How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography

- Critical Appraisal & Analysis

Sample Annotations

Attributions.

- Citation Styles

Need Help? Ask Us.

Hesburgh Library First Floor University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, IN 46556

(574) 631-6258 [email protected]

Chat with us!

SAMPLE DESCRIPTIVE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ENTRY FOR A JOURNAL ARTICLE

The following example uses the APA format for the journal citation.

Waite, L. J., Goldschneider, F. K., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554.

This example uses the MLA format for the journal citation. NOTE: Standard MLA practice requires double spacing within citations.

Waite, Linda J., Frances Kobrin Goldscheider, and Christina Witsberger. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review 51.4 (1986): 541-554. Print.

More Sample Annotations

- Annotated Bibliography Examples

- Annotated Bibliography Samples

The University of Toronto offers an example that illustrates how to summarize a study's research methods and argument.

The Memorial University of Newfoundland presents these examples of both descriptive and critical annotations.

The Writing Center at the University of Wisconsin gives examples of the some of the most common forms of annotated bibliographies.

The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina gives examples of several different forms of annotated bibliographies in 3 popular citation formats:

- MLA Example

- APA Example

- CBE Example

This page was adapted with permission from the following:

http://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

How to prepare an annotated bibliography Research & Learning Services Olin Library Cornell University Library Ithaca, NY, USA

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal & Analysis

- Next: Process >>

- Last Updated: Jul 28, 2022 10:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.nd.edu/annotated-bibliography

Need help? Ask us.

| Visit the Ask Us Desk 1st Floor, Hesburgh Library |

Report a problem

- Research Guides

- CECH Library

How to Write an Annotated Bibliography

Writing annotations.

- Introduction

- New RefWorks

- Formatting Citations

- Sample Annotated Bibliographies

An annotation is a brief note following each citation listed on an annotated bibliography. The goal is to briefly summarize the source and/or explain why it is important for a topic. They are typically a single concise paragraph, but might be longer if you are summarizing and evaluating.

Annotations can be written in a variety of different ways and it’s important to consider the style you are going to use. Are you simply summarizing the sources, or evaluating them? How does the source influence your understanding of the topic? You can follow any style you want if you are writing for your own personal research process, but consult with your professor if this is an assignment for a class.

Annotation Styles

- Combined Informative/Evaluative Style - This style is recommended by the library as it combines all the styles to provide a more complete view of a source. The annotation should explain the value of the source for the overall research topic by providing a summary combined with an analysis of the source.

Aluedse, O. (2006). Bullying in schools: A form of child abuse in schools. Educational Research Quarterly , 30 (1), 37.

The author classifies bullying in schools as a “form of child abuse,” and goes well beyond the notion that schoolyard bullying is “just child’s play.” The article provides an in-depth definition of bullying, and explores the likelihood that school-aged bullies may also experience difficult lives as adults. The author discusses the modern prevalence of bullying in school systems, the effects of bullying, intervention strategies, and provides an extensive list of resources and references.

Statistics included provide an alarming realization that bullying is prevalent not only in the United States, but also worldwide. According to the author, “American schools harbor approximately 2.1 million bullies and 2.7 million victims.” The author references the National Association of School Psychologists and quotes, “Thus, one in seven children is a bully or a target of bullying.” A major point of emphasis centers around what has always been considered a “normal part of growing up” versus the levels of actual abuse reached in today’s society.

The author concludes with a section that addresses intervention strategies for school administrators, teachers, counselors, and school staff. The concept of school staff helping build students’ “social competence” is showcased as a prevalent means of preventing and reducing this growing social menace. Overall, the article is worthwhile for anyone interested in the subject matter, and provides a wealth of resources for researching this topic of growing concern.

(Renfrow & Teuton, 2008)

- Informative Style - Similar to an abstract, this style focuses on the summarizing the source. The annotation should identify the hypothesis, results, and conclusions presented by the source.

Plester, B., Wood, C, & Bell, V. (2008). Txt msg n school literacy: Does texting and knowledge of text abbreviations adversely affect children's literacy attainment? Literacy , 42(3), 137-144.

Reports on two studies that investigated the relationship between children's texting behavior, their knowledge of text abbreviations, and their school attainment in written language skills. In Study One, 11 to 12 year-old children reported their texting behavior and translated a standard English sentence into a text message and vice versa. In Study Two, children's performance on writing measures were examined more specifically, spelling proficiency was also assessed, and KS2 Writing scores were obtained. Positive correlations between spelling ability and performance on the translation exercise were found, and group-based comparisons based on the children's writing scores also showed that good writing attainment was associated with greater use of texting abbreviations (textisms), although the direction of this association is not clear. Overall, these findings suggest that children's knowledge of textisms is not associated with poor written language outcomes for children in this age range.

(Beach et al., 2009)

- Evaluative Style - This style analyzes and critically evaluates the source. The annotation should comment on the source's the strengths, weaknesses, and how it relates to the overall research topic.

Amott, T. (1993). Caught in the Crisis: Women in the U.S. Economy Today . New York: Monthly Review Press.

A very readable (140 pp) economic analysis and information book which I am currently considering as a required collateral assignment in Economics 201. Among its many strengths is a lucid connection of "The Crisis at Home" with the broader, macroeconomic crisis of the U.S. working class (which various other authors have described as the shrinking middle class or the crisis of de-industrialization).

(Papadantonakis, 1996)

- Indicative Style - This style of annotation identifies the main theme and lists the significant topics included in the source. Usually no specific details are given beyond the topic list .

Example:

Gambell, T.J., & Hunter, D. M. (1999). Rethinking gender differences in literacy. Canadian Journal of Education , 24(1) 1-16.

Five explanations are offered for recently assessed gender differences in the literacy achievement of male and female students in Canada and other countries. The explanations revolve around evaluative bias, home socialization, role and societal expectations, male psychology, and equity policy.

(Kerka & Imel, 2004)

Beach, R., Bigelow, M., Dillon, D., Dockter, J., Galda, L., Helman, L., . . . Janssen, T. (2009). Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Research in the Teaching of English, 44 (2), 210-241. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784357

Kerka, S., & Imel, S. (2004). Annotated bibliography: Women and literacy. Women's Studies Quarterly, 32 (1), 258-271. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/233645656?accountid=2909

Papadantonakis, K. (1996). Selected Annotated Bibliography for Economists and Other Social Scientists. Women's Studies Quarterly, 24 (3/4), 233-238. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40004384

Renfrow, T.G., & Teuton, L.M. (2008). Schoolyard bullying: Peer victimization an annotated bibliography. Community & Junior College Libraries, 14(4), 251-275. doi:10.1080/02763910802336407

- << Previous: Formatting Citations

- Next: Sample Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Jul 1, 2024 1:59 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/annotated_bibliography

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

- Phoenix College

BIO181: General Biology (Alu Sequences)

- Annotating a Scientific Paper

- Locating Primary Literature

- Paraphrasing

- In-Text Citations

- Genetic Disorders Research Guide This link opens in a new window

Sample Annotated Papers

- Dosage compensation via transposable element mediated rewiring of a regulatory network

- BRCA1 tumor suppression depends on BRCT phosphoprotein binding, but not its E3 ligase activity

- The mutagenic chain reaction: A method for converting heterozygous to homozygous mutations

Components of Scientific Research Articles

Introduction.

Steps to Annotating A Scientific Paper

- Locate each of the components (Abstract, Introduction, etc.)

- Identify unfamiliar words in these sections that are important to understanding the research.

- Define the unfamiliar words. Use Google or Credo Reference dictionaries. Try NHGRI Talking Glossary of Genetic Terms or Scitable Glossary from Nature .

- Annotate each section by summarizing the main idea or paraphrasing important sentences. Write to an audience of first-year college students.

Science in the Classroom

Science in the Classroom (SitC) features annotated research articles published in the Science family of journals. SitC uses 7 categories of annotations, each called a "LEARNING LENS" - - Glossary, Previous work [Introduction], Author's experiments [Methods], Results and Conclusions, News and policy links, Learning standards, and References and notes. Click on each LEARNING LENS to turn annotations on and off. Figures in the papers also have tabs with more detailed explanations to help the reader.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Locating Primary Literature >>

- Last Updated: Sep 14, 2023 12:26 PM

- URL: https://phoenixcollege.libguides.com/BIO181/Alu

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Citing sources

- What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format

What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format

Published on March 9, 2021 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on August 23, 2022.

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that includes a short descriptive text (an annotation) for each source. It may be assigned as part of the research process for a paper , or as an individual assignment to gather and read relevant sources on a topic.

