-led actions for more resilient schools and communities: Mapping of School Safety approaches and Youth in School Safety training for youth facilitators

Over the last two years the Red Cross Red Crescent Southeast Asia Youth Network has improved Youth programming and networks on youth-led initiatives and solutions for DRR. A pilot Youth in School Safety Programme rolled out in six countries, training 150 youth volunteers who in turn conducted countless school safety actions. A comprehensive mapping of school safety actions in all 11 countries of South Asia is underway to showcase activities of RCRC Youth volunteers on the ground.

Private Sector Interventions:

- Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities

Leaders of leading commercial organizations jointly commit resources to work constructively with government to make Australian communities safer and more resilient to natural disasters, by shifting national investment from recovery and response to preparedness and mitigation. The Australian Red Cross joins this Roundtable - contributing on emergency management and humanitarian aspects - to collectively deliver on community education, risk information, adaptation research, mitigation infrastructure and strategic alliances.

Disaster Risk Governance:

- A seat at the table: inclusive decision-making to strengthen local resilience

Disaster related laws and policies need to better include and protect those most at risk of disasters. This case study outlines the steps taken by the IFRC Disaster Law Programme - from global research undertaken jointly by IFRC and UNDP, to the provision of technical advice in supporting Asia Pacific National Societies, as the community-based actor and auxiliary to government, to ensure inclusive community empowerment and protection, gender and inclusion in national disaster laws and policies.

Gender and Inclusiveness:

- Participatory Campaign Planning for Inclusive DRR Knowledge and Messaging in Nepal

An innovative approach that embraces the essence of inclusiveness, the Participatory Campaign Planning methodology is applied to develop hazard messages and the means of communicating them that are tailored to different target groups, with the aim of making them more effective in creating behaviour change. This case study focuses on urban communities in Nepal and various elements to be considered within different target groups and their geographic environments.

- Community participatory action research on sexual and genderbased violence prevention and response during disasters

This collaborative research by the IFRC and the ASEAN Committee for Disaster Management was undertaken in recognizing that there are few SGBV studies that focus on low-income developing countries and fewer that go beyond the gendered effects on women and girls, overlooking men and boys and sexual minority groups. Key findings illustrate that the risks to SGBV are exacerbated during natural disaster situations in Indonesia, Lao PDR and the Philippines, and that “disaster responders” and actors addressing needs of SGBV survivors are not working together adequately to reduce these risks.

Early Warning and Early Action:

- Forecast-based Financing: Effective early actions to reduce flood impacts

When four pilot communities in the district of Bogura were affected by severe flood events in July and August of 2017, the Early Action Protocol of the Forecast-based Financing (FbF) approach was activated, and unconditional cash grant was chosen as the early action for floods to give people the flexibility to prepare individually for the impending flood and take the measures they see fit. This case study outlines the steps taken by Bangladesh Red Crescent Society and German Red Cross to implement FbF in Bangladesh. It analyses not only the effectiveness of the activation in Bogura, but the longer term impacts of this early action development.

- CPP Early Warning: Saving Thousands in Cyclone Mora

Through the Bangladesh Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP) interventions, a programme jointly run by the Government of Bangladesh and the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society (BDRCS), the communities of the coastal areas in Bangladesh have become more aware of the need to go to safe shelters during emergencies, have understood the significance of early warning and learned to pay heed to advice from CPP and youth volunteers. On 28 May 2017 - the eve of Cyclone Mora, more than 55,260 CPP volunteers and BDRCS youth volunteers were deployed to pass early warning message door to door in the coastal region, and announcing the danger of the approaching cyclone in the local language. Cyclone early warning messages were disseminated across a population area covering 11 million people, and almost half a million people were reached in this process and taken to safe places in less than 24 hours. The CPP has substantially reduce death tolls due to cyclones in Bangladesh.

- Flood Early Warning and Early Action System (FEWEAS)

The Flood Early Warning Early Action System (FEWEAS) was developed through a collaboration between the Indonesian Red Cross (PMI) and Institute Teknologi Bandung (ITB) to provide effective solutions for reducing disaster risk through a shared platform for community and government to address issues upstream and downstream in formulating appropriate strategy, planning and ground action for floods. FEWEAS is an internet-based application to predict and monitor rainfall and flooding. PMI Provincial and District staff and volunteers are using the FEWEAS to monitor floods along the Bengawan Solo River in East Java, and along the Citarum River in West Java. While the application provides flood alerts and updates to the community through smartphones, the communities and Community Based Action Teams can update their response, upload photos, videos and relevant information to further inform response actions.

- Forecast-based Financing for the vulnerable herders in Mongolia

The Mongolian Red Cross Society (MRCS) assisted 2,000 herder households in most-at-risk areas (40 soums in 12 provinces) with unrestricted cash grants in December 2017 and with animal care kits in January 2018, before the peak of the winter season. The MRCS used the Dzud Risk Map released by the Government in November 2017 to decide which soums to target for early action with the aim to reach the herders well before the loss of their livestock to reduce the impact of Dzud on the livelihoods of the herders. The Dzud Risk Map highlighted the risk of livestock death throughout the whole of Mongolia. A cost-benefit analysis is being conducted to further inform FbF in Mongolia.

- More than response: Building partnerships to engage communities in preparedness and early warning systems in the Pacific

A community early warning system (CEWS) model was developed in partnership by the Red Cross, government agencies and regional organizations in the Pacific to better link CEWS with national and sub-national systems. Taking these pilots to scale requires i) national mechanisms such as SOPs and action plans that systematically link warnings and climate information provided by National Meteorological Services to early preparedness actions at multiple scales, and; ii) available funding (at multiple scales) to support early actions. Recently a Roadmap for Forecast-based Financing for Drought Preparedness has been developed in the Solomon Islands. Through continued partnership approach, the Roadmap and outcomes from the regional ‘FINPAC’ CEWS project will be used to support the Government of the Solomon Islands and Solomon Islands Red Cross to implement a programme for communities, provincial and national authorities to apply forecast information for early action at scale. The drought thresholds developed in collaboration will form the basis of an FbF trigger system in the Solomon Islands.