Scribbr’s free Citation Generator allows you to easily create and manage your annotated bibliography in APA or MLA style. To generate a perfectly formatted annotated bibliography, select the source type, fill out the relevant fields, and add your annotation.

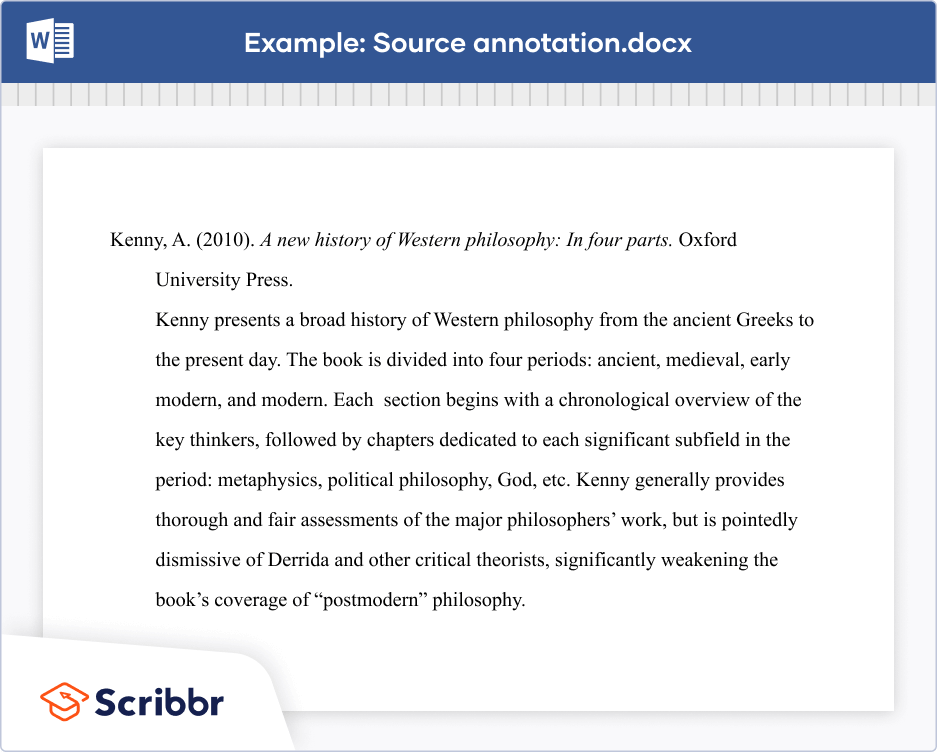

An example of an annotated source is shown below:

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Annotated bibliography format: apa, mla, chicago, how to write an annotated bibliography, descriptive annotation example, evaluative annotation example, reflective annotation example, finding sources for your annotated bibliography, frequently asked questions about annotated bibliographies.

Make sure your annotated bibliography is formatted according to the guidelines of the style guide you’re working with. Three common styles are covered below:

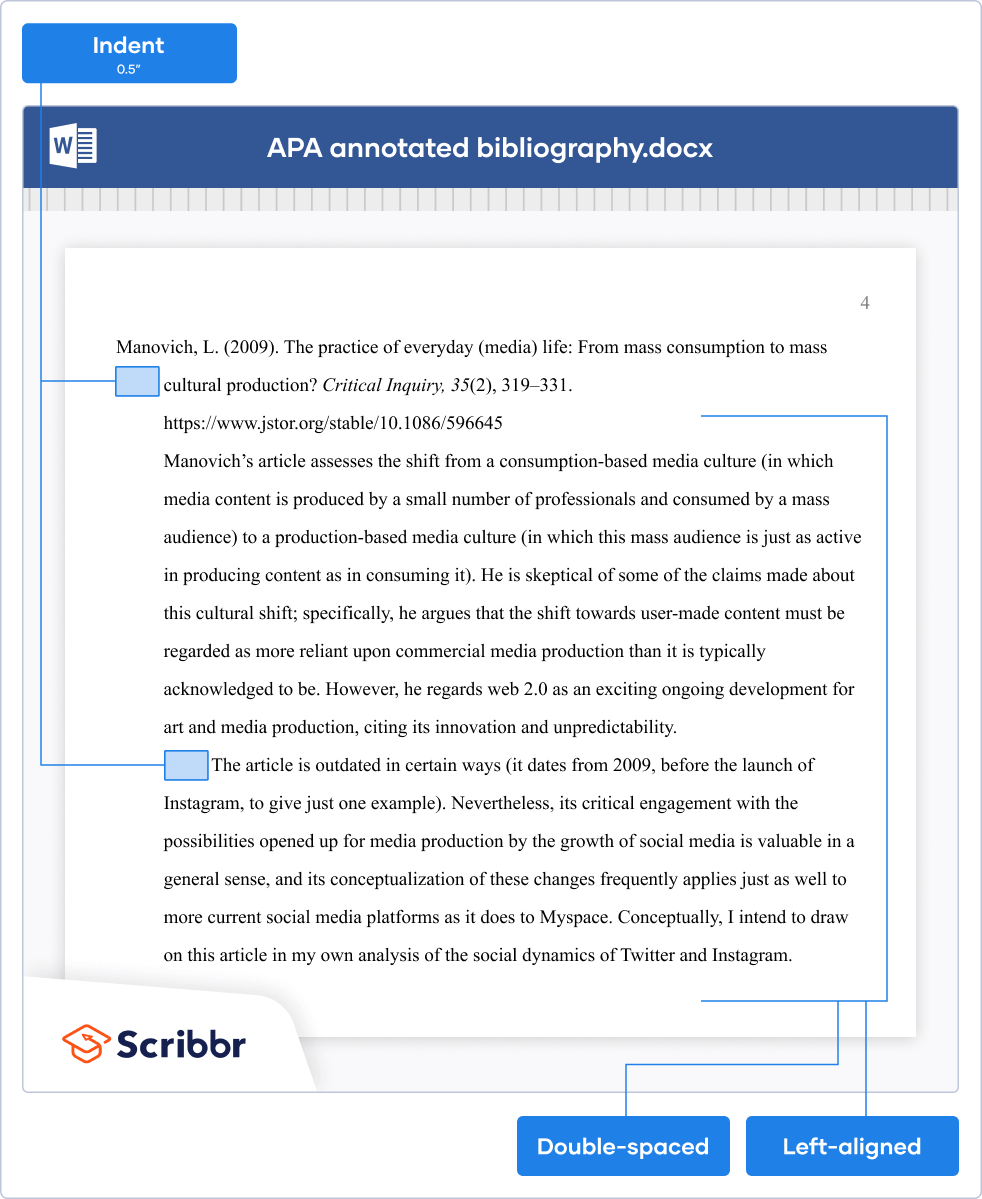

In APA Style , both the reference entry and the annotation should be double-spaced and left-aligned.

The reference entry itself should have a hanging indent . The annotation follows on the next line, and the whole annotation should be indented to match the hanging indent. The first line of any additional paragraphs should be indented an additional time.

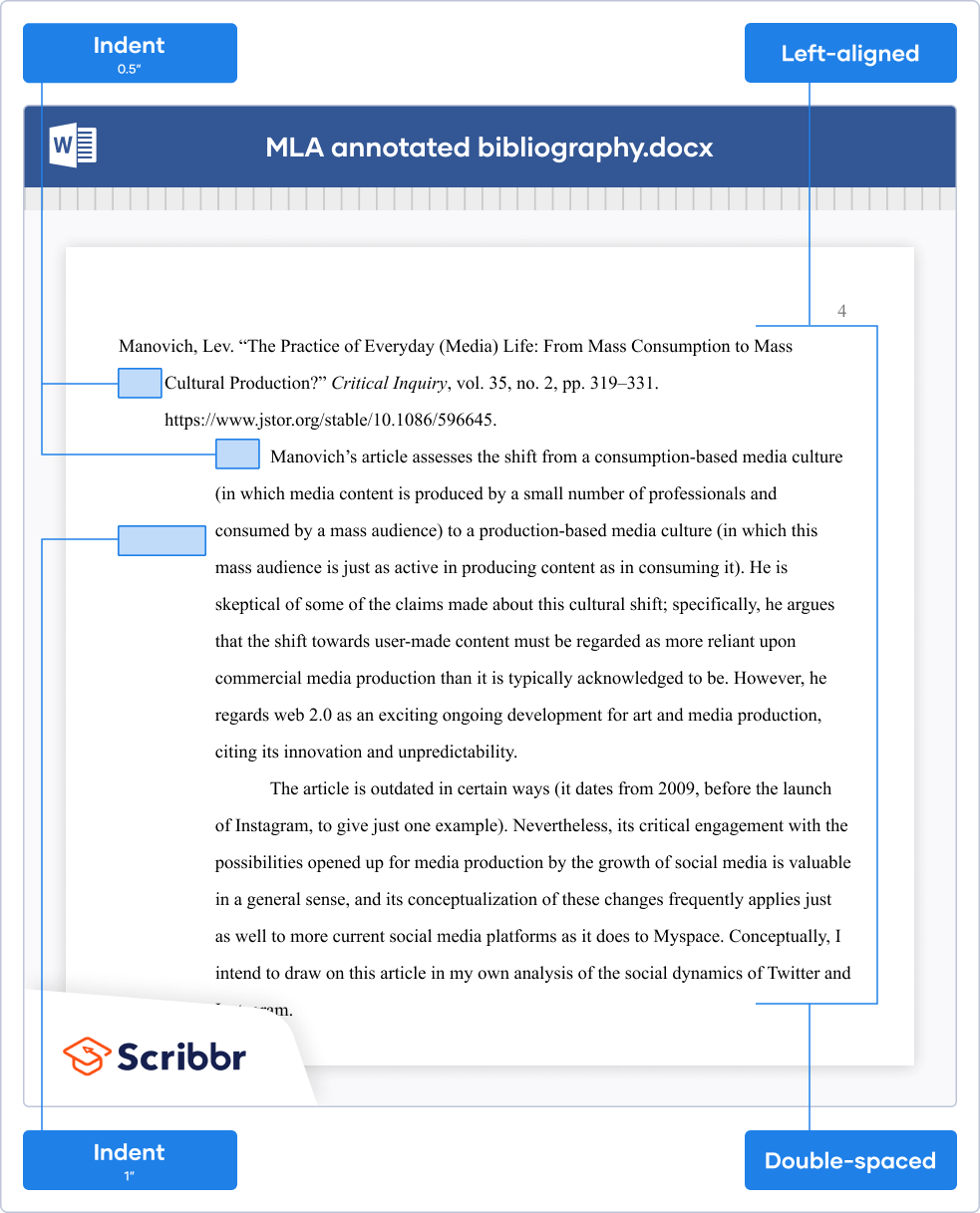

In an MLA style annotated bibliography , the Works Cited entry and the annotation are both double-spaced and left-aligned.

The Works Cited entry has a hanging indent. The annotation itself is indented 1 inch (twice as far as the hanging indent). If there are two or more paragraphs in the annotation, the first line of each paragraph is indented an additional half-inch, but not if there is only one paragraph.

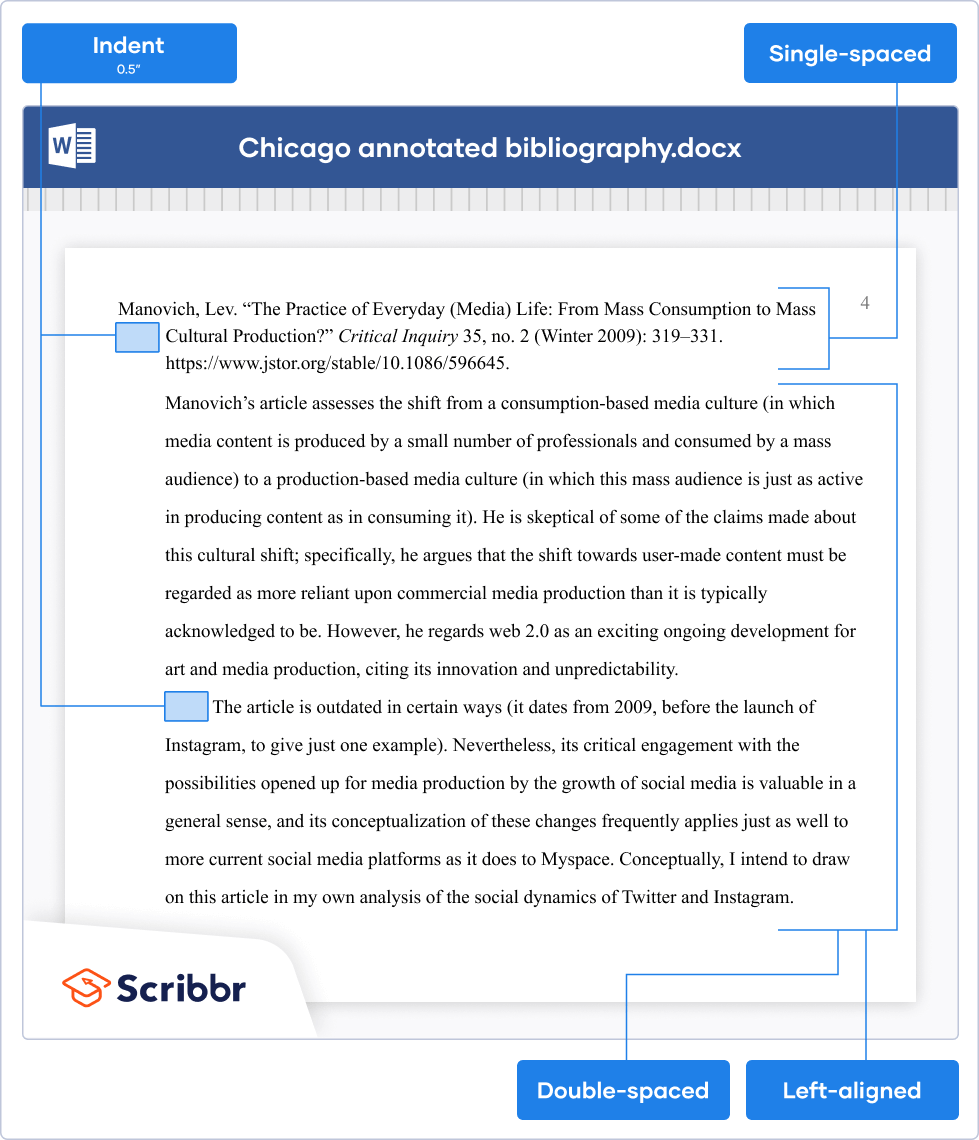

Chicago style

In a Chicago style annotated bibliography , the bibliography entry itself should be single-spaced and feature a hanging indent.

The annotation should be indented, double-spaced, and left-aligned. The first line of any additional paragraphs should be indented an additional time.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

For each source, start by writing (or generating ) a full reference entry that gives the author, title, date, and other information. The annotated bibliography format varies based on the citation style you’re using.

The annotations themselves are usually between 50 and 200 words in length, typically formatted as a single paragraph. This can vary depending on the word count of the assignment, the relative length and importance of different sources, and the number of sources you include.

Consider the instructions you’ve been given or consult your instructor to determine what kind of annotations they’re looking for:

- Descriptive annotations : When the assignment is just about gathering and summarizing information, focus on the key arguments and methods of each source.

- Evaluative annotations : When the assignment is about evaluating the sources , you should also assess the validity and effectiveness of these arguments and methods.

- Reflective annotations : When the assignment is part of a larger research process, you need to consider the relevance and usefulness of the sources to your own research.

These specific terms won’t necessarily be used. The important thing is to understand the purpose of your assignment and pick the approach that matches it best. Interactive examples of the different styles of annotation are shown below.

A descriptive annotation summarizes the approach and arguments of a source in an objective way, without attempting to assess their validity.

In this way, it resembles an abstract , but you should never just copy text from a source’s abstract, as this would be considered plagiarism . You’ll naturally cover similar ground, but you should also consider whether the abstract omits any important points from the full text.

The interactive example shown below describes an article about the relationship between business regulations and CO 2 emissions.

Rieger, A. (2019). Doing business and increasing emissions? An exploratory analysis of the impact of business regulation on CO 2 emissions. Human Ecology Review , 25 (1), 69–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26964340

An evaluative annotation also describes the content of a source, but it goes on to evaluate elements like the validity of the source’s arguments and the appropriateness of its methods .

For example, the following annotation describes, and evaluates the effectiveness of, a book about the history of Western philosophy.

Kenny, A. (2010). A new history of Western philosophy: In four parts . Oxford University Press.

A reflective annotation is similar to an evaluative one, but it focuses on the source’s usefulness or relevance to your own research.

Reflective annotations are often required when the point is to gather sources for a future research project, or to assess how they were used in a project you already completed.

The annotation below assesses the usefulness of a particular article for the author’s own research in the field of media studies.

Manovich, Lev. (2009). The practice of everyday (media) life: From mass consumption to mass cultural production? Critical Inquiry , 35 (2), 319–331. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/596645

Manovich’s article assesses the shift from a consumption-based media culture (in which media content is produced by a small number of professionals and consumed by a mass audience) to a production-based media culture (in which this mass audience is just as active in producing content as in consuming it). He is skeptical of some of the claims made about this cultural shift; specifically, he argues that the shift towards user-made content must be regarded as more reliant upon commercial media production than it is typically acknowledged to be. However, he regards web 2.0 as an exciting ongoing development for art and media production, citing its innovation and unpredictability.

The article is outdated in certain ways (it dates from 2009, before the launch of Instagram, to give just one example). Nevertheless, its critical engagement with the possibilities opened up for media production by the growth of social media is valuable in a general sense, and its conceptualization of these changes frequently applies just as well to more current social media platforms as it does to Myspace. Conceptually, I intend to draw on this article in my own analysis of the social dynamics of Twitter and Instagram.

Before you can write your annotations, you’ll need to find sources . If the annotated bibliography is part of the research process for a paper, your sources will be those you consult and cite as you prepare the paper. Otherwise, your assignment and your choice of topic will guide you in what kind of sources to look for.

Make sure that you’ve clearly defined your topic , and then consider what keywords are relevant to it, including variants of the terms. Use these keywords to search databases (e.g., Google Scholar ), using Boolean operators to refine your search.

Sources can include journal articles, books, and other source types , depending on the scope of the assignment. Read the abstracts or blurbs of the sources you find to see whether they’re relevant, and try exploring their bibliographies to discover more. If a particular source keeps showing up, it’s probably important.

Once you’ve selected an appropriate range of sources, read through them, taking notes that you can use to build up your annotations. You may even prefer to write your annotations as you go, while each source is fresh in your mind.

An annotated bibliography is an assignment where you collect sources on a specific topic and write an annotation for each source. An annotation is a short text that describes and sometimes evaluates the source.

Any credible sources on your topic can be included in an annotated bibliography . The exact sources you cover will vary depending on the assignment, but you should usually focus on collecting journal articles and scholarly books . When in doubt, utilize the CRAAP test !

Each annotation in an annotated bibliography is usually between 50 and 200 words long. Longer annotations may be divided into paragraphs .

The content of the annotation varies according to your assignment. An annotation can be descriptive, meaning it just describes the source objectively; evaluative, meaning it assesses its usefulness; or reflective, meaning it explains how the source will be used in your own research .

A source annotation in an annotated bibliography fulfills a similar purpose to an abstract : they’re both intended to summarize the approach and key points of a source.

However, an annotation may also evaluate the source , discussing the validity and effectiveness of its arguments. Even if your annotation is purely descriptive , you may have a different perspective on the source from the author and highlight different key points.

You should never just copy text from the abstract for your annotation, as doing so constitutes plagiarism .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2022, August 23). What Is an Annotated Bibliography? | Examples & Format. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/citing-sources/annotated-bibliography/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, evaluating sources | methods & examples, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc., hanging indent | word & google docs instructions, scribbr apa citation checker.

An innovative new tool that checks your APA citations with AI software. Say goodbye to inaccurate citations!

Biology 204 - Biological Research Experience: Molecules to Ecosystems

- Scientific Article Discovery

- Examples of "Ecology" Citation Style

- Getting Started With Annotated Bibliographies

- Image Sources

- Bates Biology Department On-Line Resources Page This link opens in a new window

What is an annotated bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to sources, such as books and articles. Each citation is followed by an annotation, a brief descriptive and evaluative paragraph, about 150 words long, that analyzes the source. An annotated bibliography usually looks like any other bibliography with alphabetized citations of sources, except that here each source is followed by an explanatory paragraph. This work can form the basis of a literature review later in the writing process. The purpose of the annotation is to inform on the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

What isn't an annotated bibliography?

An annotation is not only a summary of the source in question. It should be a short but critical analysis as to why and how the source fits into the larger research question. An abstract functions as a summary, an annotation should be contextual to the specific topic at hand. It should be both descriptive and evaluative.

Types of annotations:

- Descriptive : states the topic of the source only

- Evaluative : evaluates the source, which may include placing the work in context of other research or evaluating its usefulness. This is the type expected for most research assignments.

- Summary : summarizes the source but does not take a stance or make an argument about the source.

What about formatting?

Most of the major citation styles call for a hanging first line on annotated bibliographies. This means the first line of the citation will align with the left margin of the page, and all subsequent lines of the citation and annotation will indent to the right.

Example of an Annotated Citation using the Ecology Journal Style

Patra, A., T. Park, M. Kim, and Z. Yu. 2017. "Rumen Methanogens and Mitigation Of Methane Emission by Anti-Methanogenic Compounds and Substances." Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 8 :13.

This study reviews some of the work to date (2017) identifying ruminal methanogens and the in vivo and in vitro effects of anti-methanogenic compounds. Of specific interest is the summary of evidence suggesting that archaea make up only ~10% of the ruminal microbiome (see "Overview of methanogens present in the rumen"). Also of note, this paper cites work indicating many rumen ciliate protozoa have ecto- and endo-associated methanogenic archaea (see "Methanogens associated with rumen protozoa"). However, most ruminal methanogens are "free-living" (i.e. not protozoa-associated; see "Free-living ruminal methanogens").

- << Previous: Examples of "Ecology" Citation Style

- Next: Image Sources >>

- Updated: Apr 11, 2024 3:36 PM

- URL: https://libguides.bates.edu/bio204

How to Annotate Texts

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Annotation Fundamentals

How to start annotating , how to annotate digital texts, how to annotate a textbook, how to annotate a scholarly article or book, how to annotate literature, how to annotate images, videos, and performances, additional resources for teachers.

Writing in your books can make you smarter. Or, at least (according to education experts), annotation–an umbrella term for underlining, highlighting, circling, and, most importantly, leaving comments in the margins–helps students to remember and comprehend what they read. Annotation is like a conversation between reader and text. Proper annotation allows students to record their own opinions and reactions, which can serve as the inspiration for research questions and theses. So, whether you're reading a novel, poem, news article, or science textbook, taking notes along the way can give you an advantage in preparing for tests or writing essays. This guide contains resources that explain the benefits of annotating texts, provide annotation tools, and suggest approaches for diverse kinds of texts; the last section includes lesson plans and exercises for teachers.

Why annotate? As the resources below explain, annotation allows students to emphasize connections to material covered elsewhere in the text (or in other texts), material covered previously in the course, or material covered in lectures and discussion. In other words, proper annotation is an organizing tool and a time saver. The links in this section will introduce you to the theory, practice, and purpose of annotation.

How to Mark a Book, by Mortimer Adler

This famous, charming essay lays out the case for marking up books, and provides practical suggestions at the end including underlining, highlighting, circling key words, using vertical lines to mark shifts in tone/subject, numbering points in an argument, and keeping track of questions that occur to you as you read.

How Annotation Reshapes Student Thinking (TeacherHUB)

In this article, a high school teacher discusses the importance of annotation and how annotation encourages more effective critical thinking.

The Future of Annotation (Journal of Business and Technical Communication)

This scholarly article summarizes research on the benefits of annotation in the classroom and in business. It also discusses how technology and digital texts might affect the future of annotation.

Annotating to Deepen Understanding (Texas Education Agency)

This website provides another introduction to annotation (designed for 11th graders). It includes a helpful section that teaches students how to annotate reading comprehension passages on tests.

Once you understand what annotation is, you're ready to begin. But what tools do you need? How do you prepare? The resources linked in this section list strategies and techniques you can use to start annotating.

What is Annotating? (Charleston County School District)

This resource gives an overview of annotation styles, including useful shorthands and symbols. This is a good place for a student who has never annotated before to begin.

How to Annotate Text While Reading (YouTube)

This video tutorial (appropriate for grades 6–10) explains the basic ins and outs of annotation and gives examples of the type of information students should be looking for.

Annotation Practices: Reading a Play-text vs. Watching Film (U Calgary)

This blog post, written by a student, talks about how the goals and approaches of annotation might change depending on the type of text or performance being observed.

Annotating Texts with Sticky Notes (Lyndhurst Schools)

Sometimes students are asked to annotate books they don't own or can't write in for other reasons. This resource provides some strategies for using sticky notes instead.

Teaching Students to Close Read...When You Can't Mark the Text (Performing in Education)

Here, a sixth grade teacher demonstrates the strategies she uses for getting her students to annotate with sticky notes. This resource includes a link to the teacher's free Annotation Bookmark (via Teachers Pay Teachers).

Digital texts can present a special challenge when it comes to annotation; emerging research suggests that many students struggle to critically read and retain information from digital texts. However, proper annotation can solve the problem. This section contains links to the most highly-utilized platforms for electronic annotation.

Evernote is one of the two big players in the "digital annotation apps" game. In addition to allowing users to annotate digital documents, the service (for a fee) allows users to group multiple formats (PDF, webpages, scanned hand-written notes) into separate notebooks, create voice recordings, and sync across all sorts of devices.

OneNote is Evernote's main competitor. Reviews suggest that OneNote allows for more freedom for digital note-taking than Evernote, but that it is slightly more awkward to import and annotate a PDF, especially on certain platforms. However, OneNote's free version is slightly more feature-filled, and OneNote allows you to link your notes to time stamps on an audio recording.

Diigo is a basic browser extension that allows a user to annotate webpages. Diigo also offers a Screenshot app that allows for direct saving to Google Drive.

While the creators of Hypothesis like to focus on their app's social dimension, students are more likely to be interested in the private highlighting and annotating functions of this program.

Foxit PDF Reader

Foxit is one of the leading PDF readers. Though the full suite must be purchased, Foxit offers a number of annotation and highlighting tools for free.

Nitro PDF Reader

This is another well-reviewed, free PDF reader that includes annotation and highlighting. Annotation, text editing, and other tools are included in the free version.

Goodreader is a very popular Mac-only app that includes annotation and editing tools for PDFs, Word documents, Powerpoint, and other formats.

Although textbooks have vocabulary lists, summaries, and other features to emphasize important material, annotation can allow students to process information and discover their own connections. This section links to guides and video tutorials that introduce you to textbook annotation.

Annotating Textbooks (Niagara University)

This PDF provides a basic introduction as well as strategies including focusing on main ideas, working by section or chapter, annotating in your own words, and turning section headings into questions.

A Simple Guide to Text Annotation (Catawba College)

The simple, practical strategies laid out in this step-by-step guide will help students learn how to break down chapters in their textbooks using main ideas, definitions, lists, summaries, and potential test questions.

Annotating (Mercer Community College)

This packet, an excerpt from a literature textbook, provides a short exercise and some examples of how to do textbook annotation, including using shorthand and symbols.

Reading Your Healthcare Textbook: Annotation (Saddleback College)

This powerpoint contains a number of helpful suggestions, especially for students who are new to annotation. It emphasizes limited highlighting, lots of student writing, and using key words to find the most important information in a textbook. Despite the title, it is useful to a student in any discipline.

Annotating a Textbook (Excelsior College OWL)

This video (with included transcript) discusses how to use textbook features like boxes and sidebars to help guide annotation. It's an extremely helpful, detailed discussion of how textbooks are organized.

Because scholarly articles and books have complex arguments and often depend on technical vocabulary, they present particular challenges for an annotating student. The resources in this section help students get to the heart of scholarly texts in order to annotate and, by extension, understand the reading.

Annotating a Text (Hunter College)

This resource is designed for college students and shows how to annotate a scholarly article using highlighting, paraphrase, a descriptive outline, and a two-margin approach. It ends with a sample passage marked up using the strategies provided.

Guide to Annotating the Scholarly Article (ReadWriteThink.org)

This is an effective introduction to annotating scholarly articles across all disciplines. This resource encourages students to break down how the article uses primary and secondary sources and to annotate the types of arguments and persuasive strategies (synthesis, analysis, compare/contrast).

How to Highlight and Annotate Your Research Articles (CHHS Media Center)

This video, developed by a high school media specialist, provides an effective beginner-level introduction to annotating research articles.

How to Read a Scholarly Book (AndrewJacobs.org)

In this essay, a college professor lets readers in on the secrets of scholarly monographs. Though he does not discuss annotation, he explains how to find a scholarly book's thesis, methodology, and often even a brief literature review in the introduction. This is a key place for students to focus when creating annotations.

A 5-step Approach to Reading Scholarly Literature and Taking Notes (Heather Young Leslie)

This resource, written by a professor of anthropology, is an even more comprehensive and detailed guide to reading scholarly literature. Combining the annotation techniques above with the reading strategy here allows students to process scholarly book efficiently.

Annotation is also an important part of close reading works of literature. Annotating helps students recognize symbolism, double meanings, and other literary devices. These resources provide additional guidelines on annotating literature.

AP English Language Annotation Guide (YouTube)

In this ~10 minute video, an AP Language teacher provides tips and suggestions for using annotations to point out rhetorical strategies and other important information.

Annotating Text Lesson (YouTube)

In this video tutorial, an English teacher shows how she uses the white board to guide students through annotation and close reading. This resource uses an in-depth example to model annotation step-by-step.

Close Reading a Text and Avoiding Pitfalls (Purdue OWL)

This resources demonstrates how annotation is a central part of a solid close reading strategy; it also lists common mistakes to avoid in the annotation process.

AP Literature Assignment: Annotating Literature (Mount Notre Dame H.S.)

This brief assignment sheet contains suggestions for what to annotate in a novel, including building connections between parts of the book, among multiple books you are reading/have read, and between the book and your own experience. It also includes samples of quality annotations.

AP Handout: Annotation Guide (Covington Catholic H.S.)

This annotation guide shows how to keep track of symbolism, figurative language, and other devices in a novel using a highlighter, a pencil, and every part of a book (including the front and back covers).

In addition to written resources, it's possible to annotate visual "texts" like theatrical performances, movies, sculptures, and paintings. Taking notes on visual texts allows students to recall details after viewing a resource which, unlike a book, can't be re-read or re-visited ( for example, a play that has finished its run, or an art exhibition that is far away). These resources draw attention to the special questions and techniques that students should use when dealing with visual texts.

How to Take Notes on Videos (U of Southern California)

This resource is a good place to start for a student who has never had to take notes on film before. It briefly outlines three general approaches to note-taking on a film.

How to Analyze a Movie, Step-by-Step (San Diego Film Festival)

This detailed guide provides lots of tips for film criticism and analysis. It contains a list of specific questions to ask with respect to plot, character development, direction, musical score, cinematography, special effects, and more.

How to "Read" a Film (UPenn)

This resource provides an academic perspective on the art of annotating and analyzing a film. Like other resources, it provides students a checklist of things to watch out for as they watch the film.

Art Annotation Guide (Gosford Hill School)

This resource focuses on how to annotate a piece of art with respect to its formal elements like line, tone, mood, and composition. It contains a number of helpful questions and relevant examples.

Photography Annotation (Arts at Trinity)

This resource is designed specifically for photography students. Like some of the other resources on this list, it primarily focuses on formal elements, but also shows students how to integrate the specific technical vocabulary of modern photography. This resource also contains a number of helpful sample annotations.

How to Review a Play (U of Wisconsin)

This resource from the University of Wisconsin Writing Center is designed to help students write a review of a play. It contains suggested questions for students to keep in mind as they watch a given production. This resource helps students think about staging, props, script alterations, and many other key elements of a performance.

This section contains links to lessons plans and exercises suitable for high school and college instructors.

Beyond the Yellow Highlighter: Teaching Annotation Skills to Improve Reading Comprehension (English Journal)

In this journal article, a high school teacher talks about her approach to teaching annotation. This article makes a clear distinction between annotation and mere highlighting.

Lesson Plan for Teaching Annotation, Grades 9–12 (readwritethink.org)

This lesson plan, published by the National Council of Teachers of English, contains four complete lessons that help introduce high school students to annotation.

Teaching Theme Using Close Reading (Performing in Education)

This lesson plan was developed by a middle school teacher, and is aligned to Common Core. The teacher presents her strategies and resources in comprehensive fashion.

Analyzing a Speech Using Annotation (UNC-TV/PBS Learning Media)

This complete lesson plan, which includes a guide for the teacher and relevant handouts for students, will prepare students to analyze both the written and presentation components of a speech. This lesson plan is best for students in 6th–10th grade.

Writing to Learn History: Annotation and Mini-Writes (teachinghistory.org)

This teaching guide, developed for high school History classes, provides handouts and suggested exercises that can help students become more comfortable with annotating historical sources.

Writing About Art (The College Board)

This Prezi presentation is useful to any teacher introducing students to the basics of annotating art. The presentation covers annotating for both formal elements and historical/cultural significance.

Film Study Worksheets (TeachWithMovies.org)

This resource contains links to a general film study worksheet, as well as specific worksheets for novel adaptations, historical films, documentaries, and more. These resources are appropriate for advanced middle school students and some high school students.

Annotation Practice Worksheet (La Guardia Community College)

This worksheet has a sample text and instructions for students to annotate it. It is a useful resource for teachers who want to give their students a chance to practice, but don't have the time to select an appropriate piece of text.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1956 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 41,253 quotes across 1956 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

Annotating Texts

What is annotation.

Annotation can be:

- A systematic summary of the text that you create within the document

- A key tool for close reading that helps you uncover patterns, notice important words, and identify main points

- An active learning strategy that improves comprehension and retention of information

Why annotate?

- Isolate and organize important material

- Identify key concepts

- Monitor your learning as you read

- Make exam prep effective and streamlined

- Can be more efficient than creating a separate set of reading notes

How do you annotate?

Summarize key points in your own words .

- Use headers and words in bold to guide you

- Look for main ideas, arguments, and points of evidence

- Notice how the text organizes itself. Chronological order? Idea trees? Etc.

Circle key concepts and phrases

- What words would it be helpful to look-up at the end?

- What terms show up in lecture? When are different words used for similar concepts? Why?

Write brief comments and questions in the margins

- Be as specific or broad as you would like—use these questions to activate your thinking about the content

- See our handout on reading comprehension tips for some examples

Use abbreviations and symbols

- Try ? when you have a question or something you need to explore further

- Try ! When something is interesting, a connection, or otherwise worthy of note

- Try * For anything that you might use as an example or evidence when you use this information.

- Ask yourself what other system of symbols would make sense to you.

Highlight/underline

- Highlight or underline, but mindfully. Check out our resource on strategic highlighting for tips on when and how to highlight.

Use comment and highlight features built into pdfs, online/digital textbooks, or other apps and browser add-ons

- Are you using a pdf? Explore its highlight, edit, and comment functions to support your annotations

- Some browsers have add-ons or extensions that allow you to annotate web pages or web-based documents

- Does your digital or online textbook come with an annotation feature?

- Can your digital text be imported into a note-taking tool like OneNote, EverNote, or Google Keep? If so, you might be able to annotate texts in those apps

What are the most important takeaways?

- Annotation is about increasing your engagement with a text

- Increased engagement, where you think about and process the material then expand on your learning, is how you achieve mastery in a subject

- As you annotate a text, ask yourself: how would I explain this to a friend?

- Put things in your own words and draw connections to what you know and wonder

The table below demonstrates this process using a geography textbook excerpt (Press 2004):

A common concern about annotating texts: It takes time!

Yes, it can, but that time isn’t lost—it’s invested.

Spending the time to annotate on the front end does two important things:

- It saves you time later when you’re studying. Your annotated notes will help speed up exam prep, because you can review critical concepts quickly and efficiently.

- It increases the likelihood that you will retain the information after the course is completed. This is especially important when you are supplying the building blocks of your mind and future career.

One last tip: Try separating the reading and annotating processes! Quickly read through a section of the text first, then go back and annotate.

Works consulted:

Nist, S., & Holschuh, J. (2000). Active learning: strategies for college success. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. 202-218.

Simpson, M., & Nist, S. (1990). Textbook annotation: An effective and efficient study strategy for college students. Journal of Reading, 34: 122-129.

Press, F. (2004). Understanding earth (4th ed). New York: W.H. Freeman. 208-210.

Make a Gift

Research Strategies

- Reference Resources

- News Articles

- Scholarly Sources

- Search Strategy

- OneSearch Tips

- Evaluating Information

- Revising & Polishing

- Presentations & Media

- MLA 9th Citation Style

- APA 7th Citation Style

- Other Citation Styles

- Citation Managers

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review How to

What is An Annotated Bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is a list of sources (books, articles, websites, etc.) with short paragraph about each source. An annotated bibliography is sometimes a useful step before drafting a research paper, or it can stand alone as an overview of the research available on a topic.

Each source in the annotated bibliography has a citation - the information a reader needs to find the original source, in a consistent format to make that easier. These consistent formats are called citation styles. The most common citation styles are MLA (Modern Language Association) for humanities, and APA (American Psychological Association) for social sciences.

Annotations are about 4 to 6 sentences long (roughly 150 words), and address:

- Main focus or purpose of the work

- Usefulness or relevance to your research topic

- Special features of the work that were unique or helpful

- Background and credibility of the author

- Conclusions or observations reached by the author

- Conclusions or observations reached by you

Annotations versus Abstracts

Many scholarly articles start with an abstract, which is the author's summary of the article to help you decide whether you should read the entire article. This abstract is not the same thing as an annotation. The annotation needs to be in your own words, to explain the relevance of the source to your particular assignment or research question.

Annotated Bibliography video

MLA 9th Annotated Bibliography Examples

Ontiveros, Randy J. In the Spirit of a New People: The Cultural Politics of the Chicano Movement . New York UP, 2014.

This book analyzes the journalism, visual arts, theater, and novels of the Chicano movement from 1960 to the present as articulations of personal and collective values. Chapter 3 grounds the theater of El Teatro Campesino in the labor and immigrant organizing of the period, while Chapter 4 situates Sandra Cisneros’s novel Caramelo in the struggles of Chicana feminists to be heard in the traditional and nationalist elements of the Chicano movement. Ontiveros provides a powerful and illuminating historical context for the literary and political texts of the movement.

Journal article

Alvarez, Nadia, and Jack Mearns. “The Benefits of Writing and Performing in the Spoken Word Poetry Community.” The Arts in Psychotherapy , vol. 41, no. 3, July 2014, pp. 263-268. ScienceDirect , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.03.004 .

Spoken word poetry is distinctive because it is written to be performed out loud, in person, by the poet. The ten poets interviewed by these authors describe “a reciprocal relationship between the audience and the poet” created by that practice of performance. To build community, spoken word poets keep metaphor and diction relatively simple and accessible. Richness is instead built through fragmented stories that coalesce into emotional narratives about personal and community concerns. This understanding of poets’ intentions illuminates their recorded performances.

*Note, citations have a .5 hanging indent and the annotations have a 1 inch indent.

- MLA 9th Sample Annotated Bibliography

APA 7th Annotated Bibliography Examples

Alvarez, N. & Mearns, J. (2014). The benefits of writing and performing in the spoken word poetry community. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41 (3), 263-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.03.004 Prior research has shown narrative writing to help with making meaning out of trauma. This article uses grounded theory to analyze semi-structured interviews with ten spoken word poets. Because spoken word poetry is performed live, it creates personal and community connections that enhance the emotional development and resolution offered by the practice of writing. The findings are limited by the small, nonrandom sample (all the participants were from the same community).

- APA 7th Sample Annotated Bibliography

- << Previous: Citation Managers

- Next: Literature Review How to >>

- Last Updated: Apr 8, 2024 9:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csun.edu/research-strategies

Report ADA Problems with Library Services and Resources

All Neuroscience: Annotated Bibliography

- Find Articles

- Evaluating Sources

- Science Citation This link opens in a new window

- Annotated Bibliography

What is an Annotated Bibliography or a research annotation

What is an Annotated Bibliography (AB)?

An annotated bibliography (AB) is a list of citations (journal articles, books, etc) where each citation is followed by a brief (about 120-150 words) evaluative and descriptive paragraph of the article (i.e. a summary of the research article in your own words). The purpose of annotating is for the reader to get the "gist" of the article by reading this one paragraph . I recommend that in your paragraph(s) [i.e., annotation] you expose the author's point of view , key findings , and show how their work is relevant (e.g., strengthens, has opposing views, complements, provides a new perspective) to your topic. As you build your AB ask yourself: (a) is the article/source adding information to your topic , (b) is it contradicting or confirming ideas you may have read previously about , (c) is it a new source , (d) is the author an authority in the area (e.g., published a lot in good journals)? Asking these questions will help you put together a succint annotated bibliography that will later provide key information to put your presentation together. It will also save you: (a) time , since recalling what the article is about will be easier after reading other papers for your topic, and (b) reduce the chances of word-for-word plagiarism because the summary will be in your words (you will still need an in-text citation though).

In general: summarize , assess and reflect on the work you are reading. By doing this you are engaging in the analysis of the article in meaningful ways- it will pay off later when you put your presentation or article together.

FYI: An annotated bibliography is NOT a copy of the ABSTRACT but it can be seen as your first step towards a REVIEW of THE LITERATURE in your selected topic.

For more details on Annotated Bibliographies check out the resources below.

Cornell: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

Purdue: http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/614/01/ (Direct LINK )

University of Wisconsin: http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/AnnotatedBibliography.html

Literature Review

What is a literature Review? How is this different or the same as a review paper?

A literature review can be: (a) a simple summary of the sources in a narrow topic within a subject area of interest or (b) it can be an organized summary and synthesis of the same topic/subject in the form of a paper. Some literature reviews, if standalone, could become review papers or survey papers. The latter usually relatet papers to one another, present what is the most important things in the field at present and perhaps provides future directions of work in such a field. These papers usually are longer and may have thousands of references associated to them.

Another way of thinking about this is that if the literature review is part of a "thesis or dissertation", it helps provide a context for the research and has less references than an actual review paper. However, if this review is a standalone paper that helps synthesize and summarize information in that particular (subject/field) then we could argue that it is a review paper or survey paper.

What is the Literature Review?

- Literature Review (Part 1)

- Literature Review (Part 2)

- Scientific Primary Sources

Example Annotated Bibliography

- CS Example- Theme: Facial Recognition

- ECON Example: Artificial Intelligence

- << Previous: Science Citation

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 11:28 AM

- URL: https://library.earlham.edu/neuroscience

Earlham College • 801 National Road West • Richmond, Indiana 47374-4095

Annotating a Scientific Paper

- Description

By Karin Akre, Hunter College

Description #

Students annotate a scientific paper in order to help the entire class digest this dense style of writing. They become familiar with the format of these important papers by stopping to annotate words or phrases with definitions, images, connections or questions. By the time everybody has annotated the paper, a student can read through and learn from everyone’s contributions.

Specifically, students are asked to make three annotations: They add two brief clarification aids, such as definitions or images, and one more substantial contribution of making a connection to something they have learned or asking a question about how this point connects to something they have learned. Students are asked to read through the paper twice, once while annotating, and again later to read other students’ annotations.

Reading scientific papers is tough. But once you’ve gotten used to them, they make a lot of sense – they all organize the information according to the scientific method. Annotating as a group should help you get used to things. I’ll be curious to see whether the group annotation articles make more sense to you than the others that we’ll read. Let me know!

Assignment #

Read the article! When you find parts that confuse you, look up what it means or refers to and create an annotation. If someone has already annotated it, click and read the annotation.

To annotate, highlight the text you are annotating, click the dialogue icon, and a sidebar will open up for your annotation. To add images, click on the image icon in the tool bar. Your image will need to have a URL.

NOTE: HIGHLIGHT AS LITTLE AS POSSIBLE. Focus in on the specific word or phrase you want to define or explain. You can annotate a word or phrase within someone else’s highlighted area.

Create two annotations that provide facts (definitions, explanations, etc) or images (maps, animals, etc), and one that adds an insight (connect to another field or another topic) or asks a question.

Ideally the annotations should help you understand the article. It’s tricky because the first people to annotate won’t get as much out of it… So you should do one read early on, and make your annotations at this time. Then, at the end of the week go back to read the article again – it will be much easier with all the annotations! At the very least, studying the article again for tests will be a time you can take advantage of all the annotations.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license

Share This Article :

CSE Scientific Style and Format: Annotated Bibliography

- In-text Citation Examples

- Reference List Examples

- 4 Easy Steps to Referencing

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

What is an Annotated Biblography?

A list of resources such as books, articles, Web sites, and documents. The entries in an annotated bibliography consist of a citation and a short descriptive and evaluative paragraph, which is the annotation. Annotated are used to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy and the choice of resources used by the writer.

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Why can't I just copy the abstract? An abstract describes the the content of the article. Annotations have a descriptive and critial tone. They should relate to the author's point of view and authority of the resource.

How do I Write an Annotation?

The annotation should be concise and provide a brief analysis of the resource.

Locate the item and note the information needed to cite the book, article, Web site or document in the correct style for your subject. You should review the actual resources. Choose the resources that provide a variety of perspective on your topic.

Write a short entry that summarizes the major theme and scope of the work. You should quote one or more passages or quotes that provide an evaluation of the authority of the author, what type of audience the resources is intended for, and compare and contrast the material or with other resources you have included in your annotated bibliography. You should also explain how this resource will be viable to your research topic.

Sample Annotated Bibliography

The following entries are adapted from a bibliography prepared by Susan Grujevski for her paper “How successfully did Natalie Davis interpret the "hidden world of peasant sentiment and aspiration" in Martin Guerre?” The citations follow the style of the examples in Rampolla’s A Pocket Guide to Writing in History. The citations are formated using the Chicago Manual of Style 16th edition.

BOOK Example:

Davis, Natalie Zemon. The Return of Martin Guerre . Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1985.

This narrative is the main focus of my argument. A valuable contribution to the understanding of the Martin Guerre story, with considerable detail and references to ambiguities which create a large number of interesting and innovative approaches to the study of sixteenth-century French peasantry.

JOURNAL ARTICLE Example:

Davis, Natalie Zemon. “On the Lame.” American Historical Review 93, no.3 (1988): 572-603.

In this article, Davis thoroughly defends her interpretation of the Martin Guerre story, outlining the reasoning behind her approaches, and contributing more complexity to her characterizations. This article informed much of my approach to Davis’ interpretation.

Pringle, Helen and Elizabeth W. Prior. “Inventing Martin Guerre: An Interview with Natalie Zemon Davis.” Southern Review 19, no. 3 (1986): 229-241.

Davis makes clear her intentions to depict the story of Martin Guerre as one revealing many ambiguities. A notable element of this interview was the influence on Davis when observing Gerard Depardieu assume his role for the movie. Entertaining to read Davis’ thoughts in the form of an interview, expressed in a simple and direct manner, which assisted my understanding of her approaches to The Return of Martin Guerre.

- << Previous: Plagiarism

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2023 10:26 AM

- URL: https://libguides.stonehill.edu/cse

Annotated Bibliography Guide

- Definition and Formats

- Elements of Annotation

- Sample Annotated Bibliographies

- << Previous: Elements of Annotation

- Next: APA Style >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 1:07 PM

- URL: https://campusguides.lib.utah.edu/bibannotations

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.17(1); 2019 Jan

Annotated primary scientific literature: A pedagogical tool for undergraduate courses

Matthew kararo.

1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, United States of America

2 STEM Transformation Institute, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, United States of America

Melissa McCartney

Annotated primary scientific literature is a teaching and learning resource that provides scaffolding for undergraduate students acculturating to the authentic scientific practice of obtaining and evaluating information through the medium of primary scientific literature. Utilizing annotated primary scientific literature as an integrated pedagogical tool could enable more widespread use of primary scientific literature in undergraduate science classrooms with minimal disruption to existing syllabi. Research is ongoing to determine an optimal implementation protocol, with these preliminary iterations presented here serving as a first look at how students respond to annotated primary scientific literature. The undergraduate biology student participants in our study did not, in general, have an abundance of experience reading primary scientific literature; however, they found the annotations useful, especially for vocabulary and graph interpretation. We present here an implementation protocol for using annotated primary literature in the classroom that minimizes the use of valuable classroom time and requires no additional pedagogical training for instructors.

This Community Page article presents Science in the Classroom (SitC), a tool for undergraduate educators to introduce their students to primary scientific literature. Annotations scaffold the readers so that authentic scientific practices are explained and recognized for their importance in scientific communications.

A major output of public research universities is primary scientific literature, in addition to educating students and conferring degrees. It is imperative for researchers and universities to increase the transparency and outreach of the primary research literature they produce. However, most primary scientific literature remains unknown and/or inaccessible to the public, because it is published in journals targeting academics in the same field and is often placed behind journal paywalls [ 1 ].

Public research universities also have a responsibility to produce scientifically literate graduates [ 2 , 3 ]. Many students graduate without an understanding of scientific practices and an acculturation to interpreting scientific communication, especially primary scientific literature [ 4 , 5 ]. One way to potentially improve scientific literacy overall and develop specific skills, such as interpreting scientific communication, is to incorporate primary scientific literature into the undergraduate curricula and provide pedagogical tools that may help bridge the divide between everyday language and the language used by experts [ 6 – 11 ].

The study of primary scientific literature as a pedagogical tool in undergraduate biology courses has led to innovative approaches. The most well-known of these may be the Consider, Read, Elucidate the hypotheses, Analyze and interpret the data, and Think of the next Experiment (CREATE) method, in which faculty redesign their existing courses around primary scientific literature in order to provide an intensive and comprehensive analysis of primary scientific literature for undergraduates [ 6 , 12 – 14 ]. Although this type of a semester-long innovative elective course provided student benefits, adding an entire course to a degree sequence may prove difficult and by definition, does not impact students that choose not to include them in an already credit-crunched plan of study. This credit-crunch is especially prevalent at institutions such as the one in this study, Florida International University (FIU), where any additional credit hours are charged at out-of-state tuition rates. Therefore, it would benefit biology education, and biology as a field of study, to develop innovative ways to utilize primary scientific literature as a pedagogical tool, ideally with a minimal impact to existing plans of study and time investment from course instructors.

A growing body of research shows that less-intensive interventions using primary scientific literature can be valuable and useful in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education, with the greatest amount of research happening at the undergraduate level. Programs include journal clubs, data and figure exploration, and tutorials on how to read primary scientific literature [ 15 – 17 ]. Assessment tools used to evaluate these interventions are equally as diverse, ranging from rubrics to validated surveys [ 18 , 19 ].

Annotated primary scientific literature

Annotated primary scientific literature is designed to help readers interpret complex science by overlaying additional information on a scientific research article. Preserving the original text and its context is what makes annotated primary scientific research literature unique from other genres that modify or rewrite the original text. This preservation is the key difference between annotated primary scientific literature and adapted primary literature, an approach that takes portions of primary scientific literature and rewrites the original content to turn them into pedagogical tools [ 20 ]. Science in the Classroom (SitC; www.scienceintheclassroom.org ) is a highly developed and sophisticated example of annotated primary scientific literature that we decided has potential for classroom pedagogical use.

SitC, a collection of freely available annotated papers, aims to make primary scientific research literature more accessible to students and educators. The repository of annotated primary scientific literature articles is accessible to educators and searchable by keyword, classified by topics, and grouped in collections. The process of reading and deconstructing scientific literature in undergraduate courses has been shown to result in students potentially gaining an understanding of scientific practices, such as how scientists design their experiments and present their results, essentially allowing students to experience the logic behind drawing conclusions from a set of data [ 6 , 7 , 12 – 14 ].

Annotated primary scientific literature uses the original text of research articles along with a “Learning Lens” overlay, designed to provide students tools to use for interpretation. The “Learning Lens” is used to selectively highlight different parts of the text and is composed of seven headings: Glossary, Previous work, Author's experiments, Conclusions, News and policy links, Connect to learning standards, and References and notes, which are color-coded to match the corresponding text of the research article. For example, an annotated glossary term, when clicked on, will produce a pop-up box containing the definition of the word ( Fig 1 ). Annotations contained within the “Learning Lens” have been designed to be at the reading comprehension level of a first-year undergraduate student, and ongoing evaluation efforts have provided evidence that this goal is being met [ 21 ].

Annotated primary literature as a pedagogical tool

Annotations provide an educational scaffold that could help students become more comfortable with reading scientific papers. We propose annotated primary scientific literature as an example of a resource that can be incorporated into existing courses and provide scaffolding that may help undergraduate students develop skills necessary to read primary scientific literature while requiring a minimal time investment from instructors. Using annotated primary scientific literature as a pedagogical tool not only could potentially help universities develop scientifically literate graduates, but it may also broaden the impact of primary scientific research literature produced by faculty.

The previously mentioned pedagogical tools and curriculum transformations can require a substantial investment of time and effort from the university, faculty, and staff. Therefore, additional tools and opportunities should be considered in order to achieve a wider variety of complementary opportunities for teaching with authentic scientific practices and engaging students in reading primary scientific literature [ 22 ]. We hypothesize that the incorporation of annotated primary scientific literature in the classroom represents one of these opportunities.

In this pilot study, we had a goal of developing an implementation protocol that could incorporate annotated primary scientific literature into undergraduate courses with a minimal time investment for instructors and minimal disruption and alteration to existing courses and plans of study.

Implementation of annotated primary scientific literature

All data were collected in accordance with an approved FIU Institutional Review Board protocol #17–0398 and #17–0105. Our initial attempts to develop an implementation protocol for using annotated primary scientific literature as a pedagogical tool had the educational goal of introducing students to the “Learning Lens” annotations and observing how instructors and students used the tool. Initial attempts to incorporate annotated primary scientific literature focused on undergraduate biology courses at FIU, including General Biology II, Ecology, and Plant Life History. The implementation sessions were run iteratively during the same semester, ensuring that students did not overlap, and each class had only one implementation session. We describe two variations of our implementations here.

Students involved in the study self-reported their major, with 76% being biology majors. We did not collect any data on students’ prior knowledge of biology, but the majority of students in these classes are first- or second-year students.

We used the same annotated piece of primary scientific literature for all in-class activities described in this study: “Caffeine in floral nectar enhances a pollinator's memory of reward” ( https://tinyurl.com/k7m329g ). We chose an article that incorporated many different aspects of biology, including evolution, ecosystem interactions, basic botany, learning and memory, and animal behavior in a single study, making this paper applicable in a wide variety of undergraduate courses.

The objectives were to introduce undergraduate students to annotated primary scientific literature and collect baseline data on how students interacted with the annotations themselves. The first implementation involved a one-time intervention, connected to the student’s coursework, conducted by the researchers and began with an approximately 5-minute orientation to annotated primary scientific literature. This orientation included how to use the “Learning Lens” and a brief overview of the importance of primary scientific literature. Students were then given 20 minutes to read the selected piece of annotated primary scientific literature. At the 20-minute time point, a Qualtrics (online survey software; Provo, Utah and Seattle, Washington) link was provided, and if they were done reading, students could begin answering the feedback questionnaire. Students were given an additional 20 minutes to complete the questionnaire. Collecting and analyzing this first round of pilot data allowed for reflection on opportunities for iterative improvement.

In addition to the questionnaire data, feedback was collected through in-class activity observations conducted by the researchers. We kept detailed field notes indicating when students appeared on task, i.e., independently interacting with annotated primary scientific literature. We also noted when alternative tasks were observed, i.e., students checking email or social media, and when task completion appeared to have occurred. During the implementation, our in-class observations estimated an average time on task, i.e., interacting with annotated primary scientific literature, to be 10 minutes, because there was a noticeable increase in classroom noise after this time point. We confirmed this by using Adobe Analytics (Adobe, San Jose, California), which measures the time spent on a website by each user. We measured an average time spent on annotated primary scientific literature of 13 minutes. Due to limitations of Adobe Analytics, we are unable to collect individual data points and were limited to an aggregate average for the entire class. Note that the difference between the observed time spent on the activity and the digital measure can be explained by Adobe Analytics averaging all participants’ time spent on the article page.

The main student feedback was collected through a questionnaire containing both quantitative (content questions) and qualitative items (i.e., “what did you like about this activity?”). One of the key ideas we garnered from the qualitative data was that a one-time intervention was perceived by students as somewhat discordant when a connection between the article they read and the content they were covering at the time in their course was not made explicit by their course instructor ( Table 1 ).

| Student | Response to item “Did the topic of this paper connect to your course?” |

|---|---|

| Example 1 | No, we[‘re] studying plants. |

| Example 2 | No, only slightly relevant to the course. |

| Example 3 | Not necessarily because this paper was speaking about the effects of drugs on memory. |

| Example 4 | I’m not sure. |

When asked if the topic of the paper related to their course, students in this iteration gave feedback such as this activity was “only slightly relevant to the course,” and “no, we[‘re] studying plants” despite the article being explicitly about caffeine production by plants in order to attract pollinators. Additionally, we were uncertain that we had connected with the students as researchers in the same way as the instructor with whom the students had built a relationship.

Although some students may have not perceived a connection between the article content and their course content, in general, students found the annotations useful, especially regarding graphs and vocabulary interpretation. Examples of student responses can be seen in Table 2 .

| Student | Response to item “What did you like about the annotated paper?” |

|---|---|

| Example 1 | The glossary. |

| Example 2 | Vocab definitions. |

| Example 3 | What I mostly liked about the annotated paper was the part on how the graph had an overview, the nuts and bolts part because it is breaking down the graph for you. |

| Example 4 | I liked the definitions being highlighted and easily defined is needed. I also liked the explanations of the graphs. |

For our second iteration, we decided to address the issues of students feeling discordant by having the course instructors introduce the article and annotated primary scientific literature activity themselves. Additionally, we asked instructors to explicitly connect the annotated paper to current course content. With both of these procedures in place, the average time students engaged with the annotated article, as measured by Adobe Analytics, increased to 19 minutes ( Fig 2 ).

This new implementation, in which the instructor introduced the piece of annotated primary scientific literature and annotated primary scientific literature activity, not only appeared to increase the time that students engaged with the material, but it also removed the manpower requirement for the researchers to be present in every classroom in order to describe and implement the activity. This could allow for a more widespread implementation of annotated primary scientific literature as a pedagogical tool. It was also apparent that students introduced to the activity by their course instructor were more readily able to recognize the connections between reading primary scientific research literature and their course content, which can be seen in student responses in Table 3 .

| Student | Response to item “Did the topic of this paper connect to your course?” |

|---|---|

| Example 1 | This article related to 3 different courses I am taking this semester. |

| Example 2 | Yes it most certainly did. |

| Example 3 | Yes! We’re learning about pollination. |

| Example 4 | …scientific papers on new experiments…are important. |

When asked if the topic of the paper related to their course, students in this iteration stated “This article related to 3 different courses I am taking this semester,” “yes it most certainly did,” “yes! We’re learning about pollination,” and that “…scientific papers on new experiments …are important.